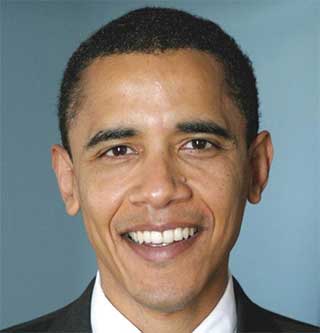

Below is the Barack Obama quote our question refers to (from a February 12 speech). The participants’ answers follow.

Nothing worthwhile in this country has ever happened unless somebody, somewhere is willing to hope. Somebody is willing to stand up. Somebody who is willing to stand up when they are told “No you can’t” and instead they say, “Yes we can.”

That’s how this country was founded. A group of patriots declaring independence against a mighty British empire—nobody gave them a chance—but they said, “Yes we can.” That’s how slaves and abolitionists resisted that wicked system, and how a new president charted a course to ensure we would not remain half slave and half free.

That’s how the greatest generation—my grandfather fighting in Patton’s Army, my grandmother staying at home with a baby and still working on a Bomber assembly line—how that greatest generation overcame Hitler and fascism, and also lifted themselves up out of a Great Depression.

That’s how pioneers went West when people told them it was dangerous, they said, “Yes we can.” That’s how immigrants traveled from distant shores when people said their fates would be uncertain, “Yes we can.” That’s how women won the right to vote, how workers won the right to organize, how young people like you traveled down South to march and sit in and go to jail, and some were beaten and some died for freedom’s cause. That’s what hope is. That’s what hope is.

That’s what hope is. That moment when we shed our fears and our doubts. When we don’t settle for what the cynics tell us we have to accept. Because cynicism is a sorry sort of wisdom. When we instead join arm in arm and decide we are going to remake this country, block by block, precinct by precinct, county by county, state by state. That’s what hope is.

There’s a moment in the life of every generation, when that spirit has to come through if we are to make our mark on history. And this is our moment. This is our time.

Jabari Asim

Editor of The Crisis magazine

Talcott Garland, the introspective narrator of Stephen Carter’s novel The Emperor of Ocean Park, describes another character as “a type common to the darker nation: smart, ambitious, well educated, utterly dedicated to the romanticism of the long-shattered civil rights movement, living on the fringes of what remains.” It’s a harsh assessment, to be sure, but eloquently points to a sort of misbegotten nostalgia that occasionally threatens to overwhelm the movement’s valuable lessons, a sensibility apparently found most often among elders of the African American community—those actually old enough to remember those bloody, world-changing battles or to still bear scars from being a frontline participant.

Those of us in Obama’s generation are left to tiptoe gently among these veterans, paying tribute to them without appearing to ride lazily on their coattails, offering sober assessments of the movement’s triumphs and shortcomings without seeming ungrateful or disrespectful. Obama continues to walk that fine line with the skill and diplomacy that has defined his political career thus far and, in reasonably describing his campaign as a logical extension of the civil rights movement, continues to maintain admirable balance. It’s hard to imagine a perspective that doesn’t regard his pursuit of the presidency as the fruitful harvest of seeds sown in those marches, sit-ins, legal challenges, and strategic campaigns of not so long ago.

Jennifer Baumgardner

Author, Look Both Ways: Bisexual Politics

Barack Obama is saying “Yes we can…support a biracial (Ivy-educated, male, lawyer) candidate for the highest office in the nation,” which shouldn’t be confused with “Yes we can…wage a social justice revolution in which everybody has health care, the death penalty is considered an abomination, and we won’t bomb Pakistan.”

Symbolically, I find it inspiring to have someone raised by a teen single mom in a blended family, who isn’t white, who admits to drug use on his journey to becoming the responsible father he is now as my potential president. But Obama’s campaign is quite clearly not a social justice movement. What is he abolishing? Who is he freeing? What goal of citizenship is on the line with him as its champion? What is he risking by taking a stand? What “stand” is he taking?

