Community organizer Eder Sánchez pulls away from a breakfast of liver, rice, and plantains and uncaps his pen. He’s sitting in a roadside cafeteria near the farming pueblo of La Hormiga in the southern Colombian state of Putumayo. Groves of plantain and yucca cut into the tropical forest here alongside fields covered with bushy coca plants. Putumayo is the world’s cocaine frontier, the source of 50 percent of Colombia’s coca crop. Sánchez is here to talk to local farmers about a new, US-funded anti-narcotics offensive targeted primarily at this remote region. He knows that they fear for their future — and he’s concerned about his own.

With the precision of an industrial designer, Sánchez draws a simple map of the area on a napkin: a grid formed by a straight vertical axis (the area’s main road) and a wavy horizontal axis (the Putumayo River). At the intersection is a dot (Puerto Asis, the region’s largest town). The lines roughly demarcate the territories of control in the region. “I can work here,” Sánchez says, poking at the upper left-hand quadrant. “Or here,” he adds, pointing at the lower left. Only a few weeks earlier he was moving fairly freely around the whole napkin. Soon, he knows, the boundaries of power will shift again.

As his economical penwork suggests, Sánchez is a man who seeks clarity in an infinitely complicated situation. He has to. As president of the region’s main farmers’ union, the 33-year-old has spent years traversing Putumayo, educating campesinos about their political rights and helping develop farming cooperatives. In a state where the presence of Colombia’s central government is rarely felt, this has meant moving between zones alternately controlled by leftist guerrillas and right-wing paramilitaries — and remaining as neutral and transparent as possible.

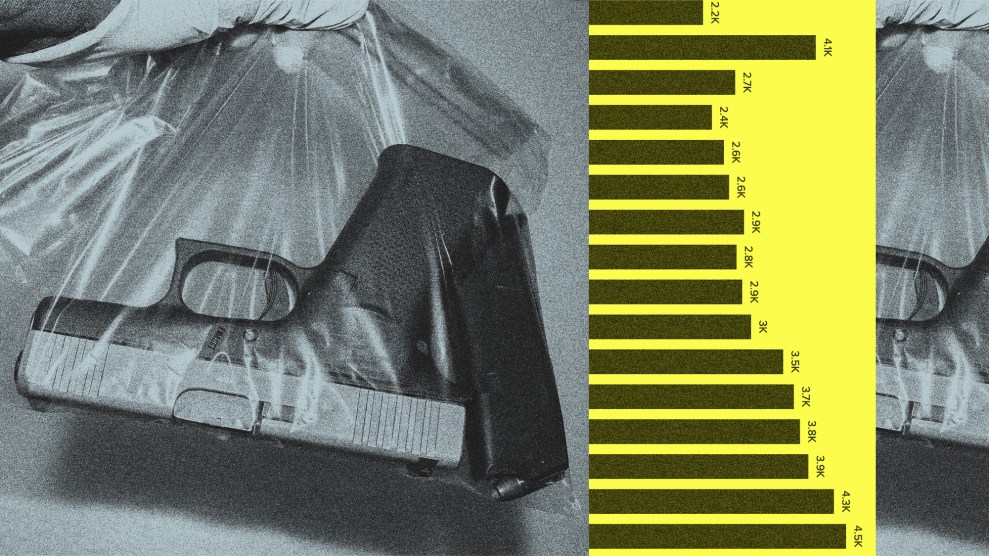

In recent months, the work of Sánchez and other community-based workers in Putumayo has gotten even more difficult. They blame Plan Colombia — President Andrés Pastrana’s massive new effort to simultaneously destroy narcotics trafficking, settle the country’s four-decade-old armed conflict, and rebuild the long-neglected regions where coca is grown. Last summer, Congress approved an initial US contribution to the plan totaling $1.3 billion over two years. Eighty percent of the money is slated to help Colombia’s military and police forces stop drug traffickers throughout the Andes and destroy coca fields and processing plants in the jungle; the rest is earmarked for social programs including human rights monitoring and refugee assistance.

US and Colombian officials insist that the carrot-and-stick approach is essential to Plan Colombia. The Pastrana administration hopes to funnel about $40 million in development funds into Putumayo by February, while at the same time increasing the number of troops and police in the region.

But Sánchez and other grassroots workers maintain that the plan’s military objectives have already compromised the social aspect. The Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia (FARC) guerrillas in particular have taken the plan personally, accusing the US and Colombian governments of launching a counterinsurgency offensive thinly veiled as an anti-narcotics program. “They said they will allow certain [groups] to do their work,” reports Father Luís Alfonso Gómez, a parish priest in Puerto Asis, “as long as they’re not infiltrated by political interests or gringo manipulation.” But, he and other community workers wonder, how will the FARC tell the difference?

Dagoberto Martínez, project director for a Puerto Asis-based nonprofit that provides technical assistance to farmers, says organizers are being greeted with growing suspicion by both sides in the conflict. “It’s more risky than before,” he says. “You can’t be crossing from where the guerrillas are to where the paras are. They’ll kill you because they may think you’re carrying information from one side to the other.”

One of Eder Sánchez’s groups — the Municipal Council of Rural Development, where he served as director until late August — has already been crushed between the warring factions. Last summer a local FARC commander accused the council of abetting the paras (an allegation Sánchez denies) and vowed to destroy the organization. Soon thereafter several campesinos were found murdered outside Puerto Asis. One was a local coordinator for the council. Within days Sánchez resigned his post, hoping that cutting his links with the targeted group would allow him to continue working in Putumayo.

But he fears that he won’t be able to do it much longer. He’s already trying to spend as little time as possible in the Puerto Asis area, even though he has invested more than five years of effort in organizing campesinos there. “The FARC aren’t going to let anyone enter,” he predicts. “It’s a critical situation. I’m very worried.”

Sánchez is not alone in his concern. In August, just before President Clinton’s visit to Colombia, more than 130 national and international community-based organizations announced the formation of a coalition, Paz Colombia, to oppose Pastrana’s strategy. The coordinator of the alliance, Jorge Rojas, says Plan Colombia was poorly conceived and will only aggravate the conflict. “It’s a plan that will polarize Colombian society,” he maintains. “It’s a plan to do away with illicit crops, but it’s going to drive the crops deeper in the jungle and across the borders. We don’t think that it’s going to strengthen peace.”

Jaime Ruíz, Pastrana’s chief political affairs adviser, insists that Plan Colombia’s two-pronged strategy can work. “We believe,” he says, “that if we come in and the community feels the support of the government, feels the state presence, feels it’s there to stay, and if there’s money, reality, commitment, they’re obviously going to start finding that they’re not going to have to choose between either the [paramilitaries] or the FARC.”

From where Sánchez sits, though, such promises come too late. Had the Colombian and US governments been serious about grassroots development, he says, they would have sounded out community leaders well before the plan was presented to Congress a year ago. In fact, the first official delegation from President Pastrana’s Plan Colombia office didn’t show up in Puerto Asis until this summer. In an unfortunate bit of symbolism, the group traveled in a US military transport plane.