Photo: Victor J. Blue/Koppel on Discovery

Update: On May 23, 2011, the US Supreme Court ruled that conditions in California’s prisons violated the constitutional ban on “cruel and unusual punishment” and affirmed a lower court’s order that the state drastically reduce its inmate population. This article, published in 2008, provides a detailed look at the Golden State’s long-simmering prison crisis and the history of unsuccessful attempts to fix it. See the photographs of conditions in California prison that helped sway the court’s decision here.

Early on a bright, chilly January morning, Donald Specter walks into a soaring, wood-paneled federal courtroom in San Francisco. Standing before a judge in the nearly empty chamber, Specter begins to relentlessly pick apart a series of guards and administrators from nearby San Quentin State Prison. Slender, with thinning hair, plain glasses, and a gray beard in need of a trim, the 56-year-old strikes an unassuming presence. He speaks in such low-key tones that I strain to hear him at times, and his constant fumbling of papers gives him an absentminded air. Yet few people have more insight into the workings—or rather, the failings—of California’s vast, violent corrections system.

As prison officials take the stand, Specter bores into them about the dismal state of death row at the maximum-security lockup, which is currently at 157 percent capacity. First, there is the question of cleaning supplies: Staffers explain in tedious detail the procedures for purchasing soap, brushes, and buckets, yet can’t say whether inmates actually receive them. A plant manager insists that the bird droppings littering the cell block aren’t a problem, even though the state has described them as “excessive.” An hour is spent on laundry; an official admits he does not know why many death-row inmates wash their clothing and sheets in the toilets. This is followed by a lengthy discussion of whether the law library is adequately stocked.

This mind-numbing dissection of the prison’s inner workings (which went on to include a discussion of the “stalactites of slime” growing in the showers) displays the uniquely dysfunctional way that California manages its desperately overcrowded, shockingly expensive prisons. Which is to say that it doesn’t—Specter does. He’s not a warden or a state employee, but a public interest lawyer who heads the Prison Law Office, an inmate-rights organization whose tiny size gives no hint of its outsized influence. Over the past 32 years, it has won a long string of class action lawsuits against the state. Judges have repeatedly found that California has violated the constitutional guarantee against cruel and unusual punishment and ordered sweeping improvements. In each case, the Prison Law Office has won the right to oversee the fixes, which can take ages; the case heard in January is about 29 years old. Specter and his 11 colleagues currently oversee court orders covering medical, dental, and mental health care for inmates; disabled prisoners; the parole system; and juvenile prisons, among others. The firm’s $3 million budget is largely supplied by the state, which has to pay the plaintiffs’ fees every time it loses a case, which is just about every time.

“We don’t like to say it, but they practically run things,” explains Jeanne Woodford, who went from being a guard at San Quentin to becoming its warden and then the head of the state corrections department under Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger until she quit in frustration two years ago. “The bureaucracy, the way it is structured, cannot keep up with what they have to do at all. Under the normal process, it takes a year to change a rule, a simple rule. The court says, ‘Do this,’ and you just do it. Believe me, we’d get none of the resources we really need if it weren’t for the litigation and the Prison Law Office.”

Even James Tilton, secretary of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, admitted in an interview before his sudden resignation in April that Specter’s work serves a purpose. “I’m trying to break that old system down,” he said, “but there are some areas where the litigation can be helpful.”

Specter doesn’t embrace the burden of reforming the prison system one lawsuit at a time, but he sees little alternative. “I’ve tried persuasion,” he says. “We tried coercion. We’ve tried the press. I haven’t found anything else except litigation and the courts. As frustrating as litigation is, it’s the only thing that I’ve seen that’s effective—and it’s not very effective.”

