Photo Illustration: Jonas Bendiksen

Old-timers recall that when they were children and the town of Lackawanna, just outside Buffalo, New York, was home to the world’s largest steel mill, some 35 languages were spoken in the First Ward. And perhaps it’s because of that long memory that when an abandoned Ukrainian Orthodox church was reborn as a mosque in 1975 and the muezzin’s call to prayer carried out to the streets via loudspeaker, people who couldn’t understand Arabic, and maybe disliked it, accommodated to it as yet another of history’s additions to the neighborhood. In the years that followed there would be mostly subtractions, of jobs and attention, as steelmaking stopped and the people who stayed on tried to negotiate the transit from steel culture to something else.

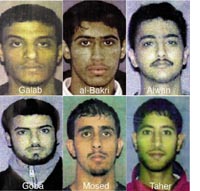

That journey is neither coherent nor complete, and ordinarily wouldn’t single out Lackawanna for special notice from all the towns in all the once-prosperous industrial regions of America. But the “ordinary” has been undergoing some redefinition lately. Last September six young men here were arrested, charged with providing “material support and resources” to terrorists, and labeled a “sleeper cell.” Who they are, and what combination of desire, curiosity, or bad luck led them on their particular journey to Pakistan for a religious pilgrimage and thence allegedly to an Al Qaeda training camp in Afghanistan, is known only in shards. Small-town suspicion has turned to silence these days. On a recent night outside the mosque, a group of “Arabian” boys in oversize warm-up pants and hoodies asked a stranger why she had stopped, what she was looking at, why she wasn’t getting on her way, and then adjourned wordlessly to the parking lot for a little touch football, as the prayerful chant floated over satellite dishes on the weathered frame houses, through the narrow paths of the low brick housing project, across the lawns and broad driveways of new suburban-style homes and the empty lots of the used-to-be.

“We are living in an age of fire, and we must be very careful,” Ahmed Jamil said later, explaining why his 18-year-old daughter and her schoolmates had not kept their appointment to talk about growing up in the second-largest Yemeni American community in the country. On “the day of doom,” Friday the 13th of last September, Jamil had been working at the house of his son’s brother-in-law, 26-year-old Yahya Goba, when he heard a knock at the front and, from the side door behind him, footsteps. Jamil recalls backing into a corner as FBI agents and police, guns drawn, searched the place. A few blocks away, at the Yemen Soccer Field, one of the Lackawanna High School teams was finishing practice when seven FBI cars came by and a police officer called over the coach and soccer club director, Abdulsalam Noman, for a word. Noman has coached five of the six suspects, and at the time of this inquiry, four of them—Shafal Mosed (goalie, 24), Mukhtar al-Bakri (offense, 22), Faysal Galab (defense, 26), and Noman’s nephew Yasein Taher (offense and defense, 24)—were still in the adult weekend league. The fifth, Sahim Alwan (midfield, 29), hadn’t played since high school. Noman says that within 20 minutes the First Ward “was like a war zone.”

“A law-enforcement circus, a media circus” is how one county police officer described what ensued, and the Yemenis, an intensely private community of about 3,500 out of a population of 19,000, became even more so. Today, down Lackawanna’s main artery, Ridge Road, and across the railroad tracks that separate the mainly brown and black First Ward from the whiter and incrementally better-off Second, Third, and Fourth wards, other townsfolk say they hardly see the Arabians anymore. (“We always called them Arabians,” Ruth Cullen, a senior aide at the Lackawanna Public Library, remarked. “Of course, they’ve been called other names, very vulgar names.”) Arabian regulars at Cup of Joe’s diner stopped coming, according to the proprietor, Joe Paolini. “That’s the saddest thing,” he said, “that people feel scared.” Down the street, a storefront dealing in security gear called The swat Institute sold every shotgun off the wall after the arrests, according to firearms instructor Joseph Haley, and requests for pistol permits and shooting lessons spiked.

