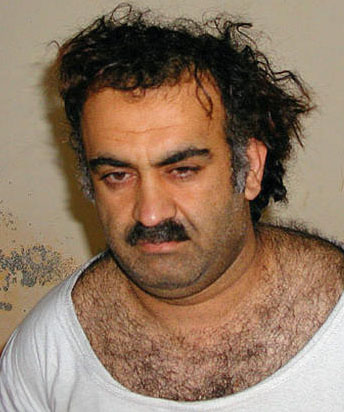

Yeah, this guy. (US Government Photo)Khalid Shaikh Mohammed will get a trial:

Yeah, this guy. (US Government Photo)Khalid Shaikh Mohammed will get a trial:

Khalid Shaikh Mohammed, the self-described mastermind of the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, and four other men accused in the plot will be prosecuted in federal court in New York City, a federal law enforcement official said early on Friday.

It’s not an exaggeration to say that this will be the trial of the decade. The trial carries enormous political risks for the Obama administration, and it draws attention to all of the hardest and most interesting questions about America’s response to September 11th. It’s pretty clear—as clear as it can be without a trial—that KSM’s a bad guy. He’s not some Afghani opium farmer or taxi driver. He almost certainly is who we think he is, and he almost certainly knew things that could be useful in the fight against Al Qaeda. So the Bush administration decided to torture him. If we’re going to decide as a country whether or not we’re going to torture people and what we’re going to do with people after we torture them, we should focus on the case of KSM. He’s the hard case. Now the country will have to deal seriously with that hard case. That’s a good thing.

Unfortunately, the Obama administration couldn’t quite muster up the courage to try all the Guantanamo detainees in federal court:

[T]he administration will prosecute another set of high-profile detainees — Abd al-Rahim al-Nashiri, who is accused of planning the 2000 bombing of the U.S.S. Cole in Yemen, and four other detainees — at the military prison at Guantanamo Bay, Cuba before a military commission, the official said.

The American Civil Liberties Union, which praised the decision to try KSM, slammed the decision to use the military commissions. “It’s disappointing that the administration has chosen to prosecute some Guantánamo detainees in the unsalvageable military commissions system,” Anthony Romero, the ACLU’s executive director, said in a statement Friday morning. “Time and again the federal courts have proven themselves capable of handling terrorism cases while protecting both American values and sensitive national security information. Justice can only be served in our tried and true courts.” Glenn Greenwald has a great wrap-up of what needs to be said about today’s moves by the Justice deparment:

[T]he more consequential impact of Obama’s decision is likely to be overlooked: we’re now formally creating a multi-tiered justice system for accused Muslim terrorists where they only get the level of due process consistent with the State’s certainty that it will win. Mohammed gets a real trial because he confessed and we’re thus certain we can win in court; since we’re less certain about al-Nashiri, he’ll be denied a trial and will only get a military commission; others will be denied any process entirely and imprisoned indefinitely. The outcome is pre-determined and the process then shaped to assure it ahead of time.

But by creating a multi-tiered system, the Obama administration is undermining its own position. The government’s previous position may have been represensible, but it appeared to be consistent—terrorism detainees don’t get real trials. Now that the administration has shown that it is willing to try some of the “most dangerous” detainees in federal court, it will be hard pressed to articulate a constitutional rationale for why some detainees get trials and others don’t. You can probably expect a constitutional challenge to this multi-tiered system.

Update: Well, that last sentence isn’t exactly right. The ACLU’s Ben Wizner pointed out to me that prosecutors often get a choice of forum in our justice system—between federal courts or state courts, for example. The separate systems aren’t inherently unconstitutional, and the military commissions are being challenged on their own merits, anyway. But it’s clear that transferring the biggest cases to the federal court system makes it harder for the administration to claim that its choices of prosecutorial venue are based on anything other than its chances of winning. “Ultimately we’ll need to look at who goes into which forum and look at if there’s any rationale besides the strength of the case,” Wizner says.

The administration is already essentially admitting that it is making its decisions based on its assessment of the chances of conviction. “I would not have authorized prosecution if I was not confident our outcome would be a successful one,” Attorney General Eric Holder told reporters Friday morning. That’s a pretty stunning statement.