Bruce E. Ivins, an anthrax scientist at the U.S. Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases (USAMRIID) at Fort Detrick, died Tuesday at a hospital in Frederick, Maryland, after ingesting a massive dose of prescription Tylenol mixed with codeine. He was 62. According to the Los Angeles Times, he was among the nation’s leading experts on the military uses of anthrax. A native of Lebanon, Ohio, Ivins received his doctorate in microbiology from the University of Cincinatti, had worked in the Fort Detrick laboratory for 18 years, and, in 2003, was honored with the Pentagon’s highest civilian award for resolving technical problems afflicting the Army’s anthrax vaccine. He sat on USAMRIID’s protocol and animal rights committees. He lived in a small white house near the laboratory with his wife. And on Sundays, he played keyboards at his church. He also, according to the FBI, is the man responsible for the anthrax attacks of 2001.

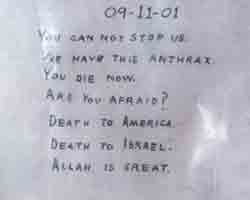

Ivins’ apparent suicide occurred after he learned that the Department of Justice was preparing to file criminal charges against him for mailing a series of anthrax-laden letters in fall of 2001 that killed five people, sickened another 17, interrupted mail service, and shut down a contaminated Senate building for several months.

The anthrax investigation—dubbed “the largest and most complex” in FBI history, according to a spokesman—had become an embarrassment to the Bureau. For years it focused on Steven Hatfill, a onetime USAMRIID colleague of Ivins’, named a “person of interest” by then-Attorney General John Ashcroft in 2002. In June, the Justice Department settled with Hatfill for $5.82 million. (Hatfill continues to press libel cases against the International Herald Tribune, the New York Times, and columnist Nicholas Kristof. He has already reached private settlements with Vanity Fair and Reader’s Digest for their coverage of the case.) Amid speculation that all the attention paid to Hatfill and the alleged mishandling of evidence had caused the investigation to go cold, FBI Director Robert Mueller told CNN last week that “in some sense, there have been breakthroughs” in the case. “I tell you we made great progress in the investigation, and it’s in no way dormant,” he continued.

In September 2006, having little to show for its efforts, the FBI replaced its lead investigator and, concluding that the strain of anthrax used in the attacks was not as sophisticated as first thought, broadened the search beyond Hatfill. The initial suspicion that the letters could only have come from a scientist expert in the production of military-grade anthrax, a field of about 30 individuals, seemed in doubt as agents looked farther afield for suspects. By last spring, however, it appeared that investigators had rounded a corner back to where they began. In March, FOX News reported that the Bureau was focusing on four suspects, among them “three scientists—a former deputy commander, a leading anthrax scientist and a microbiologist—linked to the research facility, known as USAMRIID.”

Ivins had been cooperating with the FBI investigation for about a year, his lawyer, Paul F. Kemp, told the Associated Press. The Bureau’s interest was raised by the revelation that Ivins had failed to report several anthrax contaminations at the Fort Detrick laboratory in the five months immediately following the 2001 attacks. Ivins wiped down several parts of the laboratory with bleach to kill errant anthrax spores, believing, he later told investigators, that samples sent there for testing had been improperly contained. (Ivins was among the scientists involved with testing anthrax samples obtained from letters sent to the Senate.) “In retrospect, although my concern for biosafety was honest and my desire to refrain from crying ‘Wolf!’ . . . was sincere, I should have notified my supervisor ahead of time of my worries about a possible breach in biocontainment,” Ivins explained to Army investigators. “I thought that quietly and diligently cleaning the dirty desk area would both eliminate any possible [anthrax] contamination as well as prevent unintended anxiety at the institute.” The Army elected not to press charges. (Read the results of its official investigation here.)

According to people familiar with the incident who spoke to the Los Angeles Times, Ivins acknowledged swabbing areas in and adjacent to his office for anthrax and applied bleach to kill spores, but was uncertain if he ever reswabbed to ensure there was no further contamination—an obvious and essential step in anthrax containment. A USAMRIID official told the Times that “Ivins might have hedged regarding reswabbing out of fear that investigators would find more of the spores inside or near his office.”