Outside the mosque after prayers one late November afternoon, a man who gave his name only as Abdul told me he initially talked with reporters only to see his words misquoted or miscontextualized, so he would have nothing more to say, nor would the imam, whose imperfect English might be misconstrued. The community, the families, had been advised to do the same. “Talk to our leaders,” he said. On December 17, one he recommended, Mohammad Albanna—vice president of the American Muslim Council, member of the Yemenite American Merchants Association, owner of a major cigarette and candy distributorship in Buffalo, frequent presence at school board and City Council meetings, a man who did not keep quiet after the arrests but who calmly spoke of democratic rights and, if asked, of his concerns about U.S. foreign policy—was himself arrested. At 8 a.m., as children headed for school, police descended upon the First Ward again, closing streets, searching homes, and handcuffing Albanna and two relatives for doing what immigrants from poor countries do every day: sending money home. Not to terrorists, prosecutors admit, but not in small amounts or with the proper license either, and now the Yemenis of Lackawanna have had one more lesson in the wisdom of silence and invisibility.

We have become strangely accustomed to this silence. Since September 11, at least 1,200 immigrants have been held in detention without charge; at least 15 U.S. citizens are currently incarcerated on terrorism-related claims. No defense lawyer has seized the spotlight. No intimate has insistently cried out, This is my son, my brother, my husband, my friend; these are his loves, his foibles, the neat and messy stuff of his complicated human life. It is all perfectly understandable, and perfectly opportune for police agents and prosecutors. Americans are busy people; who can keep track of so many disembodied, dehistoricized “detainees,” “enemy combatants,” “American Taliban,” and “terror suspects”?

The Lackawanna “terror cell” presents a special twist, because silence, indeed a “conspiracy of silence,” is central to the government’s case so far. Alwan, al-Bakri, Galab, Goba, Mosed, and Taher, all but one American-born, are accused of no violent act or plot in the usual understanding of those words. No cache of arms has been found, no plans for future malevolence. They are charged under the Antiterrorism and Effective Death Penalty Act. Conviction could get them 15 years in prison, a $250,000 fine, or both. There are, or were, two co-defendants. One is Jaber Elbaneh, a Lackawannan whose fugitive status likely prompted the surveillance of his uncle Mohammad Albanna, who is also related to two of the men arrested in September. The other is Kamal Derwish, assassinated on November 3, when a U.S. Predator drone fired a missile at a car in Yemen, killing everyone inside, including an alleged high-ranking Al Qaeda figure. Derwish, an American who lived briefly in Lackawanna, is said to have suggested and arranged the other men’s journey to Afghanistan. Whatever information he had about them, incriminating or exculpatory, perished with him.

According to the government, in the spring of 2001, the “Lackawanna Six,” as they are being called, plus Elbaneh, traveled to Pakistan for a spiritual retreat under the auspices of Tablighi Jamaat, a Pakistani missionary group that, depending on who is talking, is either irresponsibly apolitical, oppressively dogmatic, mystically centered on good works, or a breeder reactor for political extremists. In any case, it has never been on any U.S. terror list. The government does not say the men left Lackawanna intending to go to Afghanistan, or that they are members of Al Qaeda. It says that after a brief sojourn in Pakistan, where they encountered Derwish, they traveled to Kandahar, staying in guest houses where the talk was all of jihad and martyrdom. From there, it’s alleged, they went to a camp called Al Farooq, where they trained in groups of 20, assembled and disassembled rifles, learned to shoot and climb mountains, watched explosives go off, slept in tents, wore uniforms every day but Friday, used aliases and passwords, refrained from small talk and self-revelation. One day they saw Osama bin Laden, who made a speech “espousing anti-United States and anti-Israeli sentiments.”

Then they returned to Lackawanna and told no one of their experiences. This was the summer of 2001. After the attacks of September 11, they still said nothing. “While the defendants have roots in the Yemeni community of Lackawanna,” the government argues, by their silence “the defendants failed to demonstrate [their] ties to the American community, let alone their allegiance to the American community.”

Sahim Alwan, who eventually supplied much of the above information to the FBI, told agents that the camp was frightening, that he cried and feigned an ankle injury so as to be released after 10 days. The rest are said to have stayed on a few weeks. The government insists that the men could have declined the Afghan trip and didn’t, could have left the guest houses en route and didn’t, were free to leave the training camp and didn’t. Alwan maintains that the guest houses were in desolate country where they had no bearings or friends and that one couldn’t leave the camp freely. A friend of Galab told the New York Times that after the trip, “he told me, ‘No, man, we were at this rotten hotel and we were misguided.'” According to coach Noman, Taher returned saying, “Uncle, I appreciate this country more than any other time.” He said they slept on dirty mattresses, had bad food, and, finally, “it was a waste of time; we didn’t learn anything.”

