A Trump supporter wears a T-shirt referencing Captain America during a protest in Miami on November 5, 2020.Chandan Khanna/AFP/Getty

So much of the drama in The Falcon and the Winter Soldier, a Marvel show that wrapped up its first season last week, revolves around a circular piece of metal painted red, white, and blue. What does it mean to hold this shield, to adopt the mantle of Captain America? Is it possible to defend a country without sharing its values?

If you watched last week’s finale, you know the show’s answer to those questions. Sam Wilson, given the shield by his mentor, Steve Rogers, finally becomes Marvel’s new Captain America. The decision was fraught with symbolic consequence, as Isaiah Bradley, an elderly Black soldier who was imprisoned and isolated after receiving superpowers in a US military experiment, told Sam. “They will never let a Black man be Captain America,” he said. “And even if they did, no self-respecting Black man would ever want to be.”

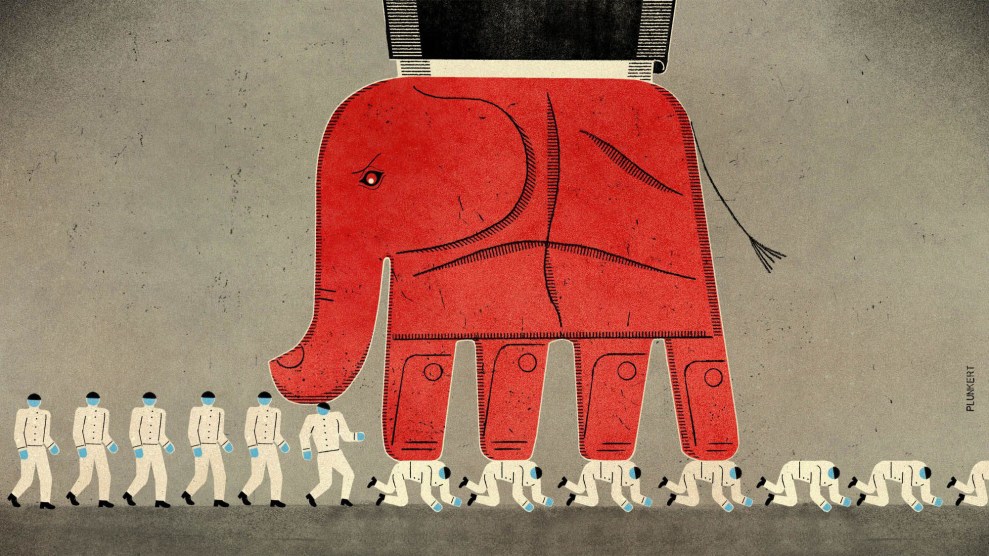

That statement is not only a response to Bradley’s own horrific mistreatment, but a reflection on how Captain America is itself a troublesome concept in a world where the US government often acts in opposition to the ideals that such a figure claims to represent. The contradiction—a noble hero fighting to defend an ignoble institution—has been at the core of the character’s comics appearances for decades. More recently, that conflict has transcended the page and entered our political arena as Cap, like other fictional icons, has been appropriated by far-right extremists in a way that has surprised—and, frankly, horrified—the fans who know him best. A literal Nazi puncher somehow ended up being used as a symbol for an insurrectionist mob that stormed the US Capitol trying to disrupt the transition of power earlier this year. The wildly popular Marvel Cinematic Universe has made Steve Rogers a household name, but by broadcasting a vision of Cap to the masses, the movies have also obscured the character’s complicated history.

From the moment Steve Rogers, the most popular and enduring incarnation of Captain America, appeared on the cover of a comic book in 1941 punching Hitler across the jaw, he became part of the relentless, US propaganda machine—inside both the fictional Marvel Universe and our own world. Rogers, the creation of two Jewish comics legends, was an anti-fascist symbol of American might, willing to fight Hitler nine months before the United States even entered World War II. His early appearances valorized the US war effort and depicted Japanese soldiers as demented caricatures, complete with fangs and yellow skin.

Even the physical comics served as propaganda. Early issues included advertisements for war stamps and bonds that were meant to draw young readers into supporting the war. “Wake up Americans! Drive the Axis to decay by buying war stamps every day!” read one promotion.

Decades after his creation, a new group of comics creators influenced by the Vietnam War era’s distrust in government developed Rogers into an independent-minded skeptic, whose caustic assessments of US power often belied his star-spangled origin. In the 1970s, Rogers briefly resigned as Captain America after uncovering a Watergate-like conspiracy and in the classic 1986 storyline “Born Again,” when a US general questions Rogers’ allegiance to the US government, he brusquely replies, “I’m loyal to nothing, General—except the Dream.”

