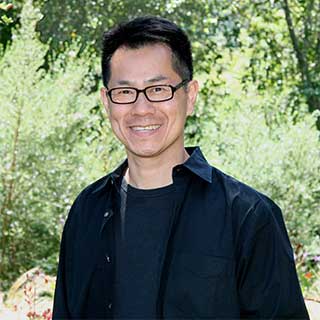

Today, Chinese film icons like Jet Li, Ziyi Zhang, and Jackie Chan are used to getting top billing and attending red carpet premieres. But as filmmaker Arthur Dong shows in his latest documentary, Hollywood Chinese, for most of the 20th century, Asian movie roles were played by white actors in yellowface, leaving Asian actors with bit parts like opium-den owners or inscrutable servants. Pioneering work by Chinese-Americans, both in front of and behind the camera, paved the way for the current crop of Chinese-born stars by fighting with directors for more accurate depictions of themselves onscreen, and eventually, by creating their own worlds where Chinese are not outsiders, but sympathetic protagonists.

Born and raised in San Francisco’s Chinatown, Dong made Hollywood Chinese to examine his own hybrid culture and how it has been represented in film. He combed through hundreds of hours of archival footage and promotional materials for films dating back to the 1916 silent movie The Curse of Quon Gwon, which is now thought to be the earliest Chinese-American film ever made. Even more unusual for the time, it was directed by a woman, Marion Wong, and shot entirely in her hometown of Oakland, California. Hollywood Chinese also features disarmingly intimate interviews with Nancy Kwan (the original Suzie Wong), Ang Lee, Amy Tan, and other Chinese-American celebrities who tell the story of how their heritage has limited their careers. Actor James Hong describes growing up in Minnesota, only to spend more than a third of his career playing kung fu masters. Joan Chen recalls struggling to learn how to speak pidgin English for Tai-Pan and notes that when The Last Emperor won nine Oscars, including Best Picture, she didn’t get a single film offer immediately afterwards, though her white co-stars did.

Packed with priceless if sometimes cringeworthy scenes—John Wayne in yellowface in The Conqueror; Charlie Chan speaking “fortune-cookie Chinese”; Nancy Kwan singing “I Enjoy Being a Girl”—Hollywood Chinese is a celebration of Chinese-American film history. It’s also the story of how the movie business has gradually changed for the better; now Asian directors like Wayne Wang have the freedom to make films such as the innovative Chan Is Missing or the insipid Maid in Manhattan. As Dong tells us, it’s been a long journey from pidgin-speaking servants in Chinatown to the Asian high-school jocks in Better Luck Tomorrow.

Hollywood Chinese opens April 11, 2008 in San Francisco and Oakland; in New Jersey, Hawaii, Arizona, North Carolina in April; Los Angeles and New York in May. For release dates, go here. Dong spoke to Mother Jones while one the road promoting the film.

Mother Jones: What films influenced you most as you grew up?

Arthur Dong: I was born and raised in San Francisco’s Chinatown, where there were movie theaters that used to show Hong Kong movies. That’s where I hung out. I was brought up on a very diverse set of Chinese images on the screen: lovers, villains, mother-in-laws that were mean, parents that were great, and kids, just like in American movies—the whole spectrum of representation. So I had a pretty solid basis for how I saw my face on the screen. In early 1960s the Chinatown theaters ran big-budget Hollywood pictures—The World of Suzie Wong and Flower Drum Song—and everyone was so excited. And I started to see more Hollywood films from that time on.

MJ: What are examples of Asian roles in the media today that neither whitewash ethnicity nor reproduce stereotypes?

AD: I think BD Wong’s role in Law and Order: SVU is a great example. He plays a forensics psychiatrist that is…a forensics psychiatrist, and so there! And you can’t deny he’s Asian American, but that’s not the crux of his role. As opposed to Lucy Liu in Cashmere Mafia. I couldn’t watch that. It’s not even a good show, but she has a hot boyfriend, and that’s great! Not that to be Asian-American you have to be totally hot. But she’s not dating a white guy, which is such a pattern that you see in the media. On one hand you want to rag about the quality of the show, but on the second hand, people are watching it. And for that particular show, I think that’s a good thing.

