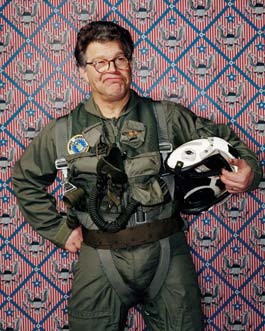

Photo: F. Scott Schafer/Corbis Outline

In the spacious living room of his Minneapolis town house, Al Franken is trying to explain why he’s stopping himself from telling me a joke. For the last 18 months, he’s gone to every spaghetti dinner, bean feed, and burger bash he could find, many in small conservative towns, to campaign for Minnesota Democrats, road test his new senatorial act, and raise more than $1 million for candidates nationwide. It’s an early, aggressive strategy, but the jokes—the jokes are all anyone wants to talk about. When Franken delivered a long speech explaining his motivation to run, the press picked apart the one-liners. When a poll showed him doing well against the incumbent Republican, Norm Coleman, the state gop pointed to Franken’s history of off-color jokes (many about the president’s codpiece in the “Mission Accomplished” photo op). “I was discussing this with [fellow comedian Robert] Smigel,” Franken says. “What Robert says is, ‘Any other candidate who made jokes of this quality would be lauded. But with you, it’s sort of like they want people to come away saying, God, he was great! I didn’t laugh.'” He cracks up. Then, switching back to candidate mode, he goes on, “That’s why I started early—because I want to get that out of the way.”

The head start offers other advantages as well, like a sense of which jokes are too blue, and how to best smooth over Franken’s notoriously prickly personality. The jokes, for now, can stay, so long as the edgy awkwardness that fuels so many comedians’ humor doesn’t come off as imperiousness. Because that doesn’t play well in Minnesota, as Franken, who grew up there, undoubtedly knows.

But what does? Jesse Ventura’s 1998 gubernatorial victory as an independent is only the best-known indicator of Minnesota’s political volatility. Once reliably blue, the state swung right in the 1990s as conservative exurbanites began to outvote the union-dominated mining regions of the North. In 2002, after Democrats were maligned for turning a memorial service for beloved Senator Paul Wellstone into an overcharged political rally, Coleman was elected to the Senate, and the gop took control of the state House of Representatives by a wide margin. But recently, Minnesota Democrats, known as the Democratic-Farmer-Labor Party, or dfl, have been on the rebound. Now the political locus is in the southern part of the state, the kind of once solidly conservative, now war-weary region that helped hand Congress to the Democrats. In 2006 the 1st Congressional District, which had been represented by a conservative Republican for 12 years, elected a Democratic Iraq veteran.

Franken spends a lot of time in the 1st. One spring afternoon, he stands before some 50 retirees gathered at a coffee shop in the town of St. James (pop. 4,416). “Is there something you’d like me to know?” he begins. “Something I probably wouldn’t know about?” A woman brings up the community’s changing makeup; manufacturing plants have brought an influx of Hispanics. Franken cuts to the quick. “Is it a strain? Is it a good thing?”

“It’s good for children to grow up in a multicultural community. But it makes things…” She pauses. “Interesting.”

Franken pushes, calmly. “Is ‘interesting’ a euphemism for something else?” It’s an unusual tack for a candidate to take, confronting a voter on a sensitive issue, and the woman is nonplussed. “It’s not a strain, just a challenge,” she says, casting an exasperated glance around the room. “Somebody help me out here.”

A couple people jump in, but Franken quickly takes over. He eases into a discussion of immigration policy, dipping a tea bag into a mug as he chats. He laughs. He jokes. It’s clear he’s done his homework. The tension dissipates.

When he gets to the war, Franken explains he doesn’t support an immediate pullout—”it would be a bloodbath”—but he notes his support for withdrawal timetables and, by the way, his four uso trips to Iraq. (He chronicled one in Mother Jones in 2004.) This is met with applause. Then Franken begins laying out specific benchmarks for the Iraqis. If he’s trying to prove his wonk credentials, it comes at the cost of the moment. People’s eyes glaze over.

Still, afterward, it’s clear the crowd has forgiven any rhetorical awkwardness—most are delighted Franken showed up at all. “I’m impressed that he would come to a community the size of St. James this early in the campaign,” says Teresa Holmquist, who works for the federal Farm Service Agency. Her father chimes in, “He’s doing the right thing. He needs to talk to the little people, find out what our problems are.”

Franken’s incessant campaigning in towns like St. James is a smart strategy for a political neophyte blessed with celebrity cachet; it’s enabled him to introduce himself to local voters and to pile up IOUs with party honchos. It’s also a necessity given the state’s peculiar nomination system: Democrats choose their nominees in Iowa-like caucuses in March. Franken’s main rival is Mike Ciresi, a longtime state party fixture and one of the nation’s most successful trial lawyers—he won a massive tobacco settlement in the 1990s. The case netted Minnesota $6.6 billion and Ciresi unspecified millions, $101,610 of which he and his wife have donated to Democrats and related organizations since 2002.

But Franken now holds a few chits too: His Midwest Values pac handed out more than $260,000 to candidates in Minnesota and nationwide in the 2006 cycle, and Franken and his wife have personally donated around $70,000 since 2004. “Al Franken has been doing everything right,” says former state party spokesman Nick Kimball. “He has built a lot of good will.”

That good will is on display at a party fundraiser in Fulda (pop. 1,256), where most of the several hundred attendees are old hands in local politics and the adoration is palpable. Everyone, including Ciresi, speaks in front of two “Al Franken for Senate” signs the campaign has put up—Franken’s organization, with nine full-time staffers, a handful of consultants, and a substantial cadre of volunteers, is perhaps the most fully developed campaign of any Senate challenger in the country.

Yet Franken never quite finds his rhythm in Fulda. Engaging in person and relaxed in the coffee-shop setting, in front of this larger crowd he seems to need a TV camera or radio mike to focus him.

But then, you can’t measure Franken by traditional stump-speech standards. Short and stocky, with massive tortoiseshell glasses and an artless fashion sense, he appeals not by being senatorial; when he stumbles over his own words as he works up a lather about George W. Bush, he’s the opposite of a classic politician. But just as with his friend Paul Wellstone, that seems to be one of his main assets. “Al Franken doesn’t just say things to be saying them. I could never see Al Franken not standing by his words of today,” says Katherine Speer, a dfl county chair. “I don’t think it’s in the man’s makeup.”

The same is not often said about Norm Coleman. In 1996, the then-St. Paul mayor, “lifelong Democrat,” and former anti-Vietnam War student activist—who once urged classmates to vote for him because “these conservative kids don’t fuck or get high like we do”—switched parties in a bid for the governor’s seat, only to get beat by Ventura. In 2002, Bush recruited Coleman to run against Wellstone, for whom he’d once served as campaign chair. Senator Coleman voted with the White House 98 percent of the time and supported the Iraq War, but as Bush’s popularity waned, he began attacking the White House.

And so Franken has an opportunity—so long as his well-organized and deep-pocketed campaign doesn’t become a punch line. “I don’t think it’s going to be a problem,” Franken said when we first spoke at his house. His smile faded. “I think Minnesotans can figure out that I’ve been a satirist and not just…” He paused, struggling to make a safe joke. “I’ve had a different career arc than, say…Carrot Top,” he said, finally bursting into laughter.