California’s archipelago of 33 prisons houses more than 170,000 inmates, nearly twice the number it was designed to safely hold. Almost all of its facilities are bursting at the seams: More than 16,000 prisoners sleep on what are known as “ugly beds”—extra bunks stuffed into cells, gyms, dayrooms, and hallways. Schwarzenegger has referred to the system as a “powder keg”; in October 2006, he declared a state of emergency, citing the effects of overcrowding—electrical blackouts, sewage spills, dozens of riots, and more than 1,600 attacks on prison guards in the previous year. Last year, a nonpartisan state oversight agency declared the prison system to be “in a tailspin that threatens public safety and raises the risk of fiscal disaster.”

There is little disagreement that the status quo is unsustainable, yet the system just keeps on ballooning. Even as Schwarzenegger has promised reform, the corrections budget has exploded during his term, from $4.7 billion in fiscal 2004 to nearly $10 billion in fiscal 2007, or about $49,000 for each adult inmate. In contrast, the 220,000-student University of California system gets less than $4 billion annually. The prisons’ operating costs do not include the $7.7 billion that Schwarzenegger and the Legislature have agreed to spend on adding thousands of new beds to ease overcrowding. Nor does it include the additional $7 billion the state will spend to improve health care for prisoners—as mandated by yet another federal case won by the Prison Law Office.

Meanwhile, services for prisoners have all but collapsed, from literacy classes (nearly one-fifth of California’s inmates leave prison totally illiterate despite a law mandating that they read at a ninth-grade level before release) to medical care. In 2005, after a federal judge found that an inmate a week was dying due to incompetence or inadequate care, he placed the prison health care system under a court-appointed administrator. “This statistic, awful as it is, barely provides a window into the waste of human life occurring behind California’s prison walls,” wrote the exasperated judge.

Since peaking in 1992, the state’s violent crime rate has dropped 53 percent. Even if the drop can be attributed to fewer criminals on the streets—which some experts dispute—it does not fully explain why the prison population has nearly doubled since 1990. The number of inmates entering prison with new felony convictions has not risen much in the past decade; last year, around 34 percent of the 139,000 incoming inmates had new convictions. But a startling 51 percent of the new admissions were parole violators, mostly serving brief sentences for breaking their terms of release. At any given moment, about 11 percent of all California prisoners are parolees back behind bars for technical violations. The state has the highest recidivism rate in the country, close to 70 percent—compared with about 50 percent nationwide.

California’s ills are exceptional, but they provide a warning about the enormous costs of a system singularly focused on punishment over rehabilitation. For more than three decades, California has been trapped in a self-perpetuating cycle where putting more people in prison for longer periods of time has become the answer to every new crime to capture the public’s attention—from drug dealing and gangbanging to tragic child abductions. Spurred on by a powerful prison guards’ union and politicians afraid of looking soft on crime, corrections has become a bottomless pit, where countless lives and dollars disappear year after year. And now that it has metastasized to the point where even a tough-guy governor and the guards agree that the prisons must be downsized or else (see “Taming of the Screws“), every attempt at change seems stymied by inertia. The sheer size of the system has become the biggest obstacle to finding alternatives to warehousing criminals without preparing them for anything more than another cycle of incarceration. “The public believes the prison population reflects the crime rate,” says James Austin, a corrections consultant who has served on several prison-reform panels in California. “That’s just not true. It’s because of California’s policies and the way it runs the system.”

Arnold Schwarzenegger stormed into the governor’s office in 2003 after winning a recall election against his Democratic predecessor, Gray Davis. The former action hero sought to turn his larger-than-life personality into equally grand results, especially in the state’s ineffective prisons. As one of his first official acts, he chose a reform-minded administrator named Rod Hickman to head his corrections department and help figure out “how to put this broken system back together.” He even amended the name of the California Department of Corrections, adding the word “rehabilitation.”

