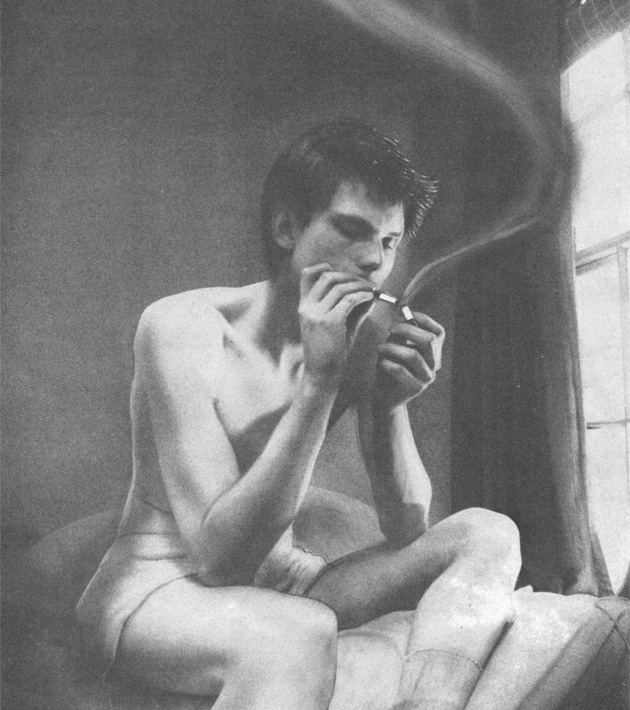

Every morning my husband coughs and gags for about ten minutes. Some days he wakes up choking. On others he is fine until he stands up, then doubles over retching. After 15 or 20 minutes, he can finish a sentence without gasping, walk across the room without bending over in pain, even pick up our two-year-old son without dropping him. Then he gets dressed, has a cup of coffee and lights his first cigarette of the day.

During the next 16 or so hours that he is awake, he will smoke two packs of cigarettes. He will enjoy only a few puffs, and he will give up smoking at least 40 times. Sometimes he gives it up more than once during the course of a single cigarette. During the 16 years–half of his life–that he has smoked, he has stopped occasionally for a few weeks or even months. In such periods, he is able to do little else but search for an occasion–sad, happy or insignificant, any one will do–to justify having a cigarette.

To dismiss this as one man’s neurosis would be a mistake. Dick is only one of a number of people I know whose lives ultimately revolve not around jobs, friends, families, lovers or politics, but around their seemingly incurable attachment to smoking. Probably only eating, sleeping, working or watching television involves more Americans more continuously than does smoking. According to Department of Health, Education, and Welfare figures, about a quarter of the country’s population smokes, and one-sixth, or 37 million people, will die prematurely from it. On a day-to-day basis, that means that, every two minutes, possibly five teenagers will begin smoking–shortening their lives by an average of 5 1/2 minutes with every cigarette–and one of them will die prematurely because of it. As much as we need to know why Johnny can’t read or what makes Sammy run, and even more pressing questions is, why can’t Dick stop smoking?

Dick’s biggest problem is that nicotine–one of the most rapid and fatal of poisons, also used commercially as an insecticide–is physically addictive. It is the soma, not the psyche, that shrieks loudest when smokers try to stop. Recently, Columbia University psychologist Stanley Schachter found that when smokers try to give up the weed, withdrawal from nicotine creates anxiety, which in turn results in acidic urine. This flushes nicotine faster than usual and thus triggers the physical need to light up another cigarette so as to bring the amount of nicotine in the body back up to the usual level of addiction.

More specifically, according to Dr. Hamilton Russell of the Institute of Psychiatry, London, it is the level of nicotine in the brain that is crucial to the highly dependent smoker. Nicotine reaches the brain within a few moments after the first drag, but within 20 to 30 minutes–precisely the lag time between cigarettes for most heavy smokers–the nicotine has dissipated to other organs, and another fix is needed to counter the change in brain wave activity, as registered in an EEG taken at that time.

Our ample supplies of tobacco and social tolerance of both smoking and withdrawal symptoms (“I need a cigarette”) make its addictive property nearly invisible. Nevertheless, this is precisely why tobacco is one of the country’s most profitable and, in turn, most politically powerful industries.

