As a boy growing up in a small town in southeast Texas in the 1950s, Randy Best couldn’t read. The hours his mother, a high school teacher, spent tutoring him barely made a difference. At the time, he didn’t realize he was dyslexic, and he got through school by dint of hard work. “Either I was going to give up or I was going to find some way to compensate,” Best, now 65, recalls. He eventually discovered that he had a talent for reading the market. By the time he was 27, he’d sold off the class-ring company he’d founded for $12 million, launching a career as one of the Lone Star State’s most prolific and politically connected entrepreneurs.

Best went on to buy and sell off more than 100 profitable ventures—an oil and gas company, a Girl Scout cookie maker, an art magazine, and a military contractor worth $700 million—picking up investments along the way from prominent Texas politicians including former Democratic Gov. John Connally and former Democratic National Committee Chair Robert Strauss. “Those people who have been with him through successful business ventures would put him somewhere between God and the Beatles,” says Patrick Riccards, a former spokesman for senators Robert Byrd and Bill Bradley, who recently worked as Best’s marketer. “His support is truly that cult of personality. Randy Best can inspire people to slay dragons with a butter knife.”

When Best first sat down with George W. Bush in the mid-’90s, the two men quickly hit it off. The first-term Texas governor may have seen in Best what he imagined in himself: a brawler who overcame bad grades and learning difficulties to become a leader, a good ol’ boy who trusted and rewarded his friends, and a self-made evangelist for the free market. And Best had something else that appealed to Bush: an idea for a business venture and social program wrapped into one package, in the form of his fledgling education company, Voyager Expanded Learning.

Best’s idea of approaching education as an investment fit nicely with Bush’s vision of replacing ossified government services with nimble private contractors. With Bush’s patronage, Voyager not only spread through Texas but eventually reaped the benefits of the sweeping, controversial education policy that Bush implemented when he took the White House. Almost overnight, Voyager rose from obscurity to become one of the nation’s most sought-after reading-curriculum companies.

Voyager was not unique in how it rode the president’s coattails to success. The administration’s education policy “enriched a lot of friends and ideologues and entrepreneurs,” says Richard Allington, former president of the International Reading Association and a professor of education at the University of Tennessee. Revolving-door hiring and political connections influenced how the Education Department spent billions of dollars—to the alarm of education experts and, eventually, some former administration officials. P. David Pearson, the dean of the University of California-Berkeley’s Graduate School of Education and a former president of the National Reading Conference, says that President Bush “approaches educational policy the same way he does policy on the war or policy on fema: When there is work to be done, why wouldn’t you share the wealth with your buddies?” The firms that profited from this approach were like “Halliburton for education,” he says. “And Voyager is one example.”

For Best, the Education Department’s adoption of Pentagon-style contracting created another market to tap into. “There’s nothing else as large in all of society,” he says, unselfconsciously exaggerating the billions of tax dollars spent on America’s schoolchildren. “Not the military—nothing—is bigger.”

launched in 1994, Voyager was Best’s first foray into the business of education. After three decades of making money the old-fashioned way, the serial entrepreneur says he caught the philanthropy bug. He launched Voyager as a nonprofit that offered after-school programs as a way to keep latchkey kids engaged in learning. Yet after two years of sluggish growth, he switched to a for-profit model and hired school superintendents from Dallas and a nearby suburb to pitch the program to their former colleagues. Business picked up, and Best became a believer in a market-driven approach to social problems. “If you become a for-profit, then every single person in the organization is incentivized to do what you are trying to do,” he explains. “Their rational self-interest is at stake; it is not just always trying to do something for the greater good.”

Voyager enjoyed an enviably cozy relationship with its customers. After Texas’ education commissioner intervened to help the company dodge child care regulations, competitors complained that it had cashed in on its connections. In 1998, Best and his investors donated more than $45,000 to Bush’s gubernatorial reelection campaign. (Best says they supported Bush “because he was billing himself as the education governor,” not because they expected anything in return.) That August, Bush dropped in on a Houston elementary school and spoke in front of a Voyager banner. Touting the benefits of for-profit after-school programs, he called for $25 million to fund them across the state.

Voyager’s friends in high places were not enough to make it profitable. But by staying close to Bush and his allies, Best learned of new, bigger opportunities. In the mid-’90s, Charles Miller, a Voyager investor and Bush campaign donor, worked with the governor’s office to design a new state reading program, the Texas Reading Initiative. Miller’s team—”this small little mafia,” as he puts it—included Bush’s adviser Margaret Spellings and several others who would go on to occupy key positions in Bush’s Department of Education in Washington. By 1998, Best had reinvented Voyager as a reading program, hiring researchers who’d worked on the Texas Reading Initiative or had ties to its designers.

Best says the idea for the new direction came from his own experience as a dyslexic and his interest in cutting-edge literacy research. “I think Voyager copied from a lot of the things we did with our reading initiative,” Miller says. “Voyager saw that and just got in the draft, so to speak.”