The $49,000 Question

California spends around $49,000 annually per adult inmate, nearly 4 times Mississippi, which spends $13,300. Where does the money go? A partial breakdown:

|

Security |

$20,429 |

|

Medical services |

$7,669 |

|

Parole operations |

$4,436 |

|

Facility operations |

$3,938 |

|

Administration |

$2,871 |

|

Psychiatric services |

$1,403 |

|

Food |

$1,377 |

|

Education |

$687 |

|

Records |

$513 |

|

Vocational education |

$289 |

|

Inmate welfare fund |

$282 |

|

Clothing |

$152 |

|

Religion |

$53 |

|

Activities |

$23 |

|

Library |

$23 |

|

Transportation |

$15 |

|

Sources: Bureau of Justice Statistics; California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation; National Association of State Budget Officers |

|

Initially, Schwarzenegger signaled a potential sea change from the get-tough approach his predecessors had taken for three decades. Like many states, in the late 1970s California was swept up by a bipartisan insistence that government needed to punish, not coddle, criminals. He may have been known as “Governor Moonbeam,” but it was Democratic Gov. Jerry Brown who kicked off the state’s embrace of harsh sentencing in the mid-’70s. The penal code was changed in 1976 to state that “the purpose of imprisonment for crime is punishment.” Dozens of tough laws were passed under the governors that followed, including stricter sentences, fewer opportunities for release for good behavior, and an early, sweeping three-strikes law. Predictably, the state prison system grew exponentially. In 1970 California had 12 prisons and 23,000 prisoners; 30 years later, it had 21 new prisons and six times more inmates.

There was no lack of blueprints to guide Schwarzenegger’s vow to fix the prisons while still ensuring public safety. Few prison systems have been more thoroughly studied than California’s. Various official panels have identified overcrowding as untenable and have recommended shrinking the number of prisoners with methods proven to rehabilitate inmates and reduce recidivism.

Early on, Schwarzenegger’s corrections department endorsed these “evidence based” solutions. A large body of data has demonstrated that smart programs that rely on treatment, and include carrots and sticks, can provide some inmates the skills to manage their lives without resorting to crime. For the tens of thousands of inmates who cannot read, even a modest amount of education can put jobs within reach. For inmates suffering from mental illness—up to 30 percent of California’s prisoners—a combination of therapy, medication, and counseling both inside and outside of prison can reduce recidivism. Between 50 and 75 percent of California’s inmates have substance abuse problems, but only 11 percent receive alcohol or drug treatment, less than half the national average. Yet, according to a landmark study by the Washington State Institute for Public Policy, intensive drug-treatment programs for prisoners reduce their chances of reoffending by an average of 17 percent. For every dollar invested in substantive vocational, therapy, or substance abuse programs for inmates and parolees, states can save anywhere from $2 to $98 in the form of lower costs for everything from prisons to courts to police.

But there was no greater statement of the governor’s fresh agenda than his attempt to fix the parole system so that it might actually keep parolees out of prison. No matter what his crime, every single inmate in California is put on parole for at least one year—and as many as three—after release, a more stringent requirement than nearly any other state’s. This leaves parole agents overworked, and most inmates do not receive adequate support in looking for jobs, therapy, or drug rehab. Parole has become a series of trip wires that, when crossed, can put parolees back in prison for months at a time. Last year, 21,000 parolees returned to prison for committing new crimes. More than 70,000 were sent back for “administrative” infractions, such as failing to report to their parole agents on time, changing addresses without authorization, or drug use or possession. Given that a majority of parolees have serious substance abuse problems, are mentally ill, or both, these violations can be chronic. Many parolees who have committed no new crimes get churned in and out of prison in what some refer to as “life on the installment plan.”

In early 2004, Schwarzenegger announced the New Parole Model, a combination of residential drug treatment, electronic home detention, and halfway houses that was designed to keep parole violators out of prison. Corrections Secretary Hickman said it would slash the prison population by 13,000 in a few years. He was so confident that he warned local politicians they would have to wrestle over which prisons to close. But the policy encountered staunch resistance from the prison guards’ union as well as victims’ rights groups, which produced a television ad campaign that suggested that hardened criminals were being set free. Confronted by institutional obstinacy and political fearmongering, Schwarzenegger caved. In April 2005, he quietly and abruptly abandoned the New Parole Model. Three years later, the prison population remains at a crisis level. The state has forecast that, without any changes to the parole system, it will grow by 13 percent, to 192,000, in the next five years.

