[Update, 2/9/12: In a politically charged ruling, Spain’s Supreme Court has convicted Garzón of illegal wiretapping and ordered him suspended from the judiciary for 11 years.]

Of all the things that people say about Baltasar Garzón, what they argue over least is the belief that he must have the most dangerous enemies of any man in Spain. As an investigative judge on the nation’s high court, the Audiencia Nacional, Garzón has prosecuted drug traffickers, terrorists, rogue state-security officials, and an assortment of Latin American military figures, including the former Chilean dictator, General Augusto Pinochet. In the Spanish Basque country, threats to Garzón are splashed everywhere in the blood-red graffiti of the separatist group ETA. And last September, Garzón issued a 692-page indictment against Osama bin Laden and 34 of his reputed followers.

It can be unnerving, then, to sit in Garzón’s chambers and watch him work. The security at the Audiencia building in downtown Madrid seems inexplicably lax: Most anyone with a photo ID can step through a metal detector and enter the courthouse. There is rarely a receptionist on Garzón’s floor, so people come and go outside his office, entering with no more than a quick knock. Even the secretary works only part time, and Garzón often answers his own phone, occasionally raising his voice to be heard over the power drill that his law clerks use to punch holes in their thick case files.

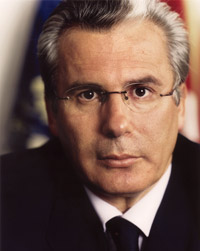

Garzón’s “chambers” are really just a modest office, cluttered with law books and family pictures and the faux period furniture that is standard issue for the Spanish bureaucracy. When a tough-looking Belgian drug suspect shuffles into the office for a hearing one morning, the space seems to get even smaller. Garzón’s bodyguards are nowhere in sight. The judge himself is not an imposing presence; with his soft, handsome face and rimless glasses, he could be the well-meaning doctor on a television soap opera. The police guards who accompany the drug suspect crack off his handcuffs and wait outside the door. A prosecutor, a defense lawyer, and a stenographer pull up chairs around Garzón’s desk. The prisoner sits down directly across from him, barely three feet away.

The accused trafficker sits quietly as Garzón summarizes the Belgian government’s request for his extradition. His hard stare notwithstanding, the suspect finally agrees to return home to face the charges. Garzón then confers briefly with the lawyers before dictating his report in a husky baritone so fast and fluid that it is hard to tell where his sentences begin or end. But such hearings are not always so matter-of-fact. Last May, one of ETA’s more notorious accused killers leaped out of the same witness chair and hurled himself across Garzón’s desk, spewing threats on the judge’s life.

“If something is going to happen, it’s going to happen,” Garzón says later, shrugging a bit. “And when you take on terrorist groups, things happen.”

Garzón is not a persuasively modest man, but he tries to be discreet about the dangers of his job, having been taught not to discuss the security that surrounds him. He is less guarded about drawing lessons from the way he works. When prisoners are treated with respect, he says, they tend to be more cooperative. But even when suspected terrorists refuse to talk, a democratic state cannot afford the long-term political cost of their mistreatment, Garzón insists. He knows that some of his foreign counterparts (U.S. intelligence officials, for example) consider this view anachronistic, even naive. But he believes it is the Americans who are putting themselves at greater risk. The Spanish authorities have been fighting terrorism for a long time, he says, and they have learned some difficult lessons.

“What frightens me is when people start going beyond the limits of the law,” Garzón said. “Taking the right to a defense away from those who are detained at Guantanamo. Establishing a license to kill terrorists. In this country, we know what it means to use this heavy hand. We know that when the fight against terrorism moves outside the law, it becomes very dangerous.”

At a time when the U.S. government remains bitterly at odds with much of Europe over how to confront the dangers of an often frightening new world, the 48-year-old Garzón has emerged as one of Washington’s more resonant critics on the Continent. Almost from the moment the Bush administration declared its war on terror, Garzón has warned that curtailing civil liberties and torturing detainees would undermine public support and, eventually, the rule of law. He does not question the need for aggressive intelligence work, or even the select use of force to fight terror. But he argues for the primacy of a multinational, legal approach over what he describes as a “militaristic” strategy of intelligence gathering, extrajudicial arrests, and military detention. His sprawling indictment of bin Laden last fall—the first to charge the Al Qaeda leader in connection with the September 11 attacks—echoed his insistence that even the most terrible criminals on earth should be dealt with in courts of law. In late December, he sought the extradition of four Al Qaeda suspects from Guantanamo, arguing pointedly that the only standing charges against them were those he had filed in Spain.