Any viable candidate for President—and whether he wins or not, Barack Obama is clearly viable—isn’t waging a revolution for peace, truth, and justice when he runs. He is relentlessly calibrating complicated positions about even more complex issues and balancing as carefully as possible on messages of change that aren’t, in fact, too changey. I don’t find this realpolitik disturbing, but I find the message of “hope” he conveys empty and even besides the point, especially as he proves in the general election to have exactly Hillary Clinton’s positions. Fortunately, having Clinton’s positions isn’t a bad thing for the country. It may not be a movement, but Obama’s campaign is at the very least movement—toward a commitment to the middle class, better health care options, and an incredibly reasonable and thoughtful man in the White House.

Pat Buchanan

Columnist

It is absurd to argue that the nomination or an election of Barack Obama would be as important a historical event as the liberation of 3 million slaves after the bloodiest war in American history, that took 600,000 lives and set the South back a century. As for the civil rights movement, that completed the emancipation of people of color, and has dramatically affected American politics for a half-century. Barack Obama’s election would be about as significant to US history as Jackie Robinson’s appearance at second base was for the Brooklyn Dodgers. Yet that, according to liberals, was the most important event in the history of baseball. This whole exercise testifies to what Lenin called “an infantile disorder” of the American left. Give it a rest.

Eleanor Clift

Author, Founding Sisters and the 19th Amendment

Better left to others to make the comparison, but I think it’s valid. We have to ask ourselves how reform is made. It takes acts of courage by countless unsung people to collectively create the conditions for a leader to take hold. Cultural change of this magnitude doesn’t occur until millions of people come to a consensus that it is needed, and it’s not about race or ethnicity. The excesses of the last eight years have brought us to the point where the voters have had enough.

Howard Dean tapped into the same wellspring of fury in 2004, but wasn’t able to translate Internet money into political activity. Using the power of Barack Obama’s persona and personal history, his campaign created a community of people with the energy and the power to affect elections. Obama has taken back the electoral process from the big-money interests and returned it to the people. He doesn’t treat his donors like an ATM; he makes them feel they are part of something bigger than themselves. With the power of the people a computer click away, Obama is on track if he wins the presidency to restore the balance between the demands of the special interests and the needs of the people. By my lights, that’s the definition of a movement in the great progressive tradition.

Ta-Nehisi Coates

Author, The Beautiful Struggle: A Father, Two Sons, and an Unlikely Road to Manhood

Well, I think he’s exaggerating, in the sense that it’s hard to understand a great, substantive moment in history while it’s still happening. We knew 9/11 was a historic moment, if only because nothing like that had ever happened. But we didn’t know—and maybe still don’t completely know—what that actually meant. So in the sense that all people who compare the ongoing, shifting, malleable present with the past, he is indeed exaggerating. Let me just state the obvious—electing a black president will be historic, and I guess quasi-progressive. But the substance of what his presidency will be for America just isn’t known yet.

Folding on FISA certainly doesn’t put you in a great progressive tradition. But pushing efforts to ameliorate the wealth gap might. It’s really up to Obama to determine whether or not he’s exaggerating. He is a politician, and thus prone to political rhetoric. I say that as one of his supporters, and charges of Kool-Aid imbibing aside, I think most of us know that too. If Obama goes forth and really reorients the country away from anti-intellectualism, fake patriotism, and craven powermongering toward a path of honest debate, muscular patriotism, and simple common sense, then he will be right in claiming the best of the progressive tradition. If not then it’ll just be rhetoric. It’s really up to him.

Robert Dallek

Author, Nixon and Kissinger: Partners in Power

I find the question impossible to answer. How can we possibly know at this point what Obama’s campaign means? Is it the equivalent of some of the great progressive events of the past you cite? To answer would be to get way ahead of ourselves. First he has to win, and then we will see what he accomplishes. I certainly hope he is successful, but I don’t want to predict what his achievements will be.