I couldn’t help but think about that line as images from the January 6 insurrection at the US Capitol flooded social media in the days following the event. There were ludicrous sights like the self-proclaimed “QAnon Shaman” decked out in horns and a furry hat and other, more troubling signs of the protesters’ links to far-right militias and extremist groups. But what caught my attention (and the rest of the Nerd Internet) were the protesters wearing Captain America–inspired gear. Here was a superhero who was conceived as anti-fascist propaganda being appropriated by the supporters of a racist bully who, unable to accept his decisive election loss, had encouraged his supports to storm the seat of government and stage a putsch.

It was easy to laugh at the irony of these insurrectionists using the symbols of an anti-fascist to prop up their failed messiah. Like most comics fans, I nodded in appreciation when Neal Kirby, the son of Captain America co-creator Jack Kirby, released a statement expressing horror at the appropriation of his father’s character: “Captain America is the absolute antithesis of Donald Trump.” (As a corporate entity Marvel tried to stay out of the fray, though its chairman, Ike Perlmutter, was a major Trump donor.)

I had far more trouble trying to explain away the sight of another well-known Marvel Comics logo at the insurrection: the Punisher’s skull. Fans of his comics appearances or Netflix show know the character’s basic setup: Frank Castle is a military veteran whose family is brutally killed by the mob. He becomes a one-man-killing-machine with none of the moral qualms that limit characters like Spider-Man or Batman, who also turned to vigilantism after a personal tragedy. Instead of whiz-bang gadgets or supernatural powers, Punisher comics reveled in his knowledge of military-grade weaponry. There is no Joker in the Punisher’s world—he would have been killed without a second thought.

The Punisher is, at best, a complex antihero, but the nuance of his story seems lost to the legions of police officers, militia members, and soldiers who have adopted his logo. (Oh, and Sean Hannity too!) Chris Kyle of American Sniper fame, raved about the Punisher in his autobiography, writing, “He righted wrongs. He killed bad guys. He made wrongdoers fear him.” Kyle’s unit spray-painted the Punisher’s skull on their vehicles and body armor, using it as a veiled threat. “We wanted people to know, We’re here and we want to fuck with you.”

The shield and the skull signify different things, but each serve as reminders of the power of superhero comics to transcend their origin to suit a new audience. Steve Rogers can be the flag-toting cheerleader for the Allies in World War II and the disillusioned outlaw, loyal to no government but the one that ought to exist, the union that can only become “more perfect.” That is the Steve Rogers I root for as a fan, but it’s not the character that the insurrectionists see. To them, his costume is not so different from the Punisher’s skull. Both are pieces of US propaganda that can be appropriated to fit the nativist, ahistorical mindset that reigned supreme under Trump.

The last time it felt like Captain America had taken over my social media timeline was May 2016. That month, writer Nick Spencer and artist Jesús Saiz launched a new Steve Rogers comic with an eye-popping twist: Cap is—and has always been—evil. In fact, he was an agent of Hydra, the expressly Nazi-like organization that has long been one of his recurring foes.

Plenty of major superheroes—from Spider-Man to Green Lantern—have broken bad for a brief spell, only for their actions to be explained away later. (Safe bet: they were possessed!) It would be no different with Rogers, who returned a year later as a hero after the crossover Secret Empire, in which “Evil Cap” was revealed to be a product of the Cosmic Cube (or something like that…comics are weird). But before Marvel could even release the story, it had to weather an intense pushback from fans and critics who were apoplectic about the heel turn given the Jewish roots of the hero’s creators. Even Chris Evans, who plays the character on screen, was shocked. “Cap is essentially a figure of strength for the Jewish people, comic book fans especially, and now we find out he’s been a Nazi this entire time?” Vox‘s Alex Abad-Santos asked.

The story could not have arrived at a more fraught time. Donald Trump was on his way to being elected president, an event white supremacists celebrated with Nazi salutes. Suddenly Captain America imagery began appearing at far-right rallies. In August 2017, white supremacists with Captain America-inspired helmets showed up at the deadly Charlottesville rally. Later that month, Anthony Oliveira, an author and eventual Marvel writer, tweeted a picture of a white supremacist wearing an officially-licensed Hydra shirt.

just noticed the neo-nazis doing security for white nationalist Christopher Cantwell are in HYDRA t-shirts. pic.twitter.com/zE7bYBTKT6

— Anthony Oliveira (@meakoopa) August 17, 2017

These incidents, coming after Marvel encouraged comic store employees to wear Hydra shirts to promote Secret Empire, fueled more scrutiny of the story’s uncomfortable parallel to the rising fascist movement in the United States. It also put a spotlight on the merchandising boom that coincided with Marvel films becoming the biggest summer blockbusters, which has turned once-niche characters into cultural icons while diluting their original purpose.