Tobacco’s promoters never stop working. Their activities range from contributions to political campaigns (including the full-tie energies of a Philip Morris executive as the only big-business representative on Jimmy Carter’s 1976 campaign staff) and support for well-placed members of Congress to the advertisements that make most of the nation’s press afraid to print stories like this.

The tobacco industry has also been astoundingly successful. Few Americans remain ignorant for long, for example, of any new cigarette brand that is introduced, yet how many know that:

- According to a 1967 British government survey of teenagers who smoked more than one cigarette, 85 percent become regular users.

- Former drug addicts and alcoholics who have been surveyed consider it’s harder to give up tobacco than heroin or booze.

- The former director of HEW’s National Institute on Drug Abuse, Dr. Robert DuPont, estimates that only 10 to 15 percent of the people alive today who have ever used heroin are still addicted, whereas more than 66 percent of those still living who ever smoked cigarettes are current daily smokers.

- Chemically and pharmacologically, nicotine is related to such central nervous system stimulants as methylphenidate and the amphetamines, which are even more addictive than heroin and other opiates.

- Both drug and alcohol addicts can tolerate drug-free periods, whereas only 2 percent of all cigarette users are intermittent smokers.

Yet despite these classic symtoms of addiction, tobacco is categorized as neither drug nor food (although U.S. taxpayers paid $29.4 million in 1975 to include it in the U.S. Food for Peace export program). The legally required warning label on cigarette packs implies that some sort of inspection has occurred, but tobacco is ignored by the Food and Drug Administration. It is also specifically exempt from regulation by the Consumer Product Safety Commission or the Environmental Protection Agency. And the more than 300 possible cigarette additives, including oxidizers to make them burn better (cigaretters are the leading cause of fatal home fires), preservatives and enhancers designed to compensate for reduced taste in newer low-tar brands, need not even be disclosed, much less examined for carcinogenic or other effects.

What’s more, it is understandably difficult for Dick and this country’s other 53 million smokers to accept that going through the physical and psychological trauma of getting the cigarette monkey off their backs is really worth it, since they’ll still be exposed to countless other pollutants in America’s ongoing game of cancer roulette. Smokers can get almost as much relief without even quitting by just switching to one of the low-tar brands that now account for a quarter of the market and half the advertising dollars. Not only do low-tars let smokers satisfy and exhibit concern for their own health (and that of those around them, who will now be exposed to fewer milligrams of tar every time a cigarette is lit), but these brands also let new smokers become addicted more smoothly, without that initial revulsion that used to turn off at least some potential smokers.

The federal government has followed the same line of thought. Until last year, HEW’s preventative efforts against smoking had been budgeted at under $1 million a year, whereas over $40 million had been spent over the last decade in attempts to develop a “safe” cigarette–the only case in which the government itself had financed a major effort to develop a less harmful consumer product. Indeed, the chimera of a safe smoke is so powerful that, when the National Cancer Institute released a study last August showing that low-tars are “less hazardous,” the media and the tobacco industry ignored the chief researcher’s careful insistence that there is no safe level of smoking, and they virtually heralded low-tars as a solution. Relieved consumers, in turn, pushed up sales of Carlton cigarettes, deemed least hazardous, by 124 percent.

Smokes and Popes

The other major reason that Dick continues to smoke is simply that cigarettes represent not only the good life, but the American way of life. To begin with, every year the United States consumes more cigarettes (4,064 per year for every American) than does any other country in the world. This is only fitting since cigarettes have played a significant–if little appreciated–role in making the United States one of the world’s most heavily industrialized nations.

One of the major problems among workers in the Industrial Age, particularly those in routine lower-level jobs, is tedium. Cigarettes provide the ideal solution: at about ten minutes apiece (plus occasional coffee breaks to give the day a few high points), smokes not only help pace out a day–on the production line, in the typing pool, behind a lunch counter or waiting on a welfare line–but they give you a steady flow of small rewards to keep on trucking. No wonder, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture, cigarettes are the first luxury item poor people buy.

Data from Germany after World War II indicates that even under conditions of extreme deprivation, and in situations where food rations were under 1,000 calories a day, smokers still bartered eats for smokes. (Soviet concentration camp memoirs indicate the same pattern.) Smokers’ need for nicotine was so overwhelming that some also picked up butts off the street, begged tobacco, prostituted themselves or stole other goods that could be traded for cigarettes. In fact, nicotine addiction is so powerful that it may have contributed to the conversion by early North American Indian tribes from hunting and fishing to settled agriculture in order to have a guaranteed supply of tobacco.