Debra Dickerson

Author, The End of Blackness

Kudos to Obama for reaching transcendence, but no way is the undeniable excitement he’s generated anything remotely resembling America’s past great progressive movements. To point out the obvious, the very examples he’s invoking had specific purposes—winning World War II, ending slavery then Jim Crow, enfranchising women. Beyond dethroning Bush II, worthy though it is, what’s his goal? Even were he to peg his entire candidacy on ending the Iraq War, that wouldn’t transform America the way past convulsive movements did. At best, electing Obama might be seen as the final death throes of a racism that still dares to speak its name, but it might just be best if he stopped playing to his fellow citizens’ lazy vanity—look, Ma! I’m changing America without sacrificing anything in the least!—and kept what he represents in perspective. His nearness to the presidency is an amazing, wondrous thing, but America won’t be much different afterward, blasphemous as that sounds.

Harold Evans

Author, The American Century

The great progressive movements in American history, not excluding the populists, all had specific programs to deal with definable evils and restrictions, all to make America more of a functioning democracy, truer to the ideals in the Declaration of Independence rather than the rule of the elites envisaged by the founding fathers. One thinks of the clear programs set out by William Jennings Bryan—and hooted down—for federal income tax, direct election of senators, regulation of the railroads, and importantly, release from the deflations inevitable when the currency was based on gold. Obama has rhetoric to match Bryan’s, but while the statements are gratifying, even glorious, they are not all well-enough defined yet to constitute anything comparable to the great progressive movements that gave us our present.

John Judis

Journalist

I think Obama has run a brilliant campaign, but not necessarily a “great progressive” one. Purely in policy terms, he is running a center-left campaign similar, say, to Jimmy Carter in 1976 and far less bold than, say, Bill Clinton in 1992. All the stuff about reforming Washington is very much in the line of Carter-John Anderson-Ross Perot. His main economic plans were slightly to the right of John Edwards and Hillary Clinton, and his foreign policy (except for his biographical claim to have been against the war in 2002) was indistinguishable from those of other Democrats. His is certainly not a path-breaking campaign like that of Theodore Roosevelt in 1912 or Franklin Roosevelt in 1936.

But that’s not to say his campaign isn’t significant or important. First of all, he is the first major-party African American candidate. That’s no small thing in a country long divided by race, but his running will not have the same kind of impact as the civil rights movement of the ’50s, which successfully attacked the structure of racial discrimination. Second, he has accelerated trends toward a Democratic realignment that began earlier. He has been particularly successful in bringing young people and professionals into the fold, and in advancing the cyber technology of political campaigns, including the use of the Internet for fundraising, which began, I think, under Perot in 1996, and was then used to advantage by Howard Dean in 2004. So it is a very significant campaign. I just wouldn’t go overboard about its being a “great progressive” one.

Michael Kazin

Author, A Godly Hero: The Life of William Jennings Bryan

To state the obvious: A presidential campaign is not a social movement; its objective is to elect an individual, not to win rights or power or cultural influence for a large group of people who have a set of deep-seated grievances. But Obama’s campaign and the success he’s achieved, so far, does depend on the size, ardor, and creativity of the progressive movement that has been growing since the 2000 election.

That connection between movement and candidate is essential to achieving any meaningful degree of social and political change. But one shouldn’t fall for the illusion that the politician (or any single leader) can substitute for the movement. Neither can accomplish great things alone. But the alliance is nearly always a contentious one—witness the relationship between FDR and organized labor or LBJ and the black freedom movement. Obama’s current attempt to shed his image as a gun-controlling opponent of capital punishment is just the latest demonstration that even the most admirable politicians are captives of the majorities they need to win. They move when movements move them.

Michael Kinsley

Columnist

Of course he’s exaggerating. That is not a crime. In fact, it’s almost required in a presidential candidate. If you don’t have some grandiose historical moment in your pocket, you get nailed as Ted Kennedy famously did for lacking “vision.” But all of Obama’s examples in the passage you quote involve one overwhelming and crystalline issue. There is no such one issue at stake in this election, or if there is, Obama has not articulated it. Abolition, women’s suffrage, and civil rights were all movements that started outside of conventional politics and had built up considerable momentum before being taken up by a president or presidential candidate.

