Mother Jones illustration; Getty

I thought this assignment would be easy: Call a few scholars and settle the question of how to pronounce “omicron” in English, once and for all.

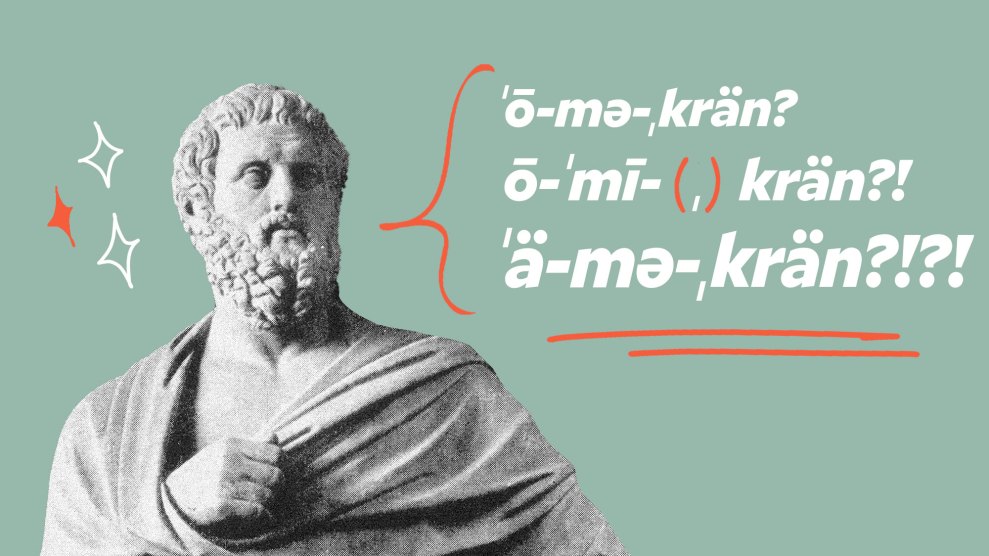

Since the new coronavirus strain was discovered last week in South Africa, I’ve heard newsreaders and leaders alike use at least half a dozen variations, with accent-inflected mutations—a mix of oh’s and ah’s, me’s and my’s. President Joe Biden added to the confusion Monday morning when he said “omni-chron,” throwing in an extra consonant that lent the air of a secret island lair where an evil genius hatches a dastardly plan.

But my search for a correct pronunciation was soon snagged in the crosscurrents of academic traditions and linguistic pickles dating back millennia. Eager to issue their takes, top classicists inundated my inbox.

Let’s begin: Google. Here, as in the Merriam-Webster dictionary, there are standard English variations, separated by the Atlantic Ocean. You can play the audio and explore the nuance. Across the pond, the British pronunciation sounds like the “o” in “toe” or “row, row, row your boat”—long and round. The American employs a flatter, shorter “o,” like in “pot” or “hot.”

Go ahead, take a moment to say them both out loud for yourself.

Case closed? Nope. The more I clicked around, the British/American divide didn’t hold. In this clip, the country’s top infectious disease expert and notable American, Dr. Anthony Fauci, says it the so-called American way. A patriot! His interviewer, CNN anchor and notable American Jake Tapper? The British. And on and on, across the airways: a true transatlantic stew.

Time to hit the phones. My first call was to David Sider, an American scholar with a terrific Bronx accent, in whom I found an equally frustrated ally. “You’ve called the right person!” he exclaimed. “I was driving in a car the other day, listening to the radio, and hit two different people on two different episodes say ‘ah-ma-CRON. And that’s wrong.”

“Kind of like the French president?” I asked. “Ah, Macron!”

“Yes, yes, exactly,” he said. “I’ve been bothered.”

Sider, a New York University professor who teaches Hellenistic poetry and philosophy, took me back to around the 5th century B.C. The Ancient Greeks sometimes referred to a singular letter “o” , he explained, citing evidence in Plato and others. But as various ancient dialects and lettering systems evolved and resolved, experts say, two forms emerged, a short “o” sound and a longer “o” sound, a development traced into the medieval Greek period, several hundred years later. That’s why there are two “o” letters in the Greek alphabet: omicron and omega. Micron, as in “microscope,” means small; mega, like “megalomanic,” means large. Literally, omicron means “small” or short “o” and omega means “big” or long “o.”