In 2000, Best and Miller signed up as Bush Pioneers, pledging to raise at least $100,000 for the governor’s presidential run. When Bush entered the Oval Office, his education team included several people with connections to Voyager—and some who went on to work for Best. They set out to implement a revolutionary new policy that, despite the talk of smaller government, essentially put Washington in charge of setting state education standards. Miller helped select former Houston schools superintendent Rod Paige, a longtime Voyager booster, as secretary of education. Bush made G. Reid Lyon, a reading researcher who had consulted on the Texas Reading Initiative, his unofficial reading czar. Lyon cowrote the section of No Child Left Behind that created Reading First, a $6 billion program to fund state literacy curricula that drew upon “scientifically based reading research”—exactly what Voyager had been selling back in Texas.

in theory, Reading First was meant to bury the hatchet on the deeply ideological war over reading pedagogy that had waged for several decades. No longer would liberal proponents of “whole language instruction” and conservatives hooked on phonics bicker over the most effective way to get kids to read; scientific research and objective testing would determine which reading curricula really worked and therefore deserved federal money.

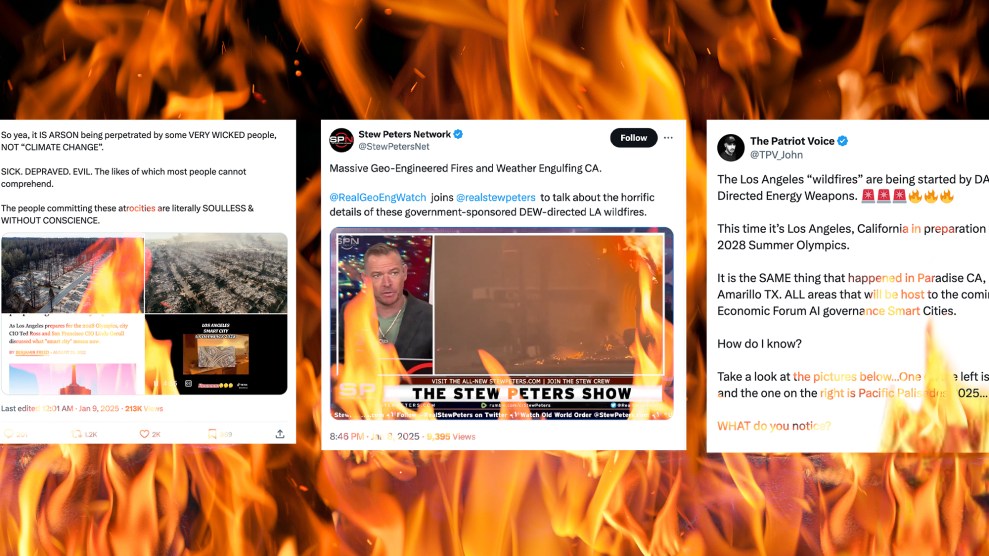

Bush went out of his way to promote Reading First, which the Department of Education described as the academic cornerstone of nclb. (The president was touting the new program at a Florida elementary school, reading a story called “The Pet Goat,” when he was told about the second plane hitting the twin towers on September 11, 2001.) Former education officials say the White House essentially ran the program itself through Spellings, then a domestic policy adviser, and Beth Ann Bryan, a former Miller employee who worked for Paige. After Spellings succeeded Paige as the secretary of education, she compared Reading First to “the cure for cancer.”

Yet bureaucratic obstacles dogged the program from the start. As the Education Department repeatedly denied their funding applications, desperate state officials struggled to divine which kind of reading programs the feds would actually pay for. The states “became copycats,” says Lyon, the former reading czar. “They would hang on to anything” that looked like it might win Reading First grants. And that often meant Voyager.

Best’s education company became, in his words, “a selling juggernaut,” earning roughly $25 million a year from Reading First alone. (See “Best Practices“, for more on Voyager’s success in landing education contracts.) According to Best, Voyager benefited from “really good timing.” He insists that the administration showed no favoritism toward his company. “This administration was so worried about dealing with anybody from Texas and charges of cronyism that we were a pariah,” he says. “They never helped us even slightly in any way that I’m aware of. Ever. The idea that a federal program could help one [company] over another is a myth. They give the money to the state. The state decided who got it.”

Yet it didn’t hurt that Voyager had influential friends. In January 2003, Lyon told the New York Times that New York City risked losing $70 million in Reading First funds because its reading curriculum wasn’t backed by “published research.” A few months later, the city agreed to dump much of its old curriculum for Voyager. Lyon insists he never pitched the company to New York, but adds that a Voyager salesman later told him that someone in the administration “who had used the Voyager thing in Texas and was in a pretty hefty position” had name-dropped the company to top city education officials. Lyon thinks the mention almost certainly helped cinch the deal. Federal law prohibits the Education Department from promoting specific curricula; former Education Secretary Paige says he has no knowledge of the episode.

In 2003, the Education Department created three regional Technical Assistance Centers to help the states navigate Reading First’s bureaucracy. All three center directors had been paid consultants to Voyager, and two were still on its payroll. (One has earned roughly $700,000.) Although Best says the centers did not encourage the states to pick his company, reading experts say the tac directors went beyond established research to push a phonics-heavy approach and other instructional preferences that favored Voyager.