Garzón has also been unflinching in his criticism of the Iraq war and the support it received from Spain’s conservative prime minister, José María Aznar. In open letters to Spanish newspapers and at a massive demonstration in downtown Madrid, Garzón decried the war as illegal, unnecessary, and almost certainly counterproductive in the pursuit of a more pro-Western Middle East. He has been especially dismissive of the American attempt to link the crimes of Saddam Hussein with those of Al Qaeda, citing several terrorism investigations that suggested otherwise. Speaking out was not without risk: Garzón was threatened with formal sanction by the judicial authorities for his remarks about Aznar.

Yet unlike most of the Europeans who now criticize American policies abroad, Garzón does so from a well-dug trench in the antiterror fight. Working closely with foreign police and intelligence agencies, including the FBI, Garzón has tracked Al Qaeda operatives for years. Since September 11, he has prosecuted a network of radical Islamists in Spain that he accuses of having assisted in the attacks. Over the last decade, he has also played a central role in Spain’s struggle against terrorism in the Basque region, leading some of the most important prosecutions of ETA, the separatist group founded in 1959 as Euskadi Ta Askatasuna, or “Basque Homeland and Freedom.” Garzón also battled his own government to expose the role of Spanish security officials behind assassination squads that hunted down Basque separatists in the mid-1980s.

Outside Spain, Garzón is best known for his attempt to extradite Pinochet while the aging general was visiting London in 1998. The prosecution took bold advantage of a 1985 Spanish law that established the courts’ jurisdiction in crimes against Spaniards even when they occur on foreign soil. But it ran into determined opposition from the Aznar administration, and it ultimately failed when Britain released the 84-year-old Pinochet for health reasons after 16 months of house arrest. Still, the case served notice to many of the world’s tyrants that their impunity had been circumscribed, and it opened the way to other prosecutions for crimes against humanity in Europe and Africa. It also made Garzón a hero to the international human-rights movement.

He has burnished that status by pressing his inquiry into Operation Condor, the plan by which South American military regimes collaborated in the 1970s and early ’80s to eliminate their suspected enemies. Last June, he won the landmark extradition from Mexico of a retired Argentine naval officer, Ricardo Miguel Cavallo, on charges that he tortured Spanish citizens, among others, during Argentina’s “Dirty War” on subversion. (It was the first time in which one country had extradited a suspect to another country to face trial for crimes committed in a third.) In July, at Garzón’s request, the Argentine government arrested 38 more former military officers. It released about half of them after the Aznar administration voided the order.

Over the last year or so, however, Garzón has begun to disappoint some of those who embraced him as a liberal champion in the war on terror. To the disquiet of civil libertarians (but now with Prime Minister Aznar very much on his side), he has steadily widened the fight against Basque separatists, targeting the teenage shock troops who intimidate moderate politicians, the relatives who raise money for ETA prisoners, and the strident Basque-language newspapers, among others. Garzón has also led a judicial effort to outlaw the radical political party Batasuna—a fixture of Basque politics that held a seat on the European Parliament—on the grounds that it serves as ETA’s political wing.

To Garzón’s mind, he is simply reaching as far as he legally can to dismantle a complex terrorist network. Should he overreach, he says, there is more than enough judicial recourse for his opponents. Already, he notes, the Batasuna ban has been the subject of appeals before the Spanish Supreme Court, the Constitutional Court, and the European Court of Human Rights. Yet even many Basque moderates are unconvinced; they count Garzón among the hardest of hardliners.

The apparent contradictions in Garzón’s approach are a favorite subject among his Spanish critics. They see a hunger for big, high-profile investigations—and the headlines they bring—as the one constant in his case file. “That desire to win spectacular cases—that is more powerful in him than any other motivation,” said Juan Alberto Belloch, a former Spanish justice minister who has battled with Garzón. “He needs attention.”

