Photos from Wired for War, courtesy of iRobot.

Peter W. Singer is not your typical “military expert.” At 33 years old, he is the director of the Brookings Institution’s 21st Century Defense Initiative and the youngest senior fellow in the think tank’s 90-year history. In 2003, his book Corporate Warriors chronicled the rise of the privatized military industry; Children at War, released in 2005, examined the tragic phenomenon of child soldiers. He also served as the coordinator of President Barack Obama’s defense policy task force during Obama’s campaign—a role he took on after consulting for The West Wing.

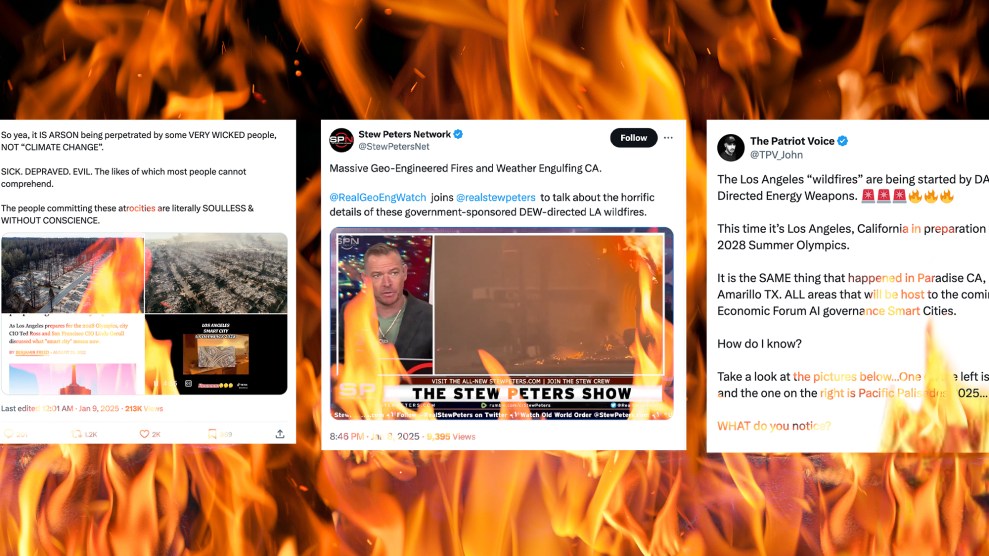

In his new book, Wired for War, Singer takes an in-depth and at times frightening look at the growing use of robotics by the military—a development that he argues will be looked on as “something revolutionary in war, maybe even in human history.” Recently, he spoke with Mother Jones about the unforeseen ripple effects of these new technologies, the folly of calls to use robots in Darfur, and whether we should ban these machines before it’s too late.

Mother Jones: Was there anything in particular that surprised you or scared you as you researched the book?

Peter Singer: I think three parts were most surprising. One was the openness with which people talk about how science fiction influenced what the scientists build and what the military asked to be built. That’s what drew me to research science fiction’s influence on science reality. I was really driven by just how many people would describe some weapon or robot and say, “I was watching this Star Wars movie with my kids and I thought it would be cool if we could have something like that.” And it’d be a Marine colonel saying that. There is also a great scene in the book where the folks at a human rights organization I was visiting are referencing Star Trek more than the Geneva Conventions.

The second part of this is how quickly things moved. In the first draft of the book there were systems on the commercial and military side that didn’t exist then that are out there now. Related, this issue of arming and autonomy of robots is farther along than I thought. Finding some of the studies about “taking man out of the loop” was a little bit surprising and scary.

Finally, the international “blowback” issue was much bigger than I suspected, which became very clear after interviews with folks in the Middle East. I knew, of course, broadly that there were serious issues with our public diplomacy, but how dire it was when it came to our new military technology was a little bit surprising even to me.

MJ: What do you think are the most overlooked negative consequences of developing a more roboticized fighting force?