There is a good case to be made that various issues are actually related and together they do make this a watershed election. The common thread is digesting the huge events of the last part of the 20th century, which have turned out to be mixed blessings—or possibly, to Mother Jones readers, neither mixed nor blessings. The end of the Cold War was supposed to have left us a “unipolar” world where the United States faced no threats to its power, and the spread of democracy and capitalism would be inevitable. Instead, we are struggling to figure out our role in a world where we matter less and less. The bill is coming due for a generation of staggering fiscal irresponsibility——mostly attributable to Republican public officials, but the American people have been their enablers. The second industrial revolution, which has brought us computers and miracle drugs, has also apparently ended the era when “a rising tide lifts all boats.” That delinking of prosperity and equality will make us a different kind of country, and we have no idea what, if anything, to do about that. And meanwhile yet another bill is finally coming due for the first industrial revolution, in the form of global warming, the energy shortage, and so on, —even as that revolution spreads to new parts of the world.

As a “world man,” who has excited and inspired people all over the globe without actually doing anything yet, Obama has the potential to weave these issues together and prepare people for the “change” they think they want—much of which they won’t like when they see it close-up. The test of a leader is whether he or she can lead people somewhere they don’t want to go. Whether Obama can do that, or even wants to, remains unclear. In short, whether this is an important historical moment or just another election is up to Barack Obama.

Naomi Klein

Author, The Shock Doctrine

What all transformative movements have in common is the quality of speaking up to an aspirational public, to our best possible selves. Transformative movements act like the world is better than it is, and—when they work—they inspire the world to live up to this partial projection. The Obama campaign, has, in moments, embodied precisely that quality: Obama conjures a better America and that better America shows up for him. But political moments do more than speak to our best selves; they harness that quasi-mystical power to make radical demands to transform the real world. The Obama campaign has not done this, not on any issue at the core of our current crisis. Not on global warming, the war in Iraq, the housing crisis, health care, underemployment, or the assaults on civil liberties. Not a single Obama policy is unequivocal in its clarity and morality, which is the essential quality of a transformative movement.

The campaign’s most radical demand, even if unstated, is the idea of electing Obama himself. It is Obama—and not his plans for the presidency—that is the ultimate expression of the “movement.” If the process ends there, the Obama campaign becomes less like the civil rights movement and more like the lifestyle brands in the late ’90s—the Nikes, Microsofts, and Starbucks that expertly captured the transcendent quality of past liberation movements, and our desire for meaning in our lives, to build their brands.

Of course the real fault is not Obama’s, but ours. We have forgotten the kind of risk and work it takes to build transformative mass movements, and so settle for iconography instead. That said, he’d better win.

Michael Lind

Fellow, New American Foundation

This is indeed a historic moment in American political history. The conservative era that began with Nixon has ended with George W. Bush, and the new era in public policy, as distinct from electoral politics, has already begun. The next reform era is more likely to emphasize common concerns, public efforts, and the national good, like the progressive era and the New Deal era, than individual emancipation, like the abolition, suffrage, and civil rights movements, whose gains are now secure. While his campaign did not create the next-era wave, Sen. Obama has proven his skills in besting his rival surfers on the Democratic team. Whether or not Obama rides the wave to victory in November, the tsunami will proceed, and the reactionary right will be no more able to reverse its course than King Canute was able to command the tide to retreat.

Glenn Loury

Professor of economics, Brown University

Is Barack Hussein Obama a transformative American leader on questions of race? Not when compared to Lyndon Baines Johnson.

A shocking degree of historical amnesia/ignorance has been revealed in the gushing press commentary on Obama’s “race” speech. It seems to me that people are confusing something that is akin to a cult of personality with an actual political movement that is informed by a comprehensive ideological vision and that is capable of making lasting institutional reforms. Obama’s address given in Philadelphia last March—in the aftermath of the initial firestorm created by the public exposure of some of Rev. Jeremiah Wright’s more controversial remarks—has been called the greatest public oration on the question of race since Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech, given at the 1963 march on Washington. This claim is, I think, demonstrably false.