Michael Brady sits in a small children’s playroom just off the main visiting hall at San Quentin State Prison, considering the case of Bob R. A sad-looking middle-aged white man with a goatee, Bob has the rough, red face of a serious drinker. He wears a standard-issue bright orange jumpsuit and is shackled at the waist. There are Winnie the Pooh posters taped to the walls, and brightly colored toy trucks, but the air is thick and oppressive.

Brady is a deputy commissioner on California’s parole board; he is, in effect, judge and jury for parolees who have been arrested for violating the terms of their release, the so-called technical violators. Previously, he was a deputy secretary in the corrections department and helped design the New Parole Model. Now he’s hearing cases, most of which last less than 20 minutes.

Brady quickly peruses the file and notes that Bob, who had his parole revoked once before after serving 16 months for a fraud conviction, recently “absconded” for 43 days without reporting to his parole agent.

“You have an alcohol problem,” Brady says. “When you drink you don’t report, right?”

Bob admits that he was on something of a bender and trying to tend to his wife, who’s sick with liver disease. He unfolds a tattered handwritten note spelling out his troubles— alcoholism, homelessness, failure to find work. “Please help,” it concludes.

Brady gives him what he asks for, a six-month placement in a privately run residential rehab program, but only after Bob serves a three-month sentence, what is known as “six with half,” meaning the parolee serves only half the stated time of six months.

That may sound like a modest punishment, but such sentences can be debilitating; not only do they cause serious disruptions in the lives of parolees, who often lose jobs, apartments, and cars while inside, they condemn them to one of the worst and most poorly designed areas of prison life, the “reception center.” Reception centers are intended to be temporary homes for newly arrived inmates, where they are tested, treated for urgent medical problems, and then assessed for more permanent prison assignments elsewhere in the state. But because parole violators receive such short terms, they never leave what are among the prisons’ most crowded and disease-ridden sections.

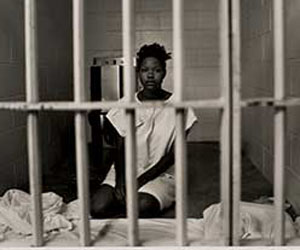

Take the reception center in the desert city of Lancaster, just north of Los Angeles. The prison there, designed for 1,350 inmates, holds nearly 5,000 men, nearly half in its reception center. Many newly arrived prisoners stay in open gymnasiums jammed with rows of triple bunks, self-segregated along strict racial lines. They are stuck inside for 22 hours a day, leaving only for meals and twice-a-week visits to the yard. “We’re just warehoused. There’s nothing to do at all,” says Vernon Bell Jr., who was sent to Lancaster for threatening his parole agent.

The reception center at San Quentin is even starker. Just inside the center, in the prison’s West Block, are three tiny wire cages for inmates either waiting for a transfer or who have caused trouble. On a visit this winter, the three cages held men barely able to move in the narrow enclosures. Just inside the interior doors to the shadowy block were two more cages, both filled. Above rose five tiers of cells, some of the doors left open as the inmates simply roamed at will. Each cell is 4 feet by 12 feet, with a double bunk, an open toilet, and a small sink. It is cacophonous, and a constant rain of refuse floats down from the open tiers. The guards chat with each other and sit at battered desks. The nearly 900 inmates, the majority of them parole violators, spend most of the day indoors. They may get a couple of trips a week to the yard, but other than that they receive no “programming,” which means no rehab, no classes, no vocational training. They get no contact visits from their families and are permitted no telephone calls, except to attorneys. This is where Bob R. and the 13 other parolees Brady will see on this winter morning will end up.