PS: The part that I find overlooked from the political side is how our greater use of these technologies affects our own understanding of war, especially the public’s links to war. We can walk through a recent example. There was an editorial in the Washington Post this month that talked about how we should do something in Darfur with unmanned machines. Now, let’s leave aside the irony of a humanitarian intervention done by an inhuman machine. What we overlook too often is that military operations are not simply throwaway commitments, even with machines. They involve you in something that is complex and long-term on the ground.

The public’s relationship to their military in the US is a frayed thread right now. We don’t have a draft. We don’t have declarations of wars anymore. We don’t even have presidents asking the public to pay higher taxes. Now add in a situation where Americans are mainly only risking their machines. The bar to war was already lowering. Now you take it all the way to the ground. This was a huge concern of the soldiers I interviewed.

MJ: Also, so many of your interviews showed that the strategic impact of using more robotics on the battlefield is questionable, and that they could even backfire.

PS: It’s tough because you’re dealing with two arguments that make a great deal of sense. The “hearts and minds” element is so important to countering insurgencies, but at the same time the technology has proven to be useful. The limited discussions that we’ve had on robots have always been on absolutist terms. How this is all playing out in reality is way more complicated. And it’s already complicated now with our current Model T Ford versions of robotic technology. Imagine how it will look with the next generation and the generation after that.

In my world of the people who study war and defense issues, we simply did not talk about robotics. We do not talk about it because it’s seen as mere science fiction. Well, guess what? It’s cold, hard, metallic reality. These systems are being used right now whether you like it or not, and they are only the start.

MJ: How are robots going to affect our connection to modern war?

PS: More than just removing humans from risk, these technologies record everything that they see. So they reshape the public’s relationship with war. This has given rise to what soldiers call “war porn.” You get some clip of the UAV [unmanned aerial vehicle] blowing someone up in an email, as if it’s a joke. There are 7,000 video clips of combat footage out there for anyone to download, put to music, etc. There’s no other way to put it. It bastardizes the experience of war. It should really scare us.

That’s why I make the parallel with ESPN and the NBA. It’s one thing to be at the game or even play in the game; it’s another to watch it on TV. It’s even another to see it just via SportsCenter clips like these, which make the experience just a facade of all slam dunks and smart bombs. Then, you have the ultimate nightmare scenario: What if we all don’t even care to watch the clips? What if our relation to war isn’t like the NBA, but the WNBA?

MJ: Having taken on Corporate Warriors, what kind of similarities do you see between the private military industry and robotics?

PS: I actually think that there is a bigger connection than maybe is obvious. By that I don’t mean that Robo-Blackwater is going to be knocking at your door anytime soon. They both challenge our assumptions about war. Corporate Warriors was about the fact that the public’s monopoly of the military has broken down. You have private actors in war that are fighting not as part of state militaries, but private military corporations.

Another assumption about warriors is that they are human. Well, guess what? Machines are increasingly doing the fighting. But even if they are human, the look of that human is being reshaped by technology. Your image is likely of John Wayne storming the beachhead. But it’s also now the guy sitting behind his computer in a cubicle outside of Las Vegas. It’s also the SWORDS system [an armed ground robot that has been deployed to Iraq].

Another theme that connects both books is that we started hiring these guys without thinking about the consequences or creating the proper legal structures to ensure accountability. Well, substitute the word “robot” for “contractor” and the same thing can be said. You are using them more and more but they are creating questions in the legal realm that you don’t have the answers for yet. So you’re jumping into the water without looking first.

Finally, there is the bigger story about the disconnect between the public and their foreign and defense policies. Private military firms are a way of avoiding the cost of going to war. I don’t mean the financial cost, but trying to dodge the public cost. And that’s the same thing with unmanned systems, just in a whole new digitized way, maybe a deeper way.

MJ: How do you see the coverage of this issue in the mainstream media, and why is there not more criticism?

PS: This is the story of humans on every problem. We wait until Pandora’s box is opened before we say, “Wow, maybe we should understand what’s in that box.”