I offer as counterexample to this claim LBJ’s speech given as a commencement address at Howard University in 1965. These two instances of public rhetoric were motivated by very different forces: Obama’s was given under duress, in the midst of a primary campaign, in an effort to control the damage to his electoral prospects from his association with Rev. Wright. LBJ, by contrast, was speaking as a sitting president, articulating a guiding vision that would inform those aspects of his legislative agenda, the war on poverty, that dealt with racial themes. But this is precisely my point. Unlike Obama, LBJ staked out a political position that has had consequences: That the people of the United States were obligated to undertake a massive expansion of social investment for the disadvantaged in American society, and that this obligation rested at least in part on the historical necessity that we act so as to reduce racial inequality in our country. Obama sometimes gives the impression that the less said about our mutual obligation as Americans to act so as to reduce inequality of social outcomes between the races in the country, in the jails as well as the schools, the better. And yet, it was LBJ’s rhetoric, coupled with a focused legislative agenda and the political acumen/muscle to get it enacted, that really constitutes the stuff of historical transformation. And the success of Johnson’s efforts, while limited, to be sure, nevertheless represents the kind of thing that can be accomplished when the apparatus of a political party is harnessed with an ideological vision that has teeth, and that is willing to take a stand on the great questions about the role of government and about the moral imperatives of our imperfect history. What LBJ had to say in that late-spring afternoon, 43 years ago—about race, history, policy, and social obligation—has echoed down through the decades. It was a piece of his war on poverty, with the establishment of federal aid to education and federally financed health care for the poor and the elderly, and with those legislative capstones of the civil rights revolution that LBJ, but not JFK, was able to get enacted.

Of course, nobody can expect Obama to argue for a return of the Great Society. Still, his speech—and more broadly his views about race and American social obligation, whatever their merits—are not in the same league with LBJ’s, not even close.

Will Obama’s effective renegotiation of America’s implicit racial contract redound to the long-term benefit of African American people? Not necessarily, especially to the extent that it lets the American mainstream off the hook in terms of their responsibilities to narrow the racial gap.

Barack Obama, in this campaign, is engaged in a de facto renegotiation of the implicit American racial contract. What, one may ask, might that implicit racial contract be? Well, in a word, it is the broad recognition and acceptance by governing elites in this country—in the press, in the courts and legal establishment, in the academy and in the broader political culture—that structural impediments exist to the equal participation of blacks in American life, and that government-sponsored initiatives—whether race-specific or universal in character—are an appropriate vehicle for redress in this situation. It is the recognition that, despite the huge social transformation occurring in this society under the pressures of immigration, globalization, and rising economic insecurity—which are, as Obama points out, changes affecting all of us, regardless of race or ethnicity—despite this new reality, we nevertheless have unfinished business here on the race front. It is the willingness to constantly interrogate our institutions as to whether their actual practice is consistent with our professed ideals concerning equality and social justice. It is an acknowledgement that, imperatives of personal and communal responsibility notwithstanding, the American nation-state nevertheless bears a collective, political responsibility for the social disasters and the human suffering that are unfolding even as we speak, and that can be so readily observed in the centers of our cities. This responsibility extends to immigrants who have joined our society in recent decades no less so than to those with American ancestry extending back many generations. Just as present generations—immigrants and natives alike—are obligated to service a national debt incurred by their predecessors, so too are those who prosper within our social order obligated to contribute to the fair resolution of social problems deeply rooted in the nation’s historical experience. This unfinished racial business, I would argue, is a part of what you inherit when you become an American.

While there has never been unanimity on these matters, there nevertheless has been a consensus view—a view, I might add, that was recently reaffirmed by a relatively conservative US Supreme Court in the University of Michigan affirmative action cases. This consensus has been under attack for a generation, and now it is, in effect, being renegotiated by Barack Obama in this political campaign. Look for him to throw affirmative action under the bus by advocating that we transition to a scheme based on class and not race come September. Some may object that Obama’s campaign rhetoric and speeches clearly reveal his appreciation of the structural bases for racial inequality. They will say that his view is nuanced, pragmatic, and historically well informed. This all may be true, but the question that matters is not whether Barack Obama knows anything about history or sociology. The critical question is, What are the American people prepared to do next, if anything, about these matters? And how will Obama’s purportedly transformative vision of American politics promote progress?