Following Bob, the melancholy parade continues with Mr. Lewis, a young black man who takes numerous medications for schizophrenia and the voices he says he hears inside his head. He failed to report to his parole agent immediately after release from San Quentin because, he explains haltingly, he got on the wrong bus outside the prison. Lost and confused, he called 911 and was arrested. “I see people every day who are so seriously mentally ill that I have to send them to a doctor just to get them stabilized to talk to them,” Brady says, and that is what he orders for Lewis before sending him to the reception center. “The prisons have become our mental institutions.”

The US prison population has doubled since 1990. It has increased 367% since 1980.

Walt is one of several of the morning’s supplicants whom Brady greets like an old friend. “What are you doing here again, my man?” Brady asks. Walt, a 28-year-old who appeared at a revocation hearing less than a year earlier, nods warmly and then tries to explain away an apparent crack buy witnessed by a police officer. It’s hard to put one past the 56-year-old former criminal defense lawyer; 10 years ago, before he started working for the state, Brady fought addictions to alcohol, cocaine, and meth, which landed him in prison for a year. That was followed by a 100-day stint for violating parole and a return to sobriety. He is unmoved by Walt’s convoluted explanation and insists on rehab. Walt agrees, but first there’s the prison time.

Next, Tyler explains how he got arrested after a dispute over a credit card. It has been six months since he served some time for a previous parole violation. “I don’t want to see you again,” Brady scolds after handing out a brief term and a rehab order. Tyler responds with a smirk. “I don’t want to see you again, either.”

Over the past year, Schwarzenegger has thrown several Hail Mary passes in a desperate attempt to ease the crisis. In January, he proposed the release of more than 22,000 nonviolent inmates with very short terms or close-to-completed longer terms. Tilton, the corrections chief at the time, was less than enthusiastic, saying he endorsed the proposal only because of a looming $17 billion budget shortfall. “I’m not a fan of early release,” he said.

California legislators said they would fight such a move. “They’re taking the easy way out, just releasing them, but it’s not the easy way because they’ll just end up back in prison later,” said Todd Spitzer, a Republican from Orange County who heads a state Assembly committee on prison issues. Schwarzenegger flip-flopped in May, dropping the early release plan, saying that the prison population was starting to inch down on its own.

LAST SUPPERS

391 prisoners have been executed in Texas since 1982. Nearly 1 in 5 declined a last meal. Of the 317 who ate one:

22% asked for fried chicken.

16% asked for steak. 1 requested filet mignon.

14% asked for a double-meat cheeseburger.

49% asked for a side of fries. 1 ordered “freedom fries.”

Most popular drink: Coke, followed by tea, milk, and Dr. Pepper

Oddest meal request: A jar of dill pickles

Denied: 1 request for bubble gum

Most specific request: 10 pieces crispy fried chicken (leg quarters); 2 double-meat cheeseburgers with a side order of sliced onions, pickles, and tomatoes, mayonnaise, ketchup on the side, salt and pepper, lettuce if possible; 3 deep-fried pork chops, breaded, trimmed, and well-done; 1 small chef salad with chopped ham and Thousand Island dressing; 1 large order of french fries cooked with onions; 5 big buttermilk biscuits with butter; 4 jalapeno peppers; 2 Sprites; 2 Cokes; 1 pint rocky road ice cream; 1 bowl of peach cobbler or apple pie. —Jen Phillips

Last meal of Oregon inmate Harry Moore

Schwarzenegger is also falling back on the solution of building bigger warehouses because the old ones have filled up. Last year, he approved $7.7 billion in new prison construction, a move his office hailed as an “important step toward solving California’s prison overcrowding crisis.” The massive project will add as many as 16,000 regular prison beds and an additional 16,000 beds in community-based reentry facilities for soon-to-be-released inmates. The governor’s insistence that the plan will serve existing prisoners rather than prepare for new ones has not placated those who insist the money would be better spent on reducing recidivism, as states such as Kansas and Texas are doing. “That is just the stupidest thing you could do,” says Michael Jacobson, director of the Vera Institute of Justice and the author of Downsizing Prisons. “You get nothing by doing all that building, nothing in the way of getting better outcomes.”