Unlike smallpox and venereal disease, smoking was already here when Columbus arrived. A clay pipe found in California has been Carbon-dated to 7000 B.C., and the specific use of tobacco goes back at least to 4th-century Mayan priests in Mexico. As the postmark used by the Tobacco Institute, the major tobacco lobby, proudly proclaims, tobacco was “America’s First Industry.” And it soon became the equivalent to small change as well as the major commodity in trade with Europe.

Opposition to tobacco’s use began early, too. At the beginning of the 17th century, King James I of England named tobacco and papism as evils against which he vowed to do life-long battle. Pope Innocent X agreed with half of King James’ list of evils and excommunicated smokers. Other early tobacco adversaries were Ottoman Emperor Amurat IV who condemned smokers to death, one Czar who resorted to nose-slitting, and the Shah Sifi who had smokers impaled. Most recently, U.S. secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare Joseph Califano, Jr., has labeled smoking to be “slow-motion suicide.” And it has all been to such little avail that tobacco is now grown and smoked worldwide, from Russia to New Zealand, although American tobacco is still considered among the finest.

Cigarettes proved a handy taboo in many ways. With only the defiant flick of a match, anyone, from soldiers on the front to women struggling to liberate themselves from traditional roles, could signal a bold stance to the world. In this century, improvements in tobacco cultivation and processing that made cigarettes easier to inhale, plus public acceptance of women smoking, have caused such an increase in the number of smokers that eyebrows do not even go up when a gentleman offers a lady a Tiparillo. Yet, for many, cigarettes still remain a basic symbol of mystery, daring and sexuality. Cigarettes appeal so strongly to a gut anti-authoritarian instinct that they continue to be smoked in spite of–or, in some cases, because of–steadily mounting evidence of dangers.

Beauty Pageants in Niger

For a while, all this seemed to be coming to an end. During the 1960s, as the civil rights movement, the Vietnam War and the women’s movement were changing the course of history, Americans were also cutting down on smoking after a 1964 Surgeon General’s report linked smoking to disease and death.

Today, there are fewer smokers than in 1964 (except among teenage girls, whose usage of cigarettes has quintupled in that period, possibly because of cigarette ads’ exploitation of women’s liberation), but today’s smokers are smoking more. Simple population growth will increase the number of smokers to 60.2 million by 1980–not a bad record given that a 1975 U.S. Public Health Service poll found that 84 percent of all adult Americans consider cigarette smoking “enough of a health hazard for something to be done about it,” and 82 percent believe it frequently causes disease and death.

Even the cigarette companies are not relying on cigarette sales to stay up forever. Now that 33 states and many more cities and counties have restricted smoking in certain public areas, the industry is busy diversifying into other products, from dog food to beer, as a hedge against the future. Less well-publicized in this country, the cigarette industry is also following what might be called “the infant-formula model”–shifting their sights from the developed world, where consumption may level off, to a vast Third World market eager for symbols of Western affluence and still unencumbered by health and advertising regulations. According to Worldwatch Institute, typical promotional efforts include the Gitane beauty pageant in Niger and Gauloise ads in Africa that stress the cigarette as a mark of high status and virility. Such aggressive marketing is also evident in giant multinationals, like Philip Morris International, whose Marlboro man now sponsors tennis matches and bridge tournaments for the booming Egyptian market. Since 1965, PMI has increased the number of its Asian, African and Latin American affiliates and licensing arrangements from 2 to 13 and from 2 to 9, respectively. As a result, sales of more than 160 brands PMI markets internationally in 170 countries have increased a healthy 18 percent annually over the last decade.

With a 1977 U.S. cigarette advertising outlay of $422 million, or about $2 for every American, what is truly amazing is that only about 25 percent of the population smokes. Of course you don’t win a ball game or a war by just sitting on your butt, so the cigarette companies are continually exploring other promotional ideas. Brown & Williamson, for example, is paying each of 1,500 Volkswagen owners $20 a month to paint their car “Kool” green with a big “9” (to represent that cigarette’s tar content); they’ve also started four other Volkswagen campaigns to promote their low-tar brands. Wary of proposals to the government asking it to prohibit the use of human models in cigarette ads, in 1977 B&W also launched a series of 20 scenic color ads that showed no people, but suggested a “human presence” by including homes in the background.

