In a democracy, voters are supposed to choose their rulers. But in America it seems to be the other way around. Webster’s on gerrymandering: “[T]he division of a territorial unit into election districts to give one political party an electoral majority in a large number of districts while concentrating the voting strength in of the opposition in as few districts as possible.”

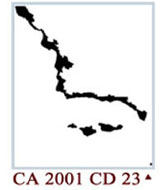

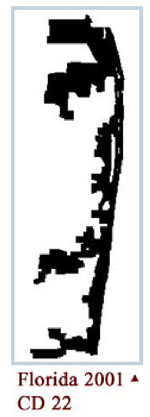

Legislatures have created districts as winding as the Mississippi River, as roundabout as a a u-turn, and as porous as a coral reef—rendering voting little more than a good-faith ritual. Indeed, in 2004 fully 98 percent of incumbents running for re-election to the U.S. House of Representatives held onto their seats—even accounting for retirements and deaths.

Pronounced with a hard “G” the name harkens back to 1812, inspired by Massachusetts’ Governor Elbridge Gerry. Though hardly a new practice, computer software of the past two decades has meant incumbents can use redistricting to benefit like never before.

It turns out that redistricting is easier and cheaper than actually campaigning. In 2001, U.S. Rep. Loretta Sanchez (D-Orange County) admitted that she and her colleagues paid $20,000 to map-maker Michael Berman to preserve their seats. “Twenty thousand is nothing to keep your seat,” Sanchez said. “I spend $2 million (campaigning) every election.”

Sanchez is one of a few incumbents who have gerrymandered their siblings a seat (her sister Linda, in 2002), according to Doug Johnson of the Rose Institute, an expert on the topic.

Three decades ago, another U.S. Representative, democrat Phillip Burton crafted a San Francisco Bay Area district that his brother, John Burton, won in 1974. John later became a powerful force in California state politics, and as state senate leader in 2001, gerrymandered a fellow Democrat out of a seat. Burton’s goal was to prevent State assembly leader Fred Keeley of Santa Cruz from winning the primary for the state Senate and took the city of Santa Cruz, where Keeley had garnered a following, right out of the district. But Burton’s preferred candidate ended up dropped out early, and Keeley didn’t even attempt to campaign in a foreign district, thus a Republican took the seat.

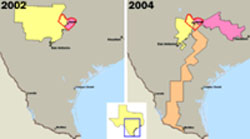

Democrats have controlled redistricting in most states in recent decades, but Republicans have certainly taken charge of late. Legislatures have lost their inhibitions and now follow just the slimmest of rules: for one, chunks of a district have to be connected by a minimum of one census block—the smallest geographic unit for which the Census Bureau tabulates percent data—or a bridge, or a highway. In 2003, the Republicans of Texas, led by Tom DeLay, famously broke the other basic rule: that redistricting should take place only every ten years. Just two years after the last redraw DeLay cleaved the city of Austin into two separate districts, one of which snakes about 300 miles to the border of Mexico. The U.S. Supreme Court upheld the scheme, meaning, for now, anything seems to go.