It is without question a remarkable case file. A sampling from the last couple of years includes a request to question Henry Kissinger about American support for Pinochet’s repression; a sweeping corruption investigation into Spain’s second-largest bank, BBVA; and an attempt to prosecute Italian prime minister Silvio Berlusconi for tax evasion and fraud at a Spanish television station he partly owns. Not all of these efforts have been successful: The U.S. State Department rejected Garzón’s Kissinger petition, and Spain’s Constitutional Court suspended the Berlusconi case—at least as long as he remains prime minister. A handful of executives still face charges in the BBVA case. Still, Garzón professes not to worry that his rulings are not infrequently pared back by higher courts. Under Spanish criminal law, a magistrate like himself functions like an American prosecutor and grand jury: He investigates a police accusation or citizen complaint but also weighs exculpatory evidence before bringing indictments. He then reports to more senior judges, who decide whether to bring the case to trial.

“People in Spain criticize him a lot for being vain, but so what?” said Garzón’s friend José Antonio Martínez Soler, a newspaper editor in Madrid. “He’s not vain in a petty way. He wants to make history. He is someone who takes risks. People admire that.”

Yet Garzón remains an enigmatic figure even to his compatriots. And he seems to like it that way. His investigations are often conducted in secret. He almost never discusses his cases publicly and rarely grants formal interviews. For a man who seems to enjoy his prominence, he is oddly shy. “Venga,” he says in Spanish, smiling impatiently, at the beginning of one of several long conversations for this story. “Come on. What do you need to know?”

GARZóN’S RISE is a measure of the distance that Spain has traveled since the death of the dictator Francisco Franco in 1975. Today, it passes without note that the judge investigating South America’s former tyrants once fought police riot squads as a student protester. But the old Spain weighed heavily in Torres, the small, hardscrabble town in Andalucia where Garzón grew up. Into the 1960s, it was a place almost untouched by foreign movies or television, where the authority of the Catholic Church and the Guardia Civil were absolute. Garzón attended a Catholic seminary, and he learned about politics from a favorite uncle, a well-spoken farmer who fought with the Republican Army and had been sentenced to death as the civil war ended in 1939.

“His sentence was commuted,” Garzón told me. “But from that moment on, and throughout the 40 years of Franco, he was constantly watched and persecuted—even about the most insignificant things. I saw that persecution from the time I was a child.”

By the time he entered the University of Sevilla in 1973, Garzón was already determined to become a judge. It was an unusual ambition in a country where the judiciary had often served as an arm of Franco’s repression. But if Garzón was serious, he wasn’t dull. Law-school friends remember a guy who loved flamenco and rock and roll and hated to leave a good party. He studied obsessively, often reading through the night while pulling the late shift at a gas station where his father worked. He graduated at the top of his class and married his girlfriend of eight years, Rosario Molina. He then moved his young wife to a quiet town near the Portuguese border to begin his career as a local judge.

Though Garzón rose quickly through the ranks, he showed little talent for the intricate politics of the post-Franco judiciary. Taking over at 30 as the inspector for the courts in Andalucia, he found evidence of corruption among prominent court officials in the coastal resort of Marbella and wrote a confidential report urging further inquiry. When his superiors shelved the case instead, Garzón was ready to quit. “I was just pushing paper,” he said. “I said to myself, ‘I’m not doing anything here.'”

Then, a couple of seats came open on the high court in Madrid, and at 32, Garzón qualified for one of the openings. They were not especially coveted posts; the cases that would soon fill the Audiencia’s docket—drug trafficking, financial crimes, corruption—were just starting to command public attention. And terrorism was a confounding mainstay: Despite Spain’s transition to democracy and the provision of autonomy powers to the Basque region under the 1978 constitution, ETA only escalated its attacks. Even the 1982 election of Prime Minister Felipe González, a young, charismatic Socialist, had done nothing to slow the separatists’ violent campaign.