Other companies have sponsored tennis tournaments (Decade, Virginia Slims), special showings of movie classics (Benson & Hedges), jazz and country music festivals (Kool), ethnic festivals (R.J. Reynolds), golf championships (Kent, Carlton, Doral), and sweepstakes with prizes of mink coats (Max) and a farm in Vermont (Kool). The introduction of commercials into movie theaters also offers new promotion possibilities, which include recycling old television cigarette ads (already done in overseas movie houses).

“Screw the Proletariat”

This display of Madison Avenue ingenuity helps keep tobacco the nation’s fifth-largest cash crop. Last year’s retail sales of tobacco products totaled $17 billion–equal to the entire gross national product of Greece. It’s enough to support 600,000 tobacco farm families and 76,000 workers in the cigarette manufacturing industry, as well as providing revenue to cigarette vendors and government agencies on all levels.

This money also buys a lot of protection. The most obvious is the cigarette lobby in Washington, described by Senator Edward Kennedy as “probably the most effective lobby on Capitol Hill.” At the Tobacco Institute, the industry’s chief lobby, the promotion of tobacco begins as soon as you enter the waiting room, which is dominated by a large wall-sized display case containing row on row of cigarette packs (presumably all 168 brands now on the market) mounted on black velvet. In the inner offices used by the Institute’s staff of 56, bumperstickers and posters on the wall range from “Enjoy Smoking” and “Califano is Dangerous to My Health” to “Screw the Proletariat.” But the Institute’s official strategy depends not so much on smart-ass slogans as it does on a combination of never surrendering the offensive and stonewalling to the death.

Inspired perhaps by the four-volume set of Nixon’s memoirs on his bookshelf, the Institute’s vice president, Bill Dwyer, painted a picture of the tobacco industry as a pitiful helpless giant. “We’re trying to re-establish a controversy in this country,” he told me as he chain-smoked Benson & Hedges. “Most people believe beyond a shadow of a doubt that smoking is dangerous. We’re going against popular prejudices, and that’s very difficult.”

Dwyer calls tobacco “one of life’s natural pleasures,” which, like all other basic pleasures, is subject to continual attack from busybodies and do-gooders. The message he and the people from the Institute deliver to hundreds of civic organizations, schools and local media each year is that there has been no “conclusive” cause and effect established between smoking and health but “merely inferences from statistics,” and that people should listen to both sides and then decide for themselves.

Dwyer does not have a logical argument in favor of tobacco as much as he has a stray collection of quips and quotes. When you question him about statistical links between cigarettes and lung cancer, for example, he immediately becomes a walking compendium of other peoples’ sayings: “Cancer is a biological, not a statistical, problem.” “Smoking is one of the leading causes of statistics.” “Statistics are like a bikini bathing suit: what they reveal is interesting, what they conceal is vital.”

Repeatedly, Dwyer used his audience (me) as the example to back up his point: “If you can decide not to smoke on your own, why not let others do the same?” When asked about how independent a decision about smoking could be, given its addictive properties and the industry’s massive advertising budget, he replied that there is no addictive effect, and that ads influence only the brand choice of those who already smoke, “just as soap ads only talk to consumers about buying Tide instead of Fab, not about whether to wash.”

This skilled persuasion on the public-relations level is backed up by widespread campaign contributions to Congressional candidates. By the end of September of 1978, the Institute’s political-action committee, the Tobacco People’s Public Affairs Committee (TPPAC), had already given money to 157 members of the House (more than one-third of its members) and 15 senators–a gift list that included a number of committees with jurisdiction over smoking programs. By the time of the November 1978 elections, the TPPAC gave away about $61,000 to its friends running for office. Many of these same candidates received support from other tobacco public-affairs committees, such as the newly formed Farmers and Friends PAC of Raleigh, North Carolina. Organized by tobacco growers, this group wants to arrange a voluntary check-off system for the country’s one-half million tobacco farmers, and estimates of its potential receipts range from $200,000 to $3 million.