At various times over the year or so that elapsed between their return from Pakistan and their arrest, the six were interviewed by the FBI. Only Alwan and al-Bakri, who was picked up in Bahrain the day after his wedding and interrogated there by U.S. agents on September 11, 2002, admitted being in Afghanistan. Detention hearings in U.S. District Court last fall revolved around whether the six were dangerous if they had no violent history, had committed no violent act, and were the subject of no “clear and convincing evidence” showing “they were preparing, planning, or committing acts of harm,” in the words of Judge Kenneth Schroeder. The judge was troubled. If the men had been to the camp and denied it to federal agents, they weren’t honest, but neither were they under arrest at the time they were questioned. Silence, moreover, not only is not a crime; it’s a right. Yet the federal prosecutor, William Hochul Jr., said it “should be used against” the defendants. However repellent the camp or bin Laden’s speech, Judge Schroeder noted, there are no laws requiring citizens to report attendance at such things, to which Hochul responded, “It’s more of an obligation, I suppose, if you’re an American citizen, to the citizenry, or to humanity.”

The judge wondered, “Is the government asking me to speculate some sort of potential act of violence or danger?” Where, he asked, is the evidence? In a bit of burden shifting, the prosecution essentially said, There is no evidence because the defendants have not provided it. They “by themselves have put the court in this box,” Hochul said. “They’re the ones who went to the Al Qaeda training camp…but who didn’t tell anybody about it.” And given that the government charges that they “knowingly, intentionally, willfully supported this group…this absence of clear evidence or clear indications is somewhat ominous. Again,” he said, “we’re projecting against this conspiracy of silence.”

Politics trumped skepticism in the end: The judge found that no conditions of pretrial release could protect America from five of the men. Only Alwan was granted bail: a $600,000 bond, plus house arrest, GPS satellite monitoring and phone taps, for which he must also pay. Some of the other defendants offered to submit to similar surveillance regimens. Galab proposed round-the-clock video monitoring in all but the bathroom and bedroom of his home. According to the appeal filed by his lawyer, Joe LaTona, “the only response prosecutors had to Mr. Galab’s offer…was that it would not enable the government to know what was in Mr. Galab’s mind.”

On January 10, Galab pleaded guilty to lesser charges, admitting he’d had transactions with Al Qaeda—to wit, he paid for a uniform, stood guard duty at the camp, and received the aforementioned training. He agreed to a 10-year sentence, which could be reduced to seven. His relatives say he was cutting his losses. The others may try to do the same. At issue in the case against them is what constitutes providing material support and resources to terrorists. The U.S. Attorney’s Manual, setting conditions for prosecution, says persons must be “acting as full- or part-time employees or otherwise taking orders from the entity,” or they must be providing personnel or training. But from the beginning, the government has made no distinction between “receiving” and “providing” in this case; as Hochul argued, “You can provide personnel by way of yourself.” One’s body is thus the material resource; one’s support evidenced just by having been at the camp. Under such a reading of the law, what the men actually did there, with what intentions, becomes irrelevant.

Yet the deepest questions revolve precisely around the men’s intentions. Galab’s agreement is silent there. If they really were keening to be martyrs in Al Qaeda’s marquee operations and then sat around Lackawanna awaiting orders, their story is more pathetic than frightening. Al Farooq, according to government testimony in the Africa embassy bombing cases, was a boot camp to supply infantry for the then-U.S.-funded Taliban in their war against the Northern Alliance. John Walker Lindh also learned how to shoot and climb mountains there, and arrest is probably what saved him from grimy, anonymous death. Al Farooq, according to a terror-policy watcher who preferred anonymity, was “for the guys who were gonna schlepp, not for terrorists. You could move up to the terror camps, but there you were basically cannon fodder.”