The case that would define many of Garzón’s views about fighting terrorism was on his desk when he joined the high court in 1988. “That’s where the story began,” he told me. The investigation involved a mysterious four-year wave of bombings, shootings, and kidnappings in southern France and northern Spain in which 27 people had been killed, most of them Basque militants. The Spanish authorities had been notably slow to investigate. But the French eventually issued international warrants for the arrest of two Spanish police officials—a superintendent and his deputy.

Further evidence soon emerged tying the Spanish security forces to the rightist assassination squads that came to be known as the Grupos Anti-terroristas de Liberación, or GAL. But when Garzón sought information on secret government accounts linked to GAL, he found himself blocked. Prime Minister González maintained that the release of such information would compromise national security. Undeterred, Garzón ordered the two police officials arrested.

“Do you understand what you have set in motion here?” one of Garzón’s astonished friends, Antonio Navalón Sánchez, recalled having asked him at the time. Garzón answered directly: “It’s very simple: They either have to change the law so that they can kill people, or they have to respect it.”

Navalón, a media executive sympathetic to the González regime, didn’t know whether to be impressed by Garzón or afraid for his life. “He is kind of a Calvinist about the law,” Navalón said. “Once he comes to his conclusion, nothing stops him.”

As Garzón dug deeper, Socialist officials and even some judges began to complain that he was out of control. Belloch, the rival jurist, called him “a prosecutor in judicial robes.” But Garzón pursued ETA militants with equal passion. He pushed for information—sifting leads, suggesting theories. He built ties to key police investigators and prosecutors, and they quietly steered him cases that would otherwise have been distributed at random among the high court judges.

Garzón also began to display what was—at least by the standards of the Spanish judiciary—an unusual flair for the dramatic. He loved working with the cops and seemed always to be on the scene when they made a big drug bust or rescued a kidnapped businessman. Before important hearings, he told me, he sometimes watched a worn videotape of the 1969 film Z, Costa-Gavras’ thriller about a courageous magistrate’s inquiry into the murder of a liberal politician in Greece. (Garzón’s wife, Rosario, later told me he also saw Gladiator and The Fellowship of the Ring four or five times each.) Some compared Garzón to headline-grabbing American prosecutors like Louis Freeh and Rudolph Giuliani. But Garzón had a different model: Giovanni Falcone, the crusading Italian magistrate whose murder by the Mafia in 1992 helped to turn Italians decisively against the Cosa Nostra and its political allies.

By the early 1990s, Garzón’s high-profile investigations had made him one of the most popular public figures in Spain. At the same time, Prime Minister González and his Socialists were in a tailspin, with complaints about corruption growing louder. Promising reform, González wooed Garzón to a new, high-level post to combat drug trafficking and corruption. Many Spaniards were aghast that he would take the job, given the suggestion of government involvement in the GAL case, but he proved to be just the electoral weapon that the Socialists needed. In June 1993, González won a stunning fourth term. But the prime minister’s spell on Garzón wore off quickly. Calls to González’s office went unreturned; the anti-corruption effort went nowhere. Garzón resigned after less than a year, telling a news conference, “González used me like a puppet.”

Ten years later, Garzón is still touchy about his brief political career. “I don’t regret it—I never regret things,” he said. I pressed him a bit, asking whether he had been naive in dealing with González. “I’ve always thought that naivete is not a defect—if by naivete you mean that you think you can change things,” he said. “My sin was hubris: to think that one person could have really gotten something done there.”

Garzón returned to the high court with what one of his closest friends of that period, Ventura Pérez Mariño, remembered as “a sense of absolute failure.” Many observers felt he shouldn’t go back at all, given the prospect that he might be called upon to judge former government colleagues. Such a conflict arose almost immediately: Evidence in a new GAL case pointed to the involvement of senior government officials—perhaps even González himself—in the kidnapping of a suspected ETA militant.

Garzón’s pursuit of the matter became the stuff of Socialist nightmares. In short order, he won indictments against half a dozen current and former officials. In January 1995, González went on national television to deny any involvement in the case. But in 1996, Spanish voters delivered their own verdict, ousting the Socialists in favor of Aznar and his conservative Popular Party. (By 1998, the Supreme Court had convicted all of the major figures Garzón had indicted. It later discounted the evidence against González and reprimanded Garzón for implicating the prime minister.)