The Punisher is the perfect case study for this problem. Originally created by writer Gerry Conway as the villain in a 1970s Spider-Man story, he transitioned into a bloody antihero whose violent means did not always register to fans as necessarily bad. A key turning point came when his series transitioned to Marvel’s “MAX” label in 2004, which allowed for grittier stories that were untethered from the main Marvel Universe. “There is no place for a Punisher in society,” J.D. Williams, a Punisher fan and Marine Corps veteran told Vulture in 2017, ahead of the premiere of the Netflix show. “That said, some of the qualities that the Punisher has are very admirable. Strength, tenacity, perseverance, decisiveness.” (In a 2005 issue, it was estimated that the Punisher killed “as many as” 2,000 people.)

Whatever their reasons for identifying with him, the Punisher’s skull symbol became ubiquitous among US troops and even Iraqi security forces during the War on Terror. The irony was not lost on his original creator, Conway, a conscientious objector to the Vietnam War who in 2019 said that cops and soldiers flaunting the Punisher’s symbol is no different than “putting a Confederate flag on a government building.”

Marvel at first did not see the Punisher’s uniformed fanbase as a problem, even nodding to it in the comics. Kevin Maurer, a journalist who writes frequently about the military, contributed to a Punisher story where the character interacts with a group of soldiers who take his symbol as their emblem when they deploy to Afghanistan. “I was trying to explain why every special operations guy I know basically has a Punisher patch of some sort, and why every conex and trunk had a Punisher skull painted on it somewhere,” Maurer told Task & Purpose.

With Evil Cap, Marvel couldn’t afford to take the same attitude of looking the other way; the online rancor got too overheated given Cap’s symbolic importance and wider fanbase. In May 2017 the publisher assured fans that, yes, Steve Rogers would be a hero again sometime soon. “What you will see at the end of this journey is that his heart and soul—his core values, not his muscle or his shield—are what save the day against Hydra and will further prove that our heroes will always stand against oppression and show that good will always triumph over evil,” a Marvel statement read.

At its essence, the multi-year Evil Cap controversy was not much different from the crisis that had troubled Steve Rogers on the page. He has always worried about whether the more treacherous actors within the US government would use his image to further their own nefarious aims. After Secret Empire concluded with Heroic Cap restored to prominence, the journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates began an extraordinary arc with the character where Rogers grappled with the meta idea of seeing your face be co-opted by evil people. The storyline began, ironically enough, with a riot at the National Mall in Washington.

“A group of military men, brainwashed fundamentalists, faces literally draped in the American flag, staged an assault on the capital. They were angry at the government for not remembering them and their sacrifices to an illegitimate, repressive regime that bore the nation’s name,” writer Jude Jones of ComicsXF recalled. This “illegitimate” nation was led by Cap’s evil doppelgänger, but it just as easily could have been overseen by Trump or one of his various white supremacist fanboys—people who always believe themselves to be victims when they act like the villains.

“The idea is that Cap almost stands apart in many ways from the organs of the country,” Coates told the New York Times. “Really, he is supposed to be about something bigger, and that is the ideal of what America is supposed to be. So what he is doing when he talks about these stories is he’s trying to figure out…how can he operate in a country that falls so far?”

Isaiah Bradley, the Black hero persecuted by the US military, was asking a version of the same question when he told Sam Wilson that “no self-respecting Black man would ever want to be” Captain America. In a heartwarming scene in The Falcon and the Winter Soldier finale, Isaiah comes around to Sam’s choice to be Cap. I cheered at the sight of Sam finally donning the mantle he clearly deserved, but couldn’t help wondering if Isaiah was right to poke at that central contradiction. Captain America was not created as a symbol of fascism and his later appearances show a remarkable evolution into an anti-establishment skeptic. But the more his logo and costume get used by the worst kind of people in our society, the harder it becomes to separate out these comic creators’ intentions from how the symbols have been deployed in the real world.

Marvel hasn’t published a regular, ongoing Punisher series since fall 2019, when the last issue of writer Matthew Rosenberg’s series was published. A miniseries featuring the Punisher and his archenemy Barracuda was scheduled for April 2020, but never released. “One of the things about Marvel characters—some of them—is they are so much a product of the era in which they were created,” longtime Marvel editor Tom Brevoort said in an interview last week on Word Balloon, a popular industry podcast. “And over time, times change.”

The last series that made it to print featured a scene that, if anything, seemed to be in dialogue with the kind of people who so blatantly ignore the character’s criminal past. A group of dirty cops show the Punisher his symbol on their car, gleefully telling him, “Some of us believe in what you do.”

The Punisher rejects their alliance and says, “You boys need a role model? His name is Captain America, and he’d be happy to have you.”

That scene, which was first flagged for me in an article by AIPT (a comics site that I also write for), reads at first as a dividing line between the immoral Punisher and moral Cap. Even the fictional Punisher seemed to have grown a conscience about how his image had been appropriated. But after the insurrection and far too many white supremacist rallies with Cap’s logo paraded around, it almost seems like a cruel joke. The same people appropriating our villains are now appropriating our heroes.