Still, despite suspicions raised by the incident and the Justice Department’s subsequent decision to charge Ivins as the anthrax attacker, the nature of the evidence against him in the case has not been disclosed. The Justice Department will decide in the next few days whether to close the anthrax investigation, but has yet to do so, leaving open the possibility that Ivins did not act alone. There has been speculation that one possible motive for anthrax attacks, assuming they were committed by a government scientist, might have been to win greater funding for anthrax-related research. And according to the Associated Press, the Justice Department planned to charge Ivins with mailing the anthrax letters in order to test anthrax drugs he had been developing.

Also possible, of course, is that Ivins—like Hatfill—is the wrong guy. His suicide comes at a curious moment in the investigation, but Ivins, according to those who knew him, had been suffering from severe depression for many months and had even checked into a treatment clinic last month, partially as a result of the strain placed on him by the attention he had been receiving from federal investigators. Kemp, his lawyer, issued a statement today, denying his client’s involvement in anything sinister. “We are saddened by his death, and disappointed that we will not have the opportunity to defend his good name and reputation in a court of law,” he said. “We assert his innocence in these killings, and would have established that at trial.”

UPDATE 1: New evidence paints Ivins as a bit more than a sensitive biodefense researcher who flew into a depression at being suspected of horrible crimes. According to documents obtained by The Smoking Gun, Ivins’ psychological counselor, Jean Duley of Comprehensive Counseling Associates, filed a restraining order against Ivins last week, claiming he has “a history dating to his graduate days of homicidal threats, actions, plans, threats & actions towards therapist.” The restraining order, granted by a judge, resulted from several threatening phone calls Ivins made last month. Duley writes in one of the documents that she had been scheduled to testify today before a federal grand jury in Washington, DC, with regard to Ivins’ involvement in five capital murders. She further notes that his psychiatrist described him as “homicidal, sociopathic with clear intentions.”

UPDATE 2: Rep. Rush Holt, Jr. represents New Jersey’s 12th District, from which one of the anthrax letters was mailed in 2001. He’s a physicist and the former assistant director of the Princeton Plasma Physics Laboratory at Princeton University, the state’s largest energy research facility. He’s also a longtime critic of the FBI’s handling of the anthrax case. (Read this response from the FBI to a critical letter it received from Holt in 2006.) When the FBI settled with Hatfill in June, Holt stated that he planned to press FBI Director Mueller to release more information on the investigation. I spoke with Holt this afternoon to get his reactions to the day’s news and ask his thoughts about the FBI investigation. Some excerpts:

MJ: What do you think of today’s revelations?

RH: However final this tragic turn is, whether or not it means that the case is closed, it doesn’t change the fact that the investigation was not handled well and shouldn’t have taken six years.

MJ: What went wrong with the FBI investigation?

RH: I watched the investigators take evidence. I’ve used the word sloppy before, and I’ll use it again. They found anthrax in my office. They wiped the entire office with a couple of different wipes and they found anthrax. You’d think what they would do in a case like that is come back and check each inbox to see if you find anthrax there, so that there would be some way of tracing back how the anthrax entered the office. Similarly, once they knew there was anthrax at the Hamilton, New Jersey, mail sorting facility, you’d think they would trace back and find out exactly how the mail entered there. Well, seven months later, they found anthrax in a mailbox on Nassau Street in Princeton. I don’t know what took them seven months to check that. They should have checked it the next day! And then it was reported in the newspaper that agents were on Nassau Street in Princeton the following summer asking if anybody remembered any unusual activity around that mailbox the previous fall.

MJ: Was the FBI forthcoming with you about where things stood?

RH: No, no, certainly not forthcoming. They did brief members of Congress, including me, early on in some detail. They claim there were leaks. If there were, I know nothing about it. And then they just clammed up. It seemed to me that they clammed up, wouldn’t brief us, when it was apparent that the investigation wasn’t going well. Now, I don’t know whether that was why they refused to brief us, but it didn’t inspire confidence.