THE GREAT IRONY of the GAL cases is that by uncovering the government’s support for the death squads, the belief among many Basque separatists that they remained under siege, democracy or not, was validated. I told Garzón of meeting young Basque radicals who had talked late into the night about the “repression” they suffer at Spanish hands. Most of them had never known Franco’s rule. They had grown up in a prosperous, autonomous region with its own parliament and police force; they learned Euskera, the Basque language, in public schools. But the GAL crimes were clearly an open wound for them. They were also, Garzón admitted, just the sort of kids that ETA recruits to the underground.

The political dynamics of the global war on terrorism are not dissimilar, Garzón argued. “To fight fire with fire is always going to be catastrophic,” he said. “Very simply, that kind of action puts you on the same level as the terrorists. Although, really, you are in an even more perverse place because you are undermining the democratic system and you are getting absolutely nowhere in the process. Eventually, you will be held accountable. And that will give the terrorists a weapon they would not otherwise have.”

Garzón bristles at the notion that he might be advocating a “softer” fight against terrorism. “I am not some sort of Candide, or some kind of ultrapacifist who believes that everything can be solved without the use of force,” he went on. “It may make sense to use force—within the law of the land and according to the seriousness of the injury that you are trying to avoid or repair. But all over Europe—in England, in Germany, in Italy, in Spain—we are arresting people in terrorism cases and fighting terrorism within the law. I’m not so naive as to think we judges will do away with terrorism by ourselves. But together with good police work, with good intelligence, there is a lot that we can do.”

Garzón advocates a longer view of the struggle, one that more explicitly acknowledges the interdependence of allies. He said he understood when, in the immediate aftermath of the September 11 attacks, the United States demanded intelligence help from its allies while providing little in return. But he said that, to this day, his formal requests for information are typically met with silence from the Justice Department.

The United States’ treatment of terrorist suspects has created a problem that transcends the battle for Islamic hearts and minds, Garzón asserts. The legal assault on a global terrorist infrastructure like Al Qaeda’s is by definition an international enterprise, he says, one that may be crippled if the United States thinks only of the trials it intends to bring. “We cannot use anything that might be obtained in Guantanamo, for instance, because the prisoners there are not being given due process. So as far as any democratic state in Europe or anywhere else is concerned, that evidence is useless.”

To those who see the latest round of the U.S.-European conflict as having originated in a failure of diplomacy before the Iraq war, Garzón also offers a more pessimistic view. The dispute, he said, is in large part over two different visions of the struggle against terrorism: an American “military strategy,” in which intelligence is gathered for so-called direct action against terrorists, and a “civil approach,” in which evidence is collected with a view toward the legal prosecution of terrorist crimes. The two need not be mutually exclusive, Garzón says, but the civil approach cannot succeed, even in the long term, unless international legal standards are upheld now.

As Garzón spoke, a judge from another court knocked at the of-fice door to wish him well. The day before, the Basque provincial government had filed a motion to force Garzón off the case against the Batasuna party, arguing that he had shown bias. (The suit was quickly dismissed.) Two more colleagues stopped by in the next half-hour, wondering how he was getting on. In late 2002, Garzón suffered a facial paralysis that doctors linked to exhaustion. Even some of his friends have urged him to be more selective about the cases he chooses. But not all of them are worried.

“What makes him happiest is to be mixed up in the middle of things like this,” said Manuel Medina, who has known Garzón since his early days as a judge. “He’s like a bullfighter who thinks, ‘I am happy because I am going to die in a bullring.'”

Garzón’s wife, Rosario, said she understood her husband differently. “He might feel fear; I have felt it,” she said, alluding to the terrorists he has taken on. “I think they will come after him. If they can, they will try to eliminate Baltasar. Everyone knows that—they kill everyone they can.” Since the family moved to Madrid, Rosario said, their well-guarded home has been broken into at least twice, with warnings left behind. She revealed this almost matter-of-factly, in an interview to which she arrived alone. Then she went on: “But what sense can your life have if you spend it hiding or running away? This is history. He has to do this.”