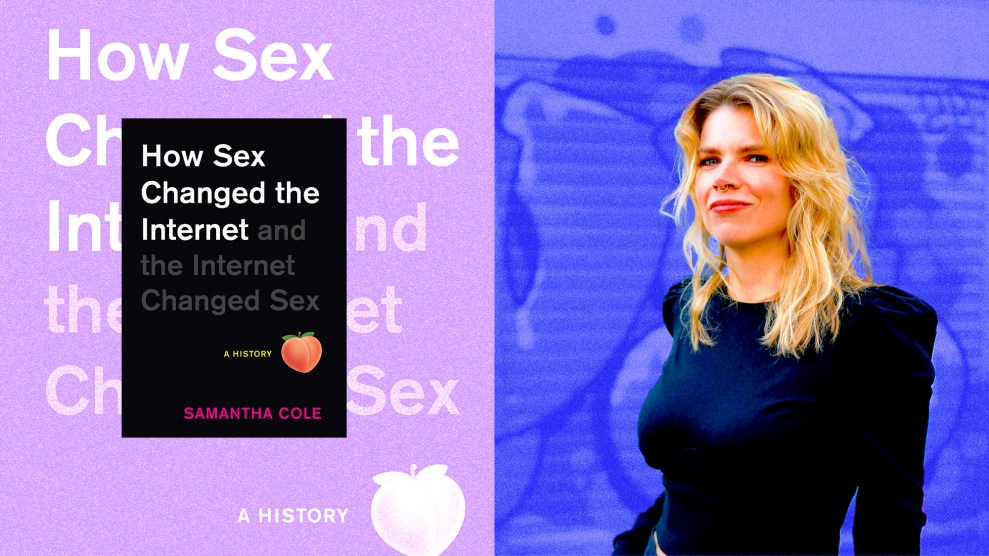

Mother Jones illustration; Sharon Attia

The first video ever posted on YouTube was of co-founder Jawed Karim making a dick joke. Jennifer Lopez’s famous green Versace dress was essentially the reason for the creation of Google Images. A picture from Playboy was used for decades to test image processing tasks on computers. Sex has essentially created the digital, online world as we know it today, in ways that you probably didn’t know about. This is the thesis of Motherboard Senior Editor Samantha Cole’s debut book, How Sex Changed the Internet and the Internet Changed Sex.

It’s a history that continues to be written, but Cole’s book is a uniquely comprehensive take. The book touches on core human issues and feelings like consent and power, examining how the internet has played a role in them when it comes to sex—such as with deepfakes, which are used to superimpose one person’s head on another person’s body. At times the sheer frankness is overwhelming and difficult to read, especially when it comes to descriptions of how the internet is used in regards to sexual violence. But one senses that it’s incredibly important to know what’s hidden (or not) behind our screens—depths which many of us have not even begun to comb through. For example, the woman whose Playboy image was used, Lena Sjööblom, didn’t even know that was the case until many years later, when she was invited to appear at the 50th Annual Conference of the Society for Imaging Science and Technology in 1997.

I spoke to Cole, whose book is out on November 15th, about covering the topic of sex and the internet, technological advances, censorship, and upcoming internet trends.

How did you get involved covering issues of sex and gender?

I had a pretty sheltered upbringing. It’s surprising to me and probably people who know me that I cover this stuff for a living now. I started in journalism right out of college, and then was kind of doing a lot of feature writing and profiles and things like that, and talking to people about their very human experiences. And then from there, I moved to New York and started writing about science and space. I really did a gearshift in the past six years. I’ve only been focused on things like platforms and moderation and how the internet works and how people use the internet specifically, because so much of our lives are now on the internet. There’s no real life. What’s happened on the internet is really our lives. The coverage that I’ve been doing around sex and sex work and gender has been, really, the most interesting part of my career. And that’s kind of why I’ve stuck with it.

In the book you talk about how a lot of these technological advances, like message boards, were further advanced by a want for sex and love. What do you think that says about humanity and our connection styles?

I think it says something very vulnerable and sweet about the way that we just want to be seen and be known [and] the way that we want to define whatever that is. On these old text based systems and chat rooms, you could describe the way that you were and it could be completely different than what you are in real life. And you could kind of play around with that online and see, you know, who it attracts, how it makes you feel to embody that other person that you want to be online. I guess we do that to a degree, just in our interactions in real life, too. No one’s really like, fully, fully yourself, when you’re talking to coworkers or in a professional setting or something like that; you’re projecting what you want people to see. And I think people did that, to an extreme extent, online when it was first forming. And people do it now on Twitter; nobody’s really who they really, really are on Twitter.