MJ: In Hollywood Chinese, actress Louise Rainer (who had played in yellowface in The Good Earth) brought up the idea that the ethnicity of the actor is not important. Actors are actors, she says, and they should be able to play Chinese, African-Americans, and Caucasians, because that’s the nature of their job.

AD: She’s talking about her right to play a role because she is an actress, regardless of race. This is what Asian-American actors are asking for as well: It’s called color-blind casting. But there’s an imbalance in that white actors can play anything, but not Asian American actors. If everyone was on an even playing field, I could hear her argument. If BD Wong can play president of United States—and I guess in 24 there is a black president—then her statement cannot be debated. But because there is so little opportunity for actors from certain communities to get those roles, it’s just not practical to rely on color-blind casting. You can’t have blackface anymore. But just a few years ago [in Grindhouse] we had Nicholas Cage playing Fu Manchu! Gimme a break!

MJ: Are there similarities between the experience of being gay and being Asian that struck you as you did this film?

AD: Oh, totally. But what’s interesting is not the similarities but the differences. With the gays, on certain level you can be invisible. But you can’t be invisible being Asian. You can’t say “Hi, I’m white!” The similarities are about being marginalized. The problem with representation in the media has very much to do with the conflicts between groups in the world. If you talk about Iraq, al Qaeda, Darfur, even Taiwan, representation is a part of that problem. Because we don’t know the “other” and what we know about the “other” may be just from the media. And if Hollywood is the global producer for [media] products all around the world, that’s of concern. If all audiences around the world know of America is what they see from Hollywood, then we’re in trouble.

MJ: What did you find most surprising when making this film?

AD: I purposely cast the film with mostly celebrities. And I picked their stories specifically for what they represented: Joan Chen as the ingénue story; James Hong represented the Zen master experience in Hollywood; Ang Lee represented the foreign-born. But what was surprising to me is that they opened up and really became real people, not just celebrities. They were able to talk about their experience and put in the historical [context]. And that made it easier for me in the editing room. They gave me that flow, that balance between a historical/sociological study and personal experience.

I made this film for film lovers. I do want it to be entertaining and enjoyable. I did Hollywood Chinese with humor; I purposely built in humor because that’s part of my strategy as a filmmaker. I frame these issues that I’m personally interested in and want to explore, but frame it in a way that’s accessible and user-friendly.

MJ: Are you seeing fewer stereotypical Asian images in film today than 20 years ago?

AD: The one stereotype that hasn’t disappeared is the Triads. In the early part of the 20th century, you had the tong wars and the opium dens. Now it’s the Triads with the heroin. Any TV show that you click on that’s set in Chinatown, you can pretty much bet that there’s going to be a Triad scene. And unfortunately, that’s where a lot of the work is for Asian-American actors. And if you want to pay the mortgage, or pay your kid’s college tuition, you gotta take the roles, you know?

Other roles we’re getting now are the reporter, the grocers; we’re getting the doctors. Now they have all these Asian-American coroners on TV. At least they speak English well. It’s the model minority stereotype: We’re all scientists and engineers and we’re all smart. But there’s a backlash to that. Part of the problem of being labeled a model minority is that everyone thinks you’ve made it, but that’s far from the case. You can see that in the horrific stories where undocumented workers are trying to get into the country. That’s the backlash.

I think it’s wonderful that even in high schools now they’re starting to teach media literacy classes. Film is so subliminal. For example, a third of the way into Juno you see the first Asian character with any substantial lines. And she’s a bigoted Christian picketing an abortion clinic and she speaks with an accent. What does that tell the audience? That Asians are still outsiders. They don’t belong in our world. I’m sure glad I was not in the audience, watching this in the Midwest, 16 years old, Asian-American, surrounded by my friends and classmates, who are all white, laughing at this character.