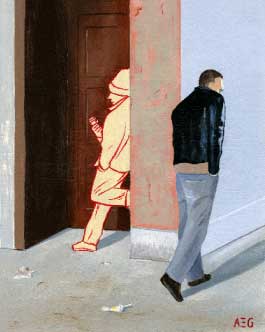

Jerry’s your quintessential streetwise New Yorker, Midnight Cowboy‘s Ratso Rizzo come to life. He lost most of his front teeth years ago when he stumbled off a subway platform while nodding out on heroin, but his smile remains wide and boyish, and it is on nonstop display as we stalk the city’s Ninth Avenue drug corridor, the last vestige of pre-gentrification Hell’s Kitchen. The midday sun is bright as Jerry solicits strangers and old buddies—”You seen noncontrol?”—while conspicuously clutching his pharmacy bag.

“Noncontrol” is shorthand for dealers who specialize in a reverse drug trade: Rather than selling illegal narcotics to addicts, they buy prescription medications from them—”noncontrolled substances” in legal parlance—and AIDS medications are at the core of their business. Jerry (who, like other AIDS patients in this story, has been given an alias) tested HIV-positive a decade ago, after half a lifetime bouncing in and out of lockup for various burglaries, thefts, and armed robberies; ironically, AIDS proved to be his first opportunity to feed his drug habit without going right back to prison. He’d use his New York state Medicaid card to buy prescriptions worth hundreds of dollars, then turn around and sell them on the street for as little as $20 a bottle. “You’d take it, out of desperation,” he sighs. These days he’s clean and not as desperate for cash, so on this particular foray he’s just unloading some painkillers and the Marinol his doctor prescribes to help his appetite. When we finally track down the noncontrol man, Jerry nets $80.

AIDS drugs are among the world’s most expensive pharmaceuticals, and the noncontrol man can resell them for astronomical profits. No estimate exists of the size of the black market in AIDS drugs, but experts agree that it’s grown exponentially as these medications have become widely available in the industrialized world while remaining out of reach in the Third World. In the United States, some black-market pills are bought by pharmacists who turn around and sell them at retail prices. Another branch of the illicit supply line leads to the Caribbean, particularly the Dominican Republic, where AIDS rages with an intensity second only to that of sub-Saharan Africa, and where the drugs’ prohibitive pricing has fueled a hodgepodge trade in pills bought on the streets of New York, and underwritten by the state’s Medicaid program.

The AIDS drug trade has attracted the attention of officials—including the Medicaid fraud unit of the state attorney general. One doctor told me that for the past three years she’s had to notify Medicaid each time she writes a prescription for any of her 300-plus hiv-positive patients. Doctors worry that a crackdown will affect the already tenuous relationship they have with patients, many of whom are distrustful—if not paranoid—at the best of times. Patients who can get Medicaid to pay for their legal drugs but can’t get into treatment for their addiction to illegal ones (according to a 2000 federal study, 57 percent of Americans who need drug treatment can’t get it) will peddle whatever prescription meds they can to feed their habit. And the demand, clearly, is not going away.

To follow the AIDS drug trail, I headed to Santo Domingo, the capital of the Dominican Republic, where I met Dr. Carlos Adon, an AIDS doctor at one of the city’s busiest clinics. Adon studied both drama and medicine, and his manner is as much theatrical as diagnostic. Insatiably social, with a bright smile radiating from an open face, he moves with a youthful fluidity. That’s essential to his work, because he is in constant motion: In between conferring with patients, his receptionist, a mother desperate to get her hiv-positive son out of jail, and a man on the phone who is fruitlessly working him for information about a girlfriend (“She’s coming to see you, isn’t she? She has AIDS, doesn’t she?”), he’ll cut me off mid-sentence when he hears a pleasing riff in the merengue that constantly ricochets around Santo Domingo: “Shhhh! Listen. That’s niiice.”

Much of Adon’s clientele comes from the country’s hinterlands, where hiv infections are both depressingly common and often kept secret. Officially, the national infection rate is just under 2 percent (which would still mean almost 90,000 Dominicans are hiv-positive), but studies suggest that in some regions the real rate is closer to 17 percent. One-sixth of the Dominican Republic’s population is unemployed, and in a country with an $8,000 per capita gdp, AIDS drugs that start at around $200 to $300 for a month’s supply of even one of the cheaper pills are utterly out of reach.

So Adon’s patients get creative. New York dealers sell the medications to the Dominican Republic via middlemen in pharmacies and bodegas, or through family members; some patients are lucky enough to have doctors’ prescriptions to guide them, while others simply take whatever medications their relatives can scrounge up. “People think that, ‘Well, if it worked for Juanita in New York, it will help Maria in Santiago,'” Adon sighs. “They don’t understand the drug interactions.” Adon does a delicate dance between the law and the needs of his patients: He goes to great lengths to avoid getting involved in the black market directly, but will slip patients a name or a phone number, if that’s the only way they’re likely to get on medication. “It is something I cannot fight,” he declares resolutely. “People want to live.”

Carlos, a slight, soft-spoken man who makes a living ferrying tourists around the town of Boca Chica, arrived in Adon’s office in 2000, near death. He’d tested positive a few years before but had been unable to afford the 30,000 pesos, or roughly $1,000, a month for black-market meds. “I don’t even make 8,000 pesos in my good job,” Carlos laughed. Adon started him on an older, cheaper drug combination, and then Carlos’ brother-in-law in the Bronx began buying meds from the noncontrol man—so often, in fact, that Carlos now supplements his $300 monthly income by reselling pills he doesn’t need for about $80 a bottle.

“Medication becomes like money,” says Adon, holding out his hands to cup an imaginary treasure, “like diamonds for somebody, because they see their life in there. And it is in there.”

—