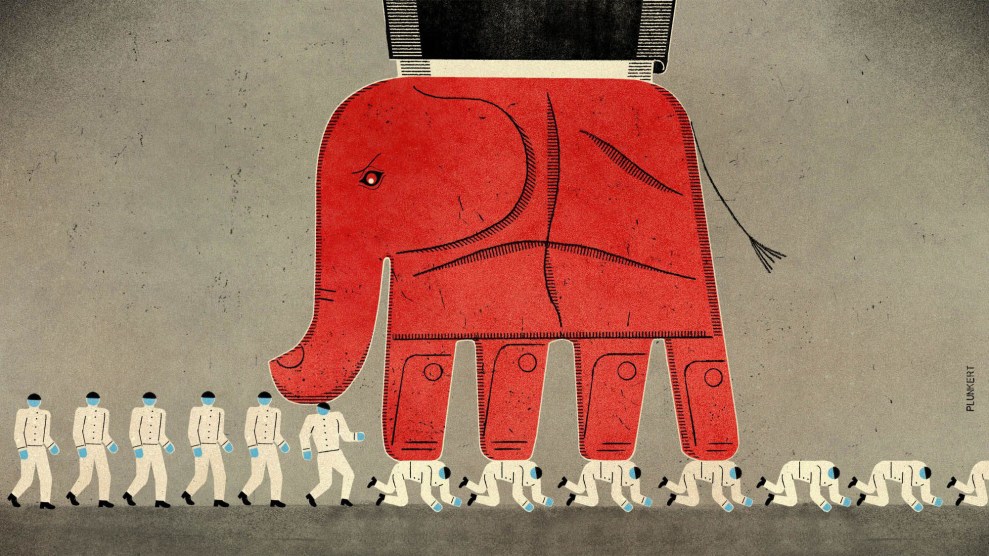

Mother Jones illustration; Getty

It was Inauguration Day, and Joe Biden and Kamala Harris were being sworn in. It seemed like the nation had, just barely, survived one crisis after another—the Trump presidency, a horrific pandemic, and a coup attempt that had been thwarted only two weeks earlier.

But at Mother Jones, I had a different sort of crisis to contend with. As production director, I coordinate the manufacturing of our print magazine. We were finishing up the March+April 2021 issue, which was scheduled to go on press in a week. Trump was on the cover again. This time, he was cradling Josh Hawley and Ted Cruz, two wannabe authoritarians wiggling like infants impatient to be released from their restraints.

There was an urgent email from my supplier: Our order of 70,000 pounds of paper would be delayed. The rolls were on a train car that had been loaded at a paper mill in the Pacific Northwest and was bound for the printer in Wisconsin. The shipment, he regretted to inform me, wouldn’t arrive until Monday, a mere 48 hours before it was needed on press.

That unsettling news ignited a flurry of calls and status updates. On Monday I learned that inclement weather over the weekend had caused the train to miss two switches somewhere near St. Paul. By the time it finally made it to the Milwaukee rail yard, it was stuck in a massive traffic jam of cargo waiting to be transferred to trucks, which were in short supply across the country due to 80,000 unfilled trucker positions. Even if our paper somehow reached the plant by press time, it would arrive completely frozen from its winter trek across the northern states. The massive rolls of paper—50 inches in diameter, weighing 2,500 to 3,800 pounds each—would need at least two days to thaw before they could be hoisted onto a high-speed web printing press.

We print Mother Jones at Quad, a firm that employs 15,000 people in its manufacturing facilities in the Milwaukee area and additional plants around the world. The four Wisconsin facilities mail so many magazines and catalogs that they are considered the largest post office by volume in the state. Ultimately, it was Quad’s employees who rallied to locate enough paper to bail us out, and our coverage of Trumpism and the aftermath of January 6 made it to subscribers and newsstands on time.

But that wouldn’t be the last time the global supply chain crisis would threaten to derail Mother Jones.

Making a magazine has always been a complex story of sourcing, sustainability, and logistics. Paper manufacturing and transport are essential to the $760 billion global print market. The whole process—harvesting timber and hauling it to pulp mills, getting the ingredients to the paper machines, shipping paper to pressrooms, and delivering the finished product to readers—depends on an interconnected network that is vulnerable to global and local events.