What intrigues me is that there are some things where we are willing to have these discussions of big trends even before they’re fully playing out. For example, we’re finally having a serious discussion about global warming, even though it won’t take full effect until 2030 or 2050.

But for some reason you can’t do that when it comes to defense issues and war. You can’t talk about anything beyond the tip of your nose. The gatekeepers of the field don’t want you to have that kind of discussion.

MJ: What do you make of the SWORDS, which has been praised in the press?

PS: The goal of the book was to be critical in terms of asking the questions that need to be asked. The SWORDS certainly deliver on a lot of things that they were asked to deliver on. You can’t get mad at the company for building this thing. But you need to ask the next question about the ripple effects. What happens next? How is it used, and what are the implications?

I just don’t see us undertaking that kind of critical questioning right now. It’s pretty amazing because I really do believe that we’re going to look back on this period as something revolutionary in war, maybe even in human history. Certainly to the level of the atomic bomb, maybe even greater. And isn’t it insane that we’re not having that discussion right now? Unlike the period of the atomic bomb, it’s happening right in front of us. It’s not happening in some secret lab somewhere.

MJ: Given your role in the Obama campaign, do you have any idea of how he or his national security team is thinking about moving forward with robotics?

PS: In the current defense and economic environment, you are simply not going to be able to buy everything that you want. So that means that you’re going to have to focus on things that meet the needs of soldiers in the field. Now where that relates to unmanned systems is the irony that these are the most high-demand systems right now. For example, we’re meeting only about 5 percent of the soldiers’ demand for drone footage.

While I don’t think you’ll see any kind of international regime on these systems in the hopeful eight years of the Obama administration, I do think we will see an interest in the elements that underscore good policy and good arms control.

MJ: You examine the genre of sci-fi, which often seems to warn of the dangers of the path that we’re currently headed down. What predictions do you think are likely to come to pass?

PS: Sci-fi is often a metaphor. Were the creators of The Matrix saying that one day soon machines are going to run a world like this, or were they making the point that we are already wrapped within a matrix of technology that we depend on every day and we just don’t realize it? I think it’s more the themes and questions that science fiction raises rather than the exact predictions that should guide us.

MJ: You also go over historical examples of what has been done about weapons that we found beyond the pale, and various proposals for what could be done with robotics. What would you like to see happen?

PS: I think the first step is that you have to open the discussion. We can’t just continue to be in denial about these technologies. We know what’s happened with every single previous technology that seemed like science fiction. People said, “Oh no, we’ll never use that in war.” And yet we did. That was true whether you were talking about airplanes and strategic bombing or nuclear weapons. And if you wait until after the fact, it’s a whole different story.

My fear is that that’s what’s going to happen—in fact, I think it’s already in a way happening—with robotics and the military. Importantly, this discussion has to involve not just the scientists, but also the political scientists. It’s got to be a multidisciplinary discussion. You can’t have it be another repeat of what happened with the people working on the atomic bomb. I think the example of what’s happened with genetics research is a great potential guidepost for that. They knew they were working on something that wasn’t just important in the hard sciences but was going to be really important to humanity writ large. And that meant that they better start involving a much wider set of people and wrestling with the issues that came out. It doesn’t mean we somehow solved all of the problems with genetics, but people are working on it.

MJ: What should be the role of international law? Should there be an international treaty to limit or ban their usage?

PS: We may well conclude that there is a need for certain arms control, that there are certain elements of these weapons that we think should not be developed or should not be used in war. Indeed, if history is any guide, there are a lot of weapons that we’ve developed which we’ve pulled back from—biological weapons, chemical weapons, etc. This may be the case with armed autonomous robotics, where we ultimately pull back from them. Or, there may be elements that you say need to be written or built into the system, such as a fail-safe device on any robot, or software to ensure that it follows ethical protocols.

But the biggest thing is that you can’t be in this current mode of denial. History is not going to look kindly on us—if we’re lucky enough to be around a hundred years from now—if we just keep our head in the sand on this issue because it sounds too science fiction.