The lobbyists’ results are impressive. On Capitol Hill, it has meant not only that initiatives such as removing tobacco from the Food for Peace export program have been defeated, but that many issues concerning smoking are raised only minimally if at all. A typical example is an early September hearing held by the House Subcommittee on Tobacco. Sub-committee chairman Representative Walter Jones (D-N.C.) called eight medical and other experts who testified that cigarette smoke is not a health hazard. Nine other members of Congress, all from tobacco states and an unusually high number for a hearing, were on hand, but there was no report of probing questions. Anti-smoking groups had not been informed of the hearing ahead of time. By the hearing’s close, the Tobacco Institute was ready with a three-page press release.

The executive branch has also done its part to counter anti-smoking developments with neutralizing and, occasionally, openly pro-smoking gestures. On the same day that the American Medical Association issued a 14-year study, financed by the nation’s largest tobacco companies, linking cigarette smoking to maladies from indigestion and the common cold to cancer, President Carter made a well-publicized visit to tobacco country in North Carolina. After a few jibes at Califano, Carter said that he saw “no incompatibility” with annual price-support for tobacco farmers and pursuit of a “good health program.” Subsidies to the tobacco industry totaled $35 million in 1977, in addition to a little-known $123 million in federally guaranteed loans to foreign countries for purchases of American tobacco.

Smoking under Attack

The Tobacco Institute’s most active opposition, the “ruthless” anti-smoking forces of which Bill Dwyer complained, have their headquarters about a mile away from the Institutes plush digs. Action on Smoking and Health operates from two cramped, third-floor walk-up rooms on the edge of the George Washington University campus. “Sue the Bastards” says the poster next to the desk of ASH’s founder John Banzhaf. Over a decade ago, Banzhaf forced radio and television stations to provide free time for anti-smoking messages; today, ASH is doing just that. The first organization to file suit to force airlines to provide separate no-smoking sections, and, along with others, has also sued for smoke-free workplaces and public space, ASH is now after the FDA to reclassify nicotine as a drug. (If, by the way, you want to get involved in anti-smoking efforts, ASH is your best bet. It can put you in touch with groups in your community. Contact ASH at 2000 H Street NW, Washington, D.C. 20006; (202) 659-4310.

One of the major problems with the anti-smoking movement, according to Banzhaf, is that although there are more than 1,000 small, local anti-smoking groups, there is no strong, well-financed national nonsmokers’ rights group. The three major organizations that are in a position to exercise leadership, the American Cancer Society, the American Heart Association and the American Lung Association, are “worse than useless,” he charges. “They only use a tiny percentage of the millions they take in for anti-smoking activities, but people think giving them money is the way to fight cigarettes. The result is like having Phyllis Schlafly head of NOW.”

Nevertheless, nonsmokers have been alarmed and moved to action by finding that it is dangerous to be around cigarettes whether you are actually smoking or not. Tearing eyes, painful coughs and estimates that a nonsmoker inhales the equivalent of up to six cigarettes merely by being in the same room with smokers have gradually roused a growing number of nonsmokers to declare that smoking is one American way of death they refuse to accept. Recent research has also found that the annual cost of cigarette-related illness may be as high as $18 billion, more than seven times the tax revenues that have so far rationalized smoking for some government purse-watchers, and a further burden that nonsmokers are increasingly unwilling to assume. As a result, anti-smoking incidents are mounting continually: from the Washington, D.C. woman who poured water over the cigar of a recalcitrant smoker in a restaurant to the New Jersey telephone company worker who successfully sued for a smoke-free workplace.

Over 500 anti-smoking ordinances were introduced around the country in 1976, and there have been no retreats yet in those areas where the restrictions passed. This momentum could grind to a halt, however, after the defeat last November of Califoria’s Proposition 5. This statewide anti-smoking measure was successfully opposed by some $5 million spent to defeat it, financed mainly by five major cigarette companies and consisting largely of skillful television and radio spots linking the attack on smoking to Big Government.

On the national level, HEW Secretary Califano’s anti-smoking offensive, announced last January, includes a proposed ban on cigarette smoking in commercial airplanes, a study on whether or not to raise cigarette taxes (8 cents a pack since 1951) to discourage consumption and a stepped-up program of anti-smoking education. A few weeks later, a widely publicized study issued by the National Commission on Smoking and Public Policy, a group sponsored by the American Cancer Society, criticized the ACS for inaction on smoking and called for stronger measures. The Civil Aeronautics Board followed suit with a decision to ban smoking of cigars and pipes on airplanes.