In his 1991 high school yearbook, Sahim Alwan thanked Allah, his parents, his social gang, the Arabian Posse, and, despite long-standing black-Arabian tensions in the region, fondly remembered a hangout in the heart of Buffalo’s black section. Galab, Mosed, and Taher, who as teenagers spray-painted their clothes with the insignia of their crew, the Arabian Knights, participated in the hip-hop mix that defines the First Ward as much as the sight of a veiled woman or the men headed for prayer. Taher was voted “friendliest” by his graduating class in 1996. Like so many Lackawanna High School graduates, the six did not go on to college (though Mosed was in community college at the time of his arrest), and their employment was uneven. Galab co-owns a Sunoco station. Taher, Goba, and al-Bakri were out of work or casually employed. Alwan, who worked with underprivileged kids, was an emerging local leader, attending meetings with the FBI after 9/11 on the dual need to protect community and country.

It’s said that the men began focusing on matters of faith as part of a changed life strategy once they married, had children, or contemplated same. They grew beards, prayed, stopped drinking, and discoursed on the finer points of Islam. As some of them still may have gambled, followed the Buffalo Bills obsessively, ate pizza and chicken wings, and, in Taher’s case, had a white non-Muslim wife, they were perfect objects for the attentions of Tablighi Jamaat, which urges wavering Muslims to Pakistan for a tour of humility and renewal. (Searching for meaning in Marin County, Walker Lindh started out on a Tablighi-motivated Magical Mystery Tour as well.) From some of their homes, police confiscated a jumble of jihadi tapes and literature. To prosecutors, those prove extremist commitment. To Taher’s attorney, Rodney Personius, possession of such materials—if they were even perused—is “more consistent with a rational inquiry into a controversial interpretation of the Islamic faith.” Before his own arrest, Mohammad Albanna said, “A lot of people wrestle with this question of identity. I think these individuals wanted to know more about what it meant to be a true Muslim in a non-Muslim society.” It seems, he said, they were naive.

Identity was once an easy thing for Lackawanna. The Lackawanna Steel Company built the town, named it, and underwrote everything down to the school supplies. Via employment, it instigated mass migrations to the area and, via pollution, family mobility out of the First Ward and into the stretches that now fill out the town proper. Progress didn’t so much mean your children wouldn’t be steelworkers as that you could live where you didn’t have to hang the wash in the attic to spare it from soot. With time, if you were white, it also meant your children spoke only English and had no more than a sentimental attachment to old-country culture. This was the working class when that term still signified something potent and distinct. In 1903, when the steel plant opened, it was called the “Eighth Wonder of the World.” At its height it employed 22,000. In 1982, when its successor, Bethlehem Steel, announced the shutdown, a worker memorably remarked, “Might as well have pants without pockets.” On a sunny day in 1995 the basic oxygen furnace, once the finest in the world, was dynamited to dust. It took five seconds.

More than 8,000 people moved away from Lackawanna between 1970 and 1990. A host of smaller steelmakers and industries went too, some hiring former metalworkers as minimum-wage sweepers or security guards until the demolition crews arrived. About 15 years ago an ethnography of white students at Lackawanna High found that the boys had no distinct identity. They defined themselves by what they were not: not black, not girls, not Hispanic, not Arabian. Abdulsalam Noman nodded hearing this.

“I looked at the other communities that came before us,” he said. Down the street from the Yemenite Benevolent Association, the Polish club, Dom Polski, is shuttered; the Spanish-American Welfare Society, a relic. “The Lackawanna Arab community kept us together—the language, the culture, and the religion together. If we take that apart, we’re going to lose it.” And “when you lose your culture, basically there is no culture for you.”

Because of culture or familiarity with dislocation or both, the life and death of steel does not weigh heavy in the conversation of Yemenis as it does among older-line groups. Yemenis didn’t immigrate en masse to Lackawanna until the 1940s and ’50s, when Ahmed Jamil arrived. He was 17, a farm boy, barely literate in Arabic, when Bethlehem hired him. By 1957, he says, there were about 300 Yemenis in town, all men. They shared housing and living expenses, and remitted money home. For self-help they started the Benevolent Association, and for distraction, played cards or disported in the gin mills, clubs, and theaters that then lined Ridge Road. Eased immigration restrictions allowed families to come in the 1960s and ’70s.