I think it says that people just are wanting to be heard and to be understood on a level that’s very basic, that is enabled by the internet in a way that we’re still grappling with, and still dealing with how to understand each other through this technology.

There’s a scene in your book that deals with a sexual assault in a chatroom. Essentially, players in the virtual room could type out what they were doing, but a hacker took over others’ accounts and made them type out that they were doing graphic things related to sexual violence. As I read that part, I realized how horrifying it really was for the people who were online in that chatroom. Can you talk more on your thoughts about consent in these chat rooms?

It definitely spoke to how enmeshed people felt with their lives in the chat room. Like, that was very much an extension of their very real lives: That was their friend group, their social group. I’m not saying that’s the only thing they did. They have lives outside of that, but in that space, they were in it in a very real way. It’s kind of hard to draw a line about what is and isn’t assault in a chat room like that. And I think we’re still having that conversation in a lot of ways. You’re allowed to talk now about what is sexual harassment in VR, like in a VR headset, and the metaverse. You can take the headset off, but were you harassed in that situation? So I don’t know, I don’t think there’s an easy answer as to what always is and isn’t considered “bad enough” to be assault in a virtual space like that. But I think you have to listen to people’s stories and hear what they were experiencing and what they were feeling and kind of go from there.

What are some trends, good or bad, you see arising in the coming five years or so when it comes to sex on the internet?

The pessimistic view is things will just continue to get more and more sterilized and censored. It’s hard not to see it that way. Because the reality right now is that things aren’t getting more free and welcoming to sex, they’re getting more hostile. And more and more platforms are saying, “We don’t welcome sex of any kind.” So, I try to resist that point of view because I don’t think it’s entirely helpful. And I also think that we have a say in how it goes; we’re building this thing, to some degree, as we go. People can change the course of things if they feel passionately about it, so that’s what gives me hope. Things can change for the better. We just have to be really loud about it.

We’ve seen censorship of, as you mentioned in the book, for a long time. You trace it back to erotic novels of the 1700s. What do you see as the through line between those erotic novels and current censorship?

You have to really go back to the Puritans to understand the ways that sex and anything remotely sexual is censored online. Because it is a standard that was started, like you said, with these old texts; banned books have been a thing since books were books that weren’t the Bible. It boils down to conservative Christianity and that entire movement really becoming the dominant force in saying what is and isn’t moral and morality, then dictating behavior and what you can and can’t do in your own personal life. I think all of that feeds into what we see happening now, which is this big push from conservative, right wing Christian theocracy types who want porn and sex and nudity and everything off of every platform on the internet. They’re drawing on a really long history of censoring that sort of thing from all realms of life. And now the main realm of life that we have is the internet.

You mentioned SESTA and FOSTA (Stop Enabling Sex Traffickers Act and Allow States and Victims to Fight Online Sex Trafficking Act) being so detrimental for sex workers. But you also mentioned the 2019 Congressional House Intelligence Committee’s hearing on deep fakes, which have been used to make fake porn of people. Do you see any role for the government or law enforcement to play in online issues relating to sex?

FOSTA/SESTA was framed as this sex trafficking prevention measure. It’s good to prevent sex trafficking, no one in the sex industry is like, “Yes, more trafficking,” and a lot of people who are in the industry are victims or survivors of trafficking. And so they’re all intertwined. But those bills didn’t talk to those people, they didn’t consider the perspectives of people working in the industry right now. Those people definitely made their opinions known. They went to Capitol Hill, they lobbied against it; they still lobby against it, they still fight against it. I think that was the main issue there. So, if there was going to be any government help, oversight, anything in regards to these industries, it would need to include those people, not just the people who want to see it abolished. If you’re trying to prevent trafficking, you should start with housing and income and lots of other very basic things that are much harder to solve than wiping sex workers off the internet.

As you did just now, and as you do in the book, you seem to take a stance that sort of seems like an activist, would you agree with that categorization?

This is the question I think a lot of journalists ask themselves is, where’s the line between activism and journalism? I consider a lot of activism to also be journalism. There’s no unbiased journalism. You see these things happening and you’re not necessarily taking sides so to speak, but you know, you’re seeing what’s going on in these communities and you want to tell the truth about it. And the truth may not be what one side likes. So I don’t consider myself an activist full time, though I think there is a lot of activism to be done in journalism. We all make choices in which way we’re going to frame a story, but you have to decide which way is really the most true to the situation. And with things like FOSTA/SESTA, it was very clear that the reality of the situation was people were being hurt. And that’s not what legislators were telling. That’s not the story they were telling; they were telling the opposite.