What is needed now is massive, continual support for smokers who want to stop and encouragement for others not to start. Above all, this means public acknowledgement of the seriousness of cigarette addiction. One of lobbyist Bill Dwyer’s favorite arguments is that “more people are familiar with the official cigarette warning label than they are with the First Amendment,” and therefore smokers are simply exercising their right of choice. But when researchers find that nine out of ten smokers wish to stop, that six out of ten have tried and failed, and that present smoking-cessation techniques, most of which rely on willpower or aversion techniques, have a failure rate of more than 75 percent, smoking looks far less like free will than enslavement.

To ban cigarettes outright would doubtless be as futile as Prohibition, but there is much that could be done. Probably the single most important anti-smoking measure would be to drastically restrict cigarette advertising–either completely or to restrict it to straightforward information like that in financial “tombstone” ads. A total ban on advertising is scarcely a novel idea, for it has already been adopted in Italy, Iceland, Finland, Sweden and Norway.

The evidence that such a ban would lead to an immediate drop in consumption is not yet clear, but one thing it surely would lead to is much more vigorous coverage of smoking’s dangers by newspapers and magazines–which have reaped about $800 million growth of tobacco advertising in the eight years since cigarettes left the airwaves. (In an average year, for instance, TV Guide carries $20 million worth of cigarette advertising; Time, $15 million; and Playboy, $12 million. Parade magazine, the Sunday newspaper supplement, gets a whopping 80 percent of its ad revenue from tobacco.) Without this financial tie, major magazines other than Reader’s Digest, the New Yorker, The Washington Monthly and Good Housekeeping (the only four that do not accept cigarette ads) might open their pages to the in-depth coverage of cigarette hazards they have thus far avoided. A survey a year ago by the Columbia Journalism Review failed to find a single comprehensive article about the dangers of smoking in the previous seven years in any major national magazine accepting cigarette advertising. [Editor’s Note: The Columbia Journalism Review evidently omitted the then-new Mother Jones from its survey. But the magazine’s experience in regard to cigarette advertising has been instructive. Hugh Drummond, M.D., MJ‘s medical columnist in 1977 and early 1978, repeatedly attacked cigarettes in his articles. One column, in December 1977, linked cigarettes with cancer of the lungs, throat, mouth, esophagus, pancreas and bladder, as well as with emphysema and heart disease. Drummond ended his article by noting the irony that “one company–Philip Morris–manufactures both cigarettes and hospital equipment.” Several months later, despite MJ‘s rapidly rising circulation, R.J. Reynolds abruptly cancelled $18,000 worth of cigarette advertising scheduled to run in the magazine. No explanation was given.]

Other critical measures that should be taken include:

- Officially labeling cigarettes “addictive” rather than simply “habit-forming.” This would at least channel anti-smoking attention and funds toward relevant projects such as addiction studies and massive preventative campaigns to discourage nonsmokers from taking even a puff under the illusion that they “can always stop when they want to.”

- Anti-smoking ads.

- Strict enforcement of existing laws against the sale of cigarettes to minors.

- Research into why some people don’t smoke.

- More smoking-cessation counseling and clinics with Medicaid and Blue Cross reimbursement, which will also furnish follow-up studies, so that we can begin to learn what, if anything, will work.

- Making cigarette companies legally liable for the effect of their products, a tactic now being tested by Melvin Belli in a suit he has filed on behalf of the children of a woman who died of lung cancer.

- Development of alternative uses for tobacco. One of the most promising is extraction of fraction-1, a protein that contains more nutritional value than standard animal protein and that could develop into one of the world’s primary nutritional sources.

Such measures would mean increasing the federal anti-smoking budget many times over the $30 million Secretary Califano has requested, but it would be well worth it considering the 322,000 lives lost each year to cigarette-related diseases. And it would certainly be cheaper than the heavy price we all pay by allowing our society to be so shaped by a practice we already know to be deadly to body and spirit alike.

Contributing editor Gwenda Blair is based in New York. After reading a first draft of the beginning of this article several months ago, her husband, writer Dick Goldensohn, stopped smoking and has thus far not resumed. [1979]