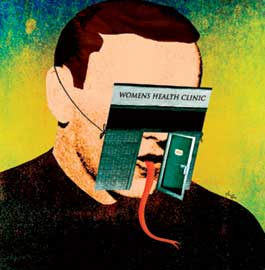

Illustration by: Brian Stauffer

When Troy Newman would answer the phone at Central Women’s Services in Wichita, Kansas, last summer, there was a lot he didn’t mention. The priests who’d been arrested for blocking the abortion clinic’s door. The “truth truck” parked nearby with its billboard of an aborted fetus. The pickets at employees’ homes. He didn’t talk about how all of this had caused the clinic to shut down, save for its still- functioning phone system. He would press the receiver to his ear and intone, “Women’s clinic!” And when a nervous voice at the other end of the line would inquire about abortion services, he would furrow his brow and ask, “Don’t you know that’s a baby?”

The best place to preach against an abortion clinic, Newman has found, is from within one. The national president of Operation Rescue, he bought the clinic—shuttered last May after the pro-life outfit had laid siege to it for more than 15 years—through a front group; now he’s turning it into his organization’s headquarters, complete with a prayer garden and a memorial to the 50,000 unborn children he claims were murdered there.

As pro-lifers have winnowed the number of abortion providers in America by nearly 25 percent since the early 1990s—Wichita now has just one—Operation Rescue has joined several anti-abortion groups converting clinics to their own purposes. “What better way to show that we are winning and demoralize the enemy,” Newman says, “than by shutting down an abortion mill, throwing out the tenants on their face, and taking it over as our headquarters? You lose, we win.”

Beyond the chest thumping, the takeover is part of a long-term strategy for the anti-abortion movement. Organizers such as Newman, the son of a San Diego Army recruiter, are seeking new converts—in particular, women, an estimated 26 million of whom have had an abortion. At the Wichita memorial, Newman says, they will be able to reflect, mourn, memorialize—even name their “babies”—and take action: “Not only can I see a plaque here with my baby’s name on it, and cry here because I killed my baby here,” he imagines visitors saying, “but these people in this building are dedicated to ending the holocaust, and I can join with them hand in hand.”

For all his rhetorical bluster, Newman comes across as a likable guy, an earnest, slightly jockish Southern Californian who looks like he might drink wheatgrass. It’s hard to imagine that he came up with the idea of pasting bloody fetus photos on the sides of trucks, or that his group orchestrated the 1991 Summer of Mercy protests that shut down all three of Wichita’s abortion clinics for nearly two weeks. Indeed, Newman’s amiable demeanor could be one reason why women, not realizing what has happened to the clinic, have often let him usher them in.

By the time I visited in December, the bleak, midcentury facade had been plastered with anti-abortion posters but was otherwise unchanged; one window bore a half-peeled-off sticker reading “Condoms Save Lives.” Inside, Newman pointed to a wall where doctors stored the suction machines used to remove fetuses. He continued down a hall, past a bathroom where a yellow plastic sign said “Place Urine Specimen in Box,” to a glass exit door with security cameras mounted overhead. He paused and said: “We’ve seen women come two steps out this door and heave.” He then stepped over a pile of construction debris and into a whitewashed surgery room, where he was careful to point out a couple of dead cockroaches on the floor, note how the door locked from the inside—to facilitate rapes, he supposed—and claim that tests had detected traces of blood on the walls. “From there they would take the baby,” he said as he walked around a corner into a small kitchen, “and they would dump it down this sink.” The sink held an industrial-strength disposal known in the restaurant industry, Newman said, as the Bone Crusher. When giving the tour to a pregnant woman, he told me he’d flick a switch and listen to it whir.

That Newman owns the clinic—and, thus, the power to tell its story—gives his foes pause. “It’s a little bit frustrating,” says Jeff (an alias he uses for his safety), manager of the Kansas City abortion clinic Aid for Women, which used to send doctors to the Wichita clinic. Operation Rescue’s claim to have found blood on the walls is “ludicrous,” Jeff says; the locks on the doors were most likely relics of the building’s earlier uses, and the Bone Crusher only disposed of blood, while any solid material would have gone to a biohazard disposal company, he adds. Still, Jeff doesn’t believe the conversion tactic is much of an issue. “Are they going to be able to support, say, five of those things?”

Newman certainly isn’t the first pro-lifer to take over a clinic. In 1993, Christian activists in Chattanooga, Tennessee, knocked down most of a clinic and built the National Memorial for the Unborn, a granite wall modeled on the Vietnam Veterans Memorial. In 1994, an anti-abortion foundation bought a clinic in Baton Rouge, Louisiana, put coffins on the front lawn, and renamed the place the American Holocaust Memorial; tours for Christian school groups now include two “blood rooms” sporting what the foundation claims are original stains. Two years later, Leslee Unruh, president of the National Abstinence Clearinghouse in Sioux Falls, South Dakota, converted an abortion clinic into a crisis pregnancy center with a memorial garden where women have left notes such as “I’ll hold you in heaven” and “Please forgive me.” Unruh, who had an abortion she now regrets, believes women like her are often dismissed as unstable or irrational by the pro-choice movement and are shamed or ignored by pro-lifers fixated on the rights of the fetus. “We are the women in the middle,” she says. “We say, ‘Talk to us.’ And that’s why it’s a safe place for them.”

Some pro-choice advocates admit their movement has been slow to tackle the question of healing. Only in the past several years have hot lines such as Exhale and Backline begun providing women with postabortion counseling services. In fact, pro-choice women often need as much help coping with an abortion as those raised to think ending a pregnancy is evil, says Peg Johnston, a clinic director in Binghamton, New York, and the president of the Abortion Conversation Project, which supplies clinics with pamphlets titled “Healthy Coping After an Abortion.” “I think for all we talk about abortion in this country,” she says, “it has never been seen for what it is, which is a complex life decision.”

A banner now hanging in front of the Wichita clinic certainly leaves little room for ambivalence. “The Gates of Hell did NOT prevail!” it proclaims, explaining, a bit preemptively, that the building has been redeemed. Inside, pro-life contractor Bob Burnison is hard at work ripping out drywall. He believes demons still haunt the building; his brother hurt his back working here and has been sidelined for weeks. Burnison recently called in some fellow Christians to beat back the spirits with prayers and Scripture quotes (“All nations will come and worship before you, for your righteous acts have been rewarded”), which are now written in red marker on pieces of paper that adorn bare columns and cinder blocks. Burnison tapes them up elsewhere when it’s time to demolish another wall.

As Newman surveys Burnison’s handiwork from the parking lot, he runs into his neighbor Vallarie Eades, director of the Catholic pregnancy counseling center A Better Choice, which opened next door to the clinic in 1996. Signs in the old clinic windows now refer abortion seekers to Eades, who gives them coffee and flyers with titles such as “Breast Cancer Risk From Abortion.” Eades has been following the clinic renovation, and she wants to know whether the building has been blessed yet. “No,” Newman says, “still waiting for Father Euteneuer to come out and do an exorcism.”