Reading First and Voyager fit together snugly in another important respect. Like other nclb programs, Reading First required standardized testing to evaluate students’ progress. The eight-person federal committee that chose which tests to use included four researchers who had worked for Voyager. One of them, Roland H. Good, had designed a test known as the Dynamic Indicators of Basic Early Literacy Skills, which was similar to a test that Voyager had hired him to build into its reading program. The testing committee approved dibels to assess Reading First students. (Good recused himself from the decision.) Ultimately, 45 states adopted the test. Reading First training handbooks also pitched dibels exclusively, an endorsement that the Education Department’s inspector general later found to likely be a violation of federal rules.

The selection of dibels gave Voyager a leg up on its competitors, since it clearly taught to the test. “If it turns out that your internal assessment tool is the one for which you are going to be held accountable, that’s a pretty good competitive advantage,” says Robert Slavin, the author of a well-regarded nonprofit phonics-based reading curriculum, Success for All. More than 50 studies had shown Success for All’s efficacy, according to Slavin, yet it lost market share under Reading First and laid off 60 percent of its staff. In 2005, Slavin filed a complaint with the Education Department’s inspector general, alleging that Reading First had been hijacked by “a small group of individuals to direct significant federal resources to a small group of companies.” Three inspector general reports subsequently found that favoritism and conflicts of interest may have influenced Reading First’s contracting decisions.

Another reason upstarts such as Voyager beat out more established competitors, explains Pearson, Berkeley’s education dean, is that Reading First did not distinguish between programs that claimed to be research based and those whose performance had been verified by research. Ignoring this important distinction, he says, “makes a mockery of the notion of research-based practice and evidence, because it basically says research-based practice is whatever we want to push.”

When Reading First’s accountability moment came, it wasn’t pretty. The Education Department’s first review of the program, conducted in 2006, found that it was being “implemented as intended.” However, that review was partly conducted by the contractor that had helped create Reading First. Yet a review this past April found no evidence that Reading First students read better than those not in the program. Lyon and Spellings dispute those findings, pointing to improved reading scores released in June. That month, House and Senate appropriations subcommittees voted to cut all funding for Reading First in 2009, citing its poor performance.

For all its talk of research and results, Voyager’s report card has also been less than impressive. Last year, the first major federal comparison of reading curricula found that Voyager’s reading comprehension scores were lower than any of its competitors’. Success for All earned a positive score and Reading Recovery, another package that lost out under Reading First, placed third out of 19 programs. The report concluded that Voyager actually had “potentially negative effects” on its students.

but by the time Voyager and Reading First received their crummy grades, Randy Best had moved on. As with most of his earlier businesses, he’d gotten out when the going was good. In early 2005, as Voyager’s curriculum was being taught in more than 1,000 school districts in all 50 states, Best sold the company to ProQuest, a database company, for $360 million.

“We never thought we’d make a dollar, and then the company sold for a lot of money,” Best recalls, sitting in his opulent office in a Dallas skyscraper. He says that Voyager served its original goal, which was to teach kids how to read. Recalling the “endless stacks of mail” he received from happy parents, teachers, and principals, he says, “It was a wonderful experience. We have served over 5 million kids. That’s what it’s all about.” A quotation from Ronald Reagan hangs on the wall nearby: “There is no limit to what a man can do or where he can go, if he doesn’t mind who gets the credit.”

Best “didn’t care who got the credit, but he did care who got the profit,” quips Jay Spuck, a retired dean of instruction with the Houston Independent School District. “He laughed all the way to the bank.”

Shrugging off such criticism, Best has focused on ever-more-ambitious for-profit education ventures. In 2005, he started the American College of Education, an online business that offered master’s degrees to teachers. His expansion plans for ace were foiled by college accreditation boards—”cartels,” as Best describes them. But he rebounded, unveiling a similar master’s program last year in an unusual partnership with his alma mater, Lamar University in Beaumont, Texas. He’s also launched Whitney International University, a $100 million scheme to create the largest university system in the world, with campuses throughout Latin America and the Middle East and eventually India and China. “We’re able to reduce administrative costs, instructional costs, and facility costs dramatically,” Best says. “And we pass on all that savings to the student.”

In 2005, G. Reid Lyon left his job as the federal reading czar to work for Best. He spent two years heading an assessment team at ace, but recently quit in frustration because, according to former colleagues, he came to believe that Best didn’t want to do internal research that might expose problems with the college. “There was little appreciation for data or accountability,” says one former ace employee. “That just wasn’t in the business plan.”

Lyon will not comment about his work for Best, but he now has second thoughts about Reading First’s marriage of public education with good-ol’-boy business culture. “Many programs, including Voyager, were probably adopted on the basis of relationships, rather than effectiveness data,” he told Mother Jones. “I thought all this money would be great; it would get into schools. But money makes barracudas out of people. It’s an amazing thing.”