Despite this, Sider was emphatic: It’s pronounced “OH-micron,” he said, like row, or toe, with the emphasis on the first syllable. This is how Sider himself has said it for “decades and decades,” as well as how he says his academic colleagues use it. In English, he explained in another email, it wouldn’t make sense for people to shorten the o in the phrase “short o”—the literal meaning of the word “omicron.”

The plot thickened when I emailed Miriam Leonard, who, despite being a professor of Greek literature at University College London, across the Atlantic, favors the shorter, so-called American “o.” “Issues of ancient Greek pronunciation are never an exact science,” she said. (For reference, check out how the word is pronounced in modern Greek, as it is spoken today.)

Especially when you take into account accents and personal history. Natasha Bershadsky, an expert in Ancient Greek myths and rituals, at Harvard, said her “instinct is to go with long o, ‘toemicron’ not ‘hotmicron.'” But she joked, “Asking a native Russian speaker about the English vowels would not get you printable results.” She added helpfully, “When or if we get to ‘chi’ and ‘phi,’ I could give my commentary about the ancient Greek way to pronounce it, with aspiration, which is highly compatible with coughing.” We’ll check back in with Natasha if, lord help us all, we get that far down the list.

Hardy Hansen, a Brooklyn College classics professor at City University of New York, prefers the shorter “o.” “If I’m just referring to the letter ‘omicron’ in English, I give it the pot/hot o-sound,” he said, before highlighting what the experts ended up circling in some way: “The original pronunciation of the vowel in Ancient Greek is another, lengthy discussion.” In any case, Hansen says, conventional pronunciations of Ancient Greek often don’t preserve the distinction accurately.

I am obliged, now, in the pursuit of journalistic fullness, to get into those distinctions.

Among the seven scholars I consulted was a range of opinions about how the ancient Greeks themselves pronounced vowels, and what bearing, if any, that should have on modern English. Ralph Rosen, chair of graduate studies in the University of Pennsylvania classics department, for example, told me “omicron” in ancient Greek was pronounced using a short sound like pot or hot. “That doesn’t mean it’s ‘wrong’ to pronounce it like ‘row,’ but if you want some way of deciding your preference, I would begin with the original pronunciation,” he said. For the record, he says, he favors the short “o.”

Another person on Team Short “O”: Joseph Howley, the director of graduate studies and an associate professor in the Columbia University classics department. “I find this useful as a mnemonic of sorts,” he explained in an email. “Pronouncing the first syllable in ‘omicron’ like an omicron [rather than an omega] is helpful to me and my students, or so I imagine.”

Not so fast, says Elizabeth Scharffenberger, a lecturer also at Columbia University, specializing in Athenian drama in the classical period and its reception in later eras. “The difference in pronunciation between the two vowel sounds is, theoretically at least, strictly one of quantity,” she said. “That is, the length of time for which one holds the sound—and not one of quality. So that would be the difference between saying ‘toe’ really quickly and holding on to that vowel sound for an extra beat.”

Scharffenberger favors the longer “o” version in English in the classroom, though inevitably mixes it up in the wider world. “Habit, after all, is a powerful thing!” she said. “And language is, if anything, dynamic and fluid; it never stays put!”

Why, I wondered, was there such a mixture of takes among classicists? Howley pins it on the nature of academics itself. “American academia in my field is heavily cross-pollinated with UK academia,” he said. “But both are ‘correct’ as far as I am concerned.” Short-o enthusiast Hansen at CUNY agrees: “I often hear oh-micron, and I think that’s equally acceptable.”

So here we are. As with so much in life, a choice, and one that might not matter that much as long as you’re consistent or can get away with a British accent, or a lovely Bronx accent, or do it with style. And while we await the official NPR and Associated Press takes, the typical arbiters of newsreader styles, there’ll be take-havers. There always are. “Doubtless someone else will tell you only one pronunciation is correct,” Howley warns. “This is because my people (philologists) are by nature pedants, and it sometimes goes to our heads.”

P.S. I say, in my Australian accent, “OH-micron.” I’m going to stick with that.