I’ve purchased paper through all kinds of market conditions over the years: energy shortages, sudden plant closures, tariffs, and transportation disruptions. I’ve always been able to procure it, but in the last 18 months, everyone I speak with starts each conversation, “I’ve never seen anything like this.”

The Pacific Northwest mill we bought paper from was hit with a ransomware attack that hobbled it for months. We switched to a mill in Wisconsin, reasoning that purchasing from a company closer to our printer would be an additional supply chain safeguard. But with the trucker shortage, which is likely to double within the next 10 years, it turns out that even a few hundred miles can be an obstacle.

On the first day of this year, 2,000 workers at a major paper company in Finland went on strike, shuttering mills and stymieing production of everything from packaged food to medical products. The paper shortages across Europe during the long-running labor dispute also meant there was no possible relief for the shortages in North America. After four months, the workers finally got the bargaining agreements they’d held out for, but concerns remain for the supply chain.

Mother Jones is a bimonthly periodical that uses two kinds of paper: an 80-pound grade 3 for the cover pages and a 40-pound grade 5 for the body pages. Demand for publication paper—called “graphic paper”—has steadily declined as digital information sources have proliferated, so there are fewer mills making it than there were a decade ago.

The pandemic squeezed supplies of graphic paper even further—9 million tons have disappeared from the global market since 2019 due to mill closures or machine conversions to packaging grades. Publishers of periodicals buy graphic paper regularly and must weather the ups and downs of availability, pricing, and transport. Demand from other paper buyers, however, decreased significantly during the 2020 lockdowns as businesses curtailed normal operations. Mills turned their attention to packaging, tissue, and labels, converting even more paper machines away from making graphic paper. Then, by the second quarter of 2021, demand for graphic paper rose dramatically, exceeding pre-pandemic levels. Supply could no longer keep up.

All this led to the resurgence of a phrase that had faded since the 1990s: strict allocations. When the demand for paper exceeds manufacturing capacity, mills impose a system that allocates all portions of their output to specific merchants—even their best customers can get only a fraction of what they want.

The precarious situation had worsened as we approached peak season in the fall of 2021, when demand for print is at its greatest. Our paper supplier warned me that our order, this time for the January+February 2022 issue, could not be delivered until after we were supposed to go on press. Strict allocations were in effect.

Without that shipment, our inventory at the printer was short by about 10,000 pounds. If I couldn’t close the gap, we might not be able to print enough copies to serve all our readers. But we’ve made a promise to those readers, and Mother Jones subscribers are the primary support for our independent journalism. Quad’s press time was tightly booked, and it had its own supply chain and pandemic staffing challenges. I didn’t want to lose our slot; the press date is a hard deadline, and missing subscriber and newsstand delivery schedules has real financial consequences. I had missed only one scheduled press date in my whole career. That happened in January 1988 when a roof collapsed at my printer in Waseca, Minnesota. Tragically, two people died on the pressroom floor, and several others were injured.

This time, it was my paper supplier who saved the day; she managed to find a few rolls and, better still, get them delivered in time to close the inventory gap. That paper would cost nearly double the price we were paying at the time, but I jumped at the opportunity.

The supply-demand imbalance for publication paper is likely to continue through at least 2023. Our prices have increased 38 percent in just the last six months, and each of our deliveries has become a nail-biter. The paper shipments for our May+June and July+August 2022 issues were delayed beyond our original press dates. No longer a once-in-a-career occurrence, these late deliveries forced us to push back our production schedule. To make matters worse, the Wisconsin mill we’ve been purchasing from recently announced that at the end of the year, it’s converting its graphic paper machine to instead make packaging.

Currently, magazine publishers, and the readers they serve, must rely on last-minute heroics in an increasingly chaotic market. This is not sustainable. We need to shore up manufacturing systems to meet demand, find more ways to train and support workers, and stabilize our supply chains. As I consider the tremendous forces at work and all that is required from so many to produce a print magazine, what lingers in my mind is how tenuous it all is, how interlocking our nations, our industries, and our democratic imperatives are. Our readers will have to wait to have the next issue of Mother Jones in their hands. But I know they appreciate what a miracle it is that the magazine, and our journalism, exists at all.