The answers to these questions are far from clear. What we are witnessing in this campaign is, in effect, that Obama’s very person has been taken by many Americans to be a site for public expiation of collective racial sin! I fully understand why many Americans would leap at the chance for such cheap grace. Still, I fail to see why serious advocates of the interests of black people must fall into the same swoon. Here’s my bottom line: Obama’s authenticity as a representative of the black experience before the American public, even at this late date, is not self-evident—far from it. Saying this does not make me some kind of racemongering black radical. This is not even a criticism of him. It is merely a statement of fact. Nor is it an imputation to him of any invidious motives. Sure, he is ambitious. And yes, he is a politician, doing what politicians must do to get themselves elected. But this issue—concerning what consequences will ensue from the heated discourses of this campaign, for the American civic obligation to pursue greater racial equality in the decades and generations to come—this is a vitally important matter for reflection and discussion.

These concerns are not merely the whining of an older generation that is unwilling to accept that things have changed. If “change” in our racial sensibilities means accommodating the weariness of many Americans with our long, historic, and still unfinished pursuit of racial justice, then I have no trouble standing athwart such progress. Nor am I here blaming Obama for the fact that formulations and arguments that may be forced upon him, by the political logic of his quest for the presidency, can nevertheless have deleterious consequences for black people in this country. Neither do I hold that he, or any other single person, speaks for all of black America. Nevertheless, none of this obviates the fact that pronouncements by prominent persons who are received, de facto, as representatives of a group can enter into the public vernacular, become part of our unexamined political vocabulary, shape how people understand and respond to the social reality within which we are embedded, and in this manner reverberate so as deleteriously to affect other group members.

Clarence Page

Columnist

So far Obama has not spelled out a progressive platform that compares to the earth-moving ideologies of great progressive movement. Lately he’s been backpedaling away from the left and back toward the wobbly middle to expand his support among independent swing voters. Nevertheless, as an African American old enough to have drunk from “colored” water fountains in the South, I am convinced that the election of a progressively minded black—or, if you prefer, biracial—president will mark the capstone of what the civil rights movement was all about. Whether Obama wins or not, he already has changed our national mindset about racial possibilities, revitalized the image and energy of liberal politics, and improved our nation’s image around the world. That’s not small potatoes.

Chris Rabb

Blogger, Afro-Netizen

Obama’s candidacy is not a movement, no matter how historic and unique it may be. It is a fascinating and noteworthy social phenomenon, which is not the same as a movement.

Movements do not revolve around individuals nor elections. Obama is conflating his once-insurgent campaign’s hope to clinch the Democratic nomination and the presidency with the type of movement building it will take to forge meaningful social change in society at large.

From Wall Street to Silicon Valley, from the Beltway to Hollywood, from the military industrial complex to the political industrial complex, structural change will not likely occur.

The tone, tenor, and nuance of discussions around important, but somewhat controversial, topics may change. Rhetoric around such topics may change—even improve. But there is little hope of impacting the foundation of structural inequality. The cynicism of this critique is not necessarily based on my judgment of Obama’s candidacy or his agenda; rather, it is based on the reality that social movements are not predicated on election cycles or politicians, but on broad swaths of a given generation to radically alter some aspect of society as we know it.

Nothing radical will come from either major party in the modern electoral landscape irrespective of the unconventionality of a given candidate.

Rick Shenkman

Editor of History News Network and author, Just How Stupid Are We?

In time-honored fashion, I’ll answer this question with a question. My question is: What was the lesson of the civil rights movement? Was it that you can appeal to the conscience of America? That you have to mobilize activists by high-minded appeals to a cause? That you have to fight like hell for your rights because people in power do not make concessions just because you ask for them politely? That a leader can inspire people to action? Or that it helps immensely to have an archenemy, like Bull Connor?

