Pioneers like Bill Tosheff paved the way for today’s National Basketball Association stars. But while Michael Jordan, Dennis Rodman, Patrick Ewing, and Shaquille O’Neal make tens of millions each year, Tosheff can’t even get a $200 monthly pension.

The 71-year-old former pro basketball player, who played for the Indianapolis Olympians and the Milwaukee Hawks from 1951 to 1955, recalls that back then, the National Basketball League paid players about $4,500 a year, or $27,000 by today’s standards. That’s a far cry from the nearly $2 million that today’s players average.

| Tosheff is co-founder and president of the Pre-1965 NBA Players Association, which represents 65 players excluded from the NBA’s pension plan. In 1965, the league unionized and established a pension fund giving post-1965 players who played a minimum of three years a monthly pension of $285 multiplied by the number of years played. The plan also required pre-1965 players to have racked up five seasons in order to qualify for a $200 per month pension (also multiplied by the number of years played). Tosheff has spent the past nine years lobbying the NBA to close that loophole and include the pre-1965 three- and four-year players. |  |

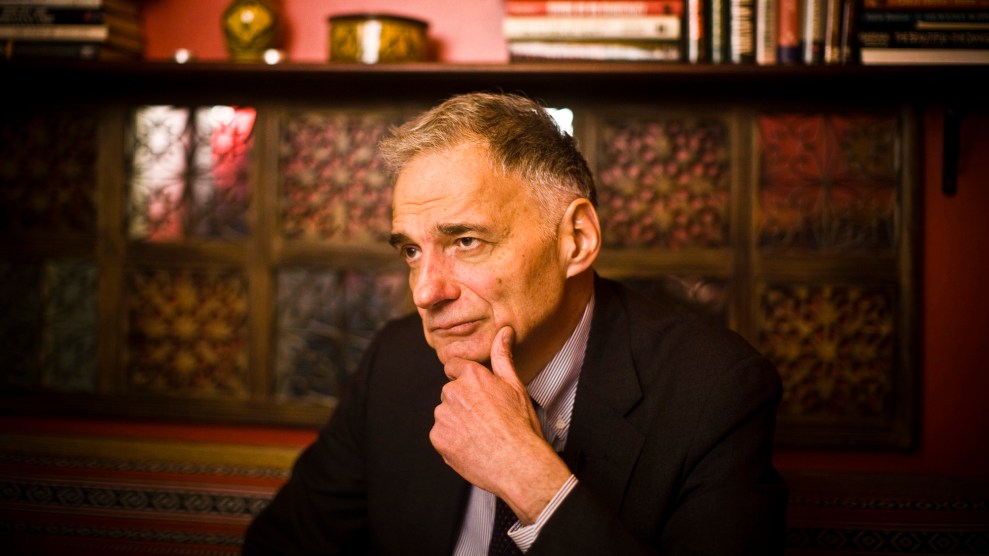

| Pictured in 1952, Tosheff, No.9 with the Indianapolis Olympians, scores two points against Rochester Royal and Hall of Famer Bobby Wanzer. |

The pension fund has close to $103 million, and Tosheff estimates it would cost less than $500,000 a year to include his association’s players—”on a declining basis, because our guys are dying.” (Most of the pre-1965ers are in their 70s.) While Tosheff, who runs a security company for car dealerships, doesn’t need the pension for financial reasons, many of his colleagues do. He says former Boston Celtic John Ezersky, now 75, still works 12-hour shifts as a San Francisco taxi driver. “It’s unconscionable,” Tosheff says. “We did set the table for today’s megabucks business.”

It looks like the pressure is finally paying off: In 1996, in the wake of the NBA’s 50th anniversary, Tosheff attracted the support of Rep. William Lipinski (D-Ill.), who introduced a federal resolution last May to pressure the NBA to include the old-timers. And in November, Billy Hunter, executive director of the NBA Players’ Association, told Mother Jones, “In light of the league’s success over the past 10 years, we’re prepared to help.”

However, Tosheff fears Hunter’s “help” will only mean charity money from the NBA, rather than inclusion in the pension plan. “Too much time has gone by. I’m going to do as much as I can for as long as I’m standing.”