California would have to reduce its inmate population by more than 15 percent just to begin to function effectively, says James Austin, the prison consultant, who helped draft the Roadmap, one of the state’s recent prison-reform plans. But reform, he says, is pointless unless it’s accompanied by downsizing. “I don’t care how good you manage; you can’t do anything positive with the population they have now.” In April, the Democratic president pro tem of the state Senate asked Schwarzenegger to clarify how the policies of early release and new beds fit together. “With all of the proposals out there,” he wrote, “the prison population is a bouncing ball; we have no target.”

The governor’s spokeswoman, Lisa Page, says the prison expansion program “will reform and reduce the prison population by focusing on rehabilitating the state’s current prisoners,” while any early releases would free up space for treatment programs.

The latest proposals have left some experts throwing up their hands in frustration over another lost opportunity for reform. “Either we have a governor who lives in Hollywood and believes that wishing makes it so, or, more cynically, it’s government by press conference,” complains Barry Krisberg, president of the National Council on Crime and Delinquency and a member of the Roadmap panel. “The governor has continually fallen down on action. He has not delivered anything he has said he would.”

As the governor wrestles with a paralyzed bureaucracy and tries to build his way out of the crisis, much of the responsibility for real change remains in the hands of the courts and the Prison Law Office. Fed up with the piecemeal efforts, and convinced that overpopulation is at the root of everything wrong in the prisons, Donald Specter and his team are now pushing the federal courts to order the state to slash its inmate population by 30,000. At press time, the Prison Law Office and the state were in intense negotiations to come up with a settlement.

Before he became the third corrections secretary to step down since 2006, Tilton said that he looked forward to implementing the changes that would get Specter out of his hair once and for all.

“Do you know how many times I’ve heard that?” responds Specter, sitting in his cluttered office not far from the gates of San Quentin, wearing jeans, sneakers, and a faded plaid shirt. “Every new guy running corrections for the past 20 years has said he’s going to put a stop to all the litigation. I’ve stopped blaming the head of the system, because I’ve started to see it doesn’t matter too much who is in that job.

“Schwarzenegger could put us out of business if he wanted to just by doing what he said he would do,” Specter sighs. “Everyone in this office would go home tomorrow if conditions permitted. But once again, the governor is letting the courts decide. I’m not sure that’s the best way to manage.”

And so the Prison Law Office continues to micromanage the monster, fighting what often seems like an absurd battle. In their recent case on the conditions at San Quentin’s death row, Specter and his colleagues produced photographs of laundry carts covered in bird droppings and another that contained a putrefying mouse. Lawyers from the state attorney general’s office admitted that the photos pictured “what appeared to be a dead mouse in a laundry cart.” But, they insisted, “the mouse had not started to decay.”

Life Is Cheap

It costs more than $117 million each year to keep 671 men and women on California’s death row. Here’s a snapshot of some of the costs of executing a killer there—and what it would cost to keep him locked up for life. —Celia Perry

|

LIFE WITHOUT PAROLE |

DEATH PENALTY |

WHY DOES IT COST MORE? |

|

|

Trial |

$900,000 (average) |

$2.7 million (average) |

Longer trial, additional legal staff, expert witnesses, and extra security |

|

Direct appeal |

$105/hour |

$140/hour |

State pays capital defense attorneys more, and their workload is bigger. |

|

Habeas corpus |

$0 |

$200,000/year |

State provides lawyers to death-row inmates, but not lifers. |

|

Incarceration |

$35,000/year |

$125,000/year |

Death-row inmates get their own cells and extra guards. They spend an average of 20 years on death row. |

|

Last meal and execution |

$0 |

$50 maximum (meal); $90 (3-drug cocktail) |

|