“That’s when we realized this is our country,” Jamil says. “We have to share its blessings and its responsibility. We have to feel more like Americans than Arabs.” As industry hemorrhaged jobs, many Yemenis looked ahead, pooled their savings and expenses, lent to each other without interest, worked the system, and bought up grocery stores. At the same time, people rediscovered religion. In the early days, Jamil recalled, “I was American Number One. Everything wrong is right in my eyes—womanizing, other interests. Everything is good as long as there is indulgence. Until 1977 I wasn’t practicing Islam at all.” Then a Black Muslim asked him for scriptural guidance, and “I didn’t know. That put me square to know about Islam, not only about Islam but about God—Arab, Christian, Jewish.”

He says the younger generation is making up for what its elders neglected in piety, but just beyond the mosque on Wilkesbarre Avenue one finds a cultural fluidity that such elders don’t discuss. “Assalam Allykum, Allykum Assalam!” a twentysomething Arabian looking more Sean John than imam shouted out as he entered the Liberty Food Mart there one Friday. A sign in the store advises customers to pay and be on their way, but on this cold, rainy afternoon the counterman, called Mason, was going easy. As Muslims they’re not supposed to be near alcohol, pork, or gambling either, a young Arabian noted, but “you gotta serve the people.” And Mason, 20, slim, wearing a baggy white T-shirt and a bandanna on his head, treated everyone with familylike regard: old blacks and Puerto Ricans, hands gripping lottery picks; kids cramming chips, older sisters slapping the cash for cigarettes or a strawberry Dutch Master; young brothers decked out ghetto fabulous, middle-aged guys in Bills sweats, black ladies planning weekend dos—give them a Phillies Blunt, a six-pack, those almost-real hair braids; white girls, moony and plain or crudely sassy, finding excuses to flirt with the Arabians. It was Ramadan, but one Arabian was eating a sandwich, another smoking fitfully till sundown; and the talk, English to Arabic, ricocheted around the jobs they had to get to, the car that wasn’t running, the ride that might be coming, the booty got or not got, the pot that should be legal, the baby, baby momma, debt to family, and, just in squibs, the suspects/friends in jail.

“Sameer Alwan, Sameer Alwan,” one called out to a kid by the counter. “Look, he doesn’t even turn. That’s Sahim’s brother. Hey, man, how’s the bail going?” Sameer looked scared, though everyone there knew or was related to the suspects. “The families are freaking,” another allowed, his own included. He’s not into the Islamic stuff, he said, though he’s teaching his son the basics, certainly the language. He and the boy’s mother aren’t married, but the families “are cool with it”; she’s teaching the child about Irish Catholicism. A crew of African Americans rushed in, his ride. After midnight they’d be at Buffalo clubs like The Groove and Utopia, creeping home at 5 or 6 a.m. Best not to touch that subject with the older folks; “I keep it on the down-low,” another Arabian said.

Earlier I’d been told about a teenage girl who wore the hijab and outwardly practiced the faith while secretly piercing her navel and envisioning a licentious getaway. Maybe the Lackawanna suspects were doing something similar, in reverse. Maybe, unable to resolve their own struggle with what W.E.B. DuBois, speaking of African Americans, called “two-ness,” they were prepared to jettison the “American” part of their hybrid selves, and in the process betray the “Arab” part as well. Or maybe, as an ESL teacher who grew up with them, Hannah Zaid, suggested, they were simply confused. As boys, she said, “they don’t want to be laughed at” for religious observance; “they think, ‘Man, there must be something wrong with me,'” so they reject it. Then “when they start questioning themselves—’Who am I? I want to be a good Muslim. I want to be a good American’—they don’t know how to balance it.” Maybe they were inspired or maybe they were duped, and maybe they had too little critical analysis and appreciation for Muslim variety to help them tell the difference. Whatever their story, in their contradictions and silences, their broken paths amid broken culture, their search for authenticity, malign or misguided, they were All-American Boys, postindustrial style.

Before his arrest, Mohammad Albanna remarked, “People say to us, ‘Why can’t you be an American?’ Well, what is it? If there was any description, it would be to be anyone you want to be under the auspices of the Constitution. Freedom of speech, freedom of movement, freedom of religion—that’s what America is.” As it turns out, at that moment his phones were being tapped and the wheels were turning for his arrest. “We are all responsible for national security,” he had insisted. “If I want to live in a dictatorship, I can live in a lot of places that are warmer than Buffalo, New York.”