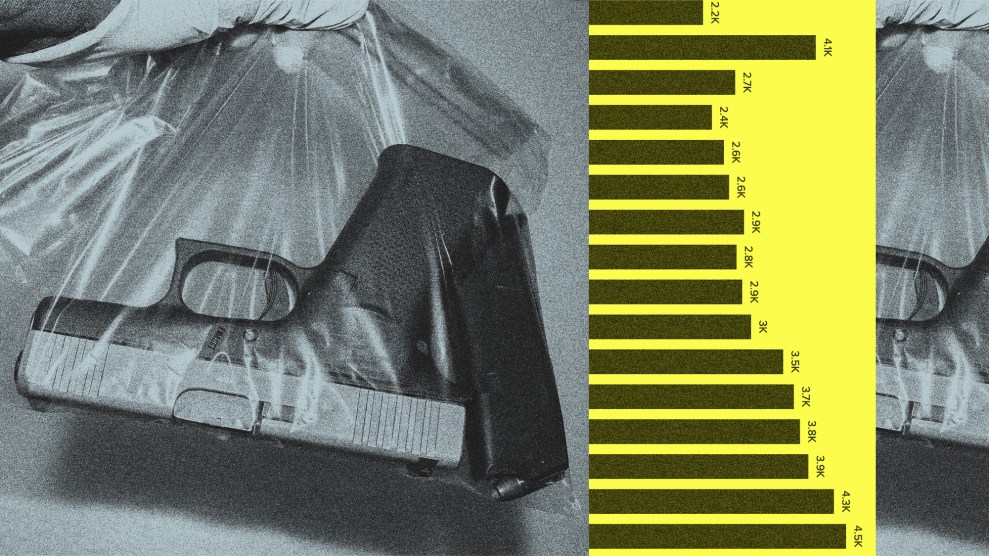

For critics of the Iraq occupation, the running tally of American deaths in Iraq, now in the high 300s, has become an index of the failure of the Bush administration’s postwar policy. August 26, the day the number of soldiers killed since the president declared an end to major combat surpassed the number killed in the war, was a pivot-point in the U.S. campaign, after which it was possible to talk of “failure” in Iraq.

It isn’t minimizing the seriousness of these figures, nor the real anguish they represent for hundreds of families, to note that the focus on fatalities has obscured a significant, and much larger, number — the toll of soldiers injured in Iraq, many of them gravely.

More than 2000 soldiers are reported injured since hostilities began in March. And with the number of daily attacks on U.S. soldiers at more than 30, and rising, the figure is only going to grow. But the U.S military hasn’t been forthcoming with the numbers of wounded, and the media has tended to underreport them:

In an article for The New Republic, Lawrence Kaplan tries to explain the comparative neglect of the wounded:

“The near-invisibility of the wounded has several sources. The media has always treated combat deaths as the most reliable measure of battlefield progress, while for its part the administration has been reluctant to divulge the full number of wounded.”

An article in Time notes:

“Soldiers have been wounded in war since the beginning of time — a fact that armies never like advertising. The Pentagon, which makes terse announcements when U.S. soldiers die in combat in Iraq, doesn’t inform the public about those who have been wounded or release month-by-month injury counts. The wounded are mentioned only when some other soldier has been killed in the same attack.”

American soldiers, thanks to improvements in technology, have a better chance of surviving their wounds than any soldiers in history. John Greenwood, chief of the office of medical history, in a piece in the Army Times, said that of the soldiers injured in Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom, only 1.6 percent have died of their wounds, less than half the 3.68 death rate for wounded soldiers in Vietnam.

There’s a downside, of course, which is that soldiers, because they survive, have to live with worse injuries than any soldiers in history. Again, the Time article:

“Better protection, faster evacuation and improved medical techniques at the edge of combat have dramatically reduced battlefield mortality. At the same time, although body armor and wound-sealing potions have made it less likely that soldiers will be killed in battle, they have also increased the likelihood of certain kinds of injuries, especially amputation, because a soldier’s extremities remain vulnerable to the kind of homemade munitions the Iraqis are routinely deploying. The Iraqis lack the air power and artillery that can easily kill, but the weapons they are using — RPGs, car bombs and improvised explosive devices — have increased the ranks of the wounded. And these wounded seem to be threatening the morale of the soldiers left behind. While the Air Force has flown 1,513 battle casualties from the Iraqi theater, 9,341 have been flown out for other health reasons, including mental stress.”

As Captain Todd Farrell, a helicopter pilot, tells Time, “People say, ‘Well, he didn’t die. But a lot of these guys have an arm blown off or their leg blown off below the femur. Their lives are still going to suck.” About 20% of the injured in Iraq have suffered severe brain injuriesÑalthough, Major General Kevin C. Kiley, commanding general of the North Atlantic Regional Medical Command, says in an Oct. 16 Boston Globe article that as many as 70% of those wounded suffered potential for a brain injury.

And improvements in technology do no good if injured soldiers don’t have access to it. At least one report points to a shortage of medical help for the wounded. At the end of October, United Press International and a veterans rights group reported that hundreds of National Guard and Army Reserve soldiers were holed up in dismal barracks in Fort Stewart, Georgia, awaiting medical care. Some soldiers had been waiting for medical care for months in the sub-standard housing, which lacked indoor plumbing or air conditioning. Tompaine.com reports:

“They’re being treated like dogs,” is how one officer who didn’t want his name used put it, speaking to TomPaine.com before the UPI story broke. “There is not a smile on this sector of the post. I have never seen as many sad people in one place in all my life. …

“I’ve been in [the military] for 30 years and never thought the Army would turn on its own like this,” said First Sgt. Gerry Mosley, of the National Guard’s 296th Transportation Company from Brookhaven, Miss. “I am not in a case by myself. They are telling you it’s going to be four to six months if you’re going through a medical evaluation.”

As part of its P.R. campaign to hype progress in Iraq, the government does its best to downplay fatalities. President Bush, as is well known, ordered that the coffins of dead soldiers be hidden from the view of the press, lest the demoralizing images undercut confidence in his administration.

But similar restrictions apply to coverage of the wounded. As Senator Patrick Leahy of Vermont, co-chair of the 83-member U.S. Senate National Guard Caucus, said recently on the Senate floor, “The wounded are brought back after midnight, making sure the press does not see the planes coming in with the wounded.”