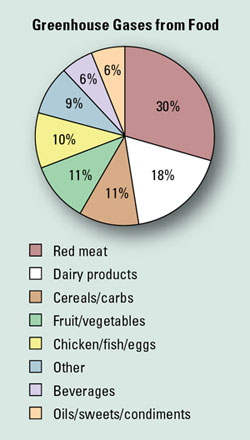

The number of miles your food travels from farm to plate makes a difference in your personal climate-change footprint. But not as much as eating red meat and dairy, which are responsible for nearly half of all food-related greenhouse gas emissions for an average U.S. household. New research published in Environmental Science & Technology finds it’s how food is produced, not how far it’s transported, that matters most for global warming. Christopher Weber and Scott Matthews of Carnegie Mellon University conducted a life-cycle assessment of greenhouse gases emitted during all stages of growing and transporting food. They found transportation creates only 11% of the 8.1 metric tons of greenhouse gases that an average U.S. household generates annually from food consumption. The agricultural and industrial practices that go into growing and harvesting food create 83%.

The number of miles your food travels from farm to plate makes a difference in your personal climate-change footprint. But not as much as eating red meat and dairy, which are responsible for nearly half of all food-related greenhouse gas emissions for an average U.S. household. New research published in Environmental Science & Technology finds it’s how food is produced, not how far it’s transported, that matters most for global warming. Christopher Weber and Scott Matthews of Carnegie Mellon University conducted a life-cycle assessment of greenhouse gases emitted during all stages of growing and transporting food. They found transportation creates only 11% of the 8.1 metric tons of greenhouse gases that an average U.S. household generates annually from food consumption. The agricultural and industrial practices that go into growing and harvesting food create 83%.

Switching to a totally local diet is equivalent to driving about 1000 miles less per year. Yet a relatively small dietary shift can accomplish about the same. Replacing red meat and dairy with chicken, fish, or eggs for one day per week reduces emissions equal to 760 miles per year of driving, say the study’s authors. And switching to vegetables one day per week cuts the equivalent of driving 1160 miles per year.

Why not all of the above? Though there are other factors to consider when we choose our foods, everything from the ecological costs of hunting wildlife (fish), to fertilizer runoff and oceanic dead zones (dairy), to cruelty issues (eggs). As always, and as your mama said, veggies rule.

Julia Whitty is Mother Jones’ environmental correspondent, lecturer, and 2008 winner of the Kiriyama Prize and the John Burroughs Medal Award. You can read from her new book, The Fragile Edge, and other writings, here.