My answer is: All of the above. Barack Obama comes across like a civil rights movement leader. His rhetoric inspires people the way Dr. King did. But he seems to be selective in his reading of the movement’s lessons. He seems to believe that appeals to reason are ALL that is necessary. The civil rights movement demonstrated that change also requires a good old-fashioned enemy who can be easily ridiculed, hardball tactics, and the willingness to exert pressure on the weak points of the people in power who are blocking change. Politics is not a tea party.

Roger Wilkins

Professor of history, George Mason University

William Faulkner once observed, “The past is never dead; it’s not even past.” In judging Obama’s prediction, I pair Faulkner with a recent note from a brilliant young black man who wrote after viewing friendship circles on the Internet, “What struck me was how few blacks are in the networks of the young professional types…even Democrats and progressive types…we still have a long way before the fundamental sociocultural segregation of our society is relieved.”

I’m old enough to remember how those barriers cracked some when in the late ’30s Joe Louis knocked out the German champion Max Schmeling in the first round. And I remember how a decade later Jackie Robinson’s pioneering performance on the Brooklyn Dodgers cracked them even more.

If two superb black athletes could significantly lessen the “sociocultural segregation of our society,” a superb black president could significantly lessen even more the hold the past has on us, and that presidency would forever be regarded as one of the brightest lights in our national life.

Patricia Williams

Professor of law, Columbia University

Years ago a Vietnamese friend whose parents had sent her to boarding school in India to escape the war spoke to me of her amazement at the then-still-emergent intertwining of Gandhi’s and Martin Luther King’s philosophies. From her vantage point, the most remarkable thing about what became the American civil rights movement of the 1960s was that it was a revolution based on love. “How counterintuitive is that?” she asked. “How many times in history has that happened?”

It’s not that the struggle wasn’t attended by its quantum of brutality and violent backlash, she mused, but rather that King framed his goal as uniting a “beloved community” rather than bringing down a common enemy. It was a battle for recognition of the humanity that resided within every heart, “even Bull Connor’s.”

I don’t think it is at all an exaggeration to say that Barack Obama’s campaign is rooted in and furthers that kind of embracing progressive American story. The Bush administration has brought us to a very dangerous precipice: The world has been divided into good guys and bad guys, the due process promised in the Bill of Rights has been all but suspended by executive whimsy, and the use of torture has gained a stature in American discourse that it has not had since the good old days of public lynchings. Yet for a dangerous few years, public opposition was nonexistent in the face of manipulations like “you’re with us or against us.” Color-coded fearmongering silenced some of us; cynicism and a feeling of helplessness paralyzed others.

Barack Obama has done more to cut through the Orwellian garble of that frozen moment than any other public figure. He has given eloquent voice to the widespread unease at the course our government has pursued; he has done so with grace, without anger. And he has brought enough reasoned good sense back to the discussion that “diplomacy” is no longer a curse word.

If we are to pull back from the cliff’s edge to which George W. Bush has shepherded us, I think it will be because the most redemptive moments in American history have always been rooted in the deepest promise of the First Amendment. I mean not merely the reductive right of frat boys to yell epithets, but the profound commitment to the propagation of ideas about how we constitute ourselves as a nation; the profound power of imagined political possibility; the profound freedom to exchange thoughts without fear of punishment. From the Puritan jeremiads to the Gettysburg address, from Harriet Tubman to FDR’s fireside chats, from Abigail Adams to “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” our most interesting social transformations have always been given life by our most intelligent rhetoricians. Within that tradition, Barack Obama could be our Nelson Mandela—not a magician, but the page-turner to a more encompassing future for all.

Garry Wills

Author, What the Gospels Meant

It is true that Obama is facing a task of historic scale and difficulty, but he has not sufficiently identified it. The task is to restore a Constitution shredded by secrecy, illegal detention, and torture. The real question is whether he can convince the American people that these atrocities must be wiped out—and he has not begun to do that.