Mother Jones illustration; Brands of the World

Earlier this month while washing dishes, my dad jokingly asked my mom, “Can you talk right now or are you doing ‘hot girl shit?'”

My sister and I looked at each other in shock. My dad, a bit clumsily, was remixing a popular TikTok. This genre of TikTok usually depicts someone pretending to cut a phone call short in order to do “hot girl shit.” This can mean anything from applying glamorous, Euphoria-style make up to playing Minecraft. Either way, Megan Thee Stallion’s “Girls in the Hood” blasts in the background.

@wehatelissa

It was hilarious and weird to hear these words come out of my father’s mouth because it signaled to me just how much TikTok had influenced the way we communicate. Admittedly, we had spent the past day repeating the phrase. Even so, the standard of what’s meme-able, and how the app has shifted perceptions of reality during the pandemic, has been bracing.

As of April, the Chinese-owned app had over 315 million downloads in the first quarter of 2020 according to market analytics firm, Sensor Tower. When TikTok launched in 2018, not long after absorbing its predecessor Musical.ly, it filled a crucial gap in the world of short form video. This was only two years after Twitter bought and killed Vine in 2016 (RIP to a real one).

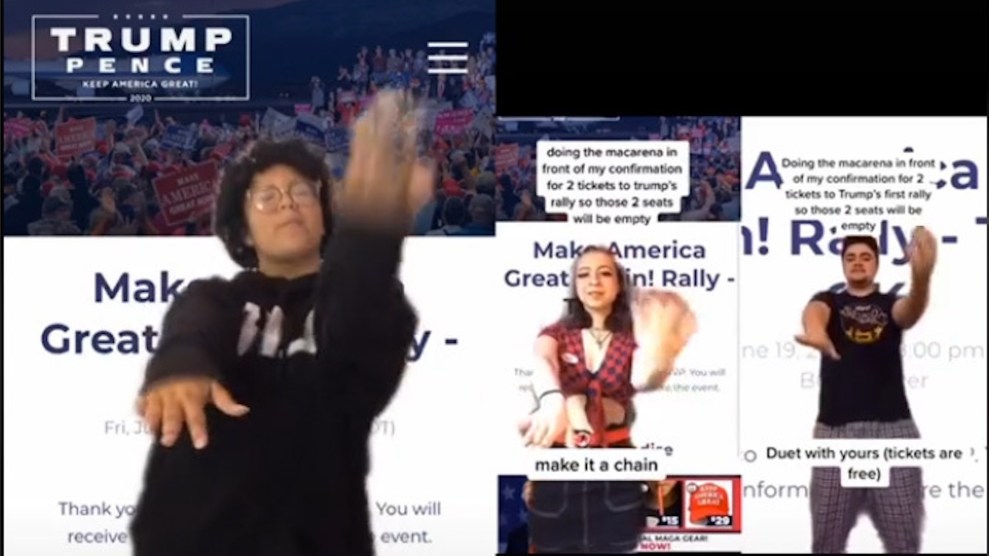

TikTok snuck into every facet of life, seeping onto other social media platforms like Instagram and Twitter, birthing new celebrities, music, and lingo. Briefly, it became the subject of debate around national security. This year, TikTok became our way of curating and articulating our pandemic lives in short phrases and gestures—of making each moment of life memeable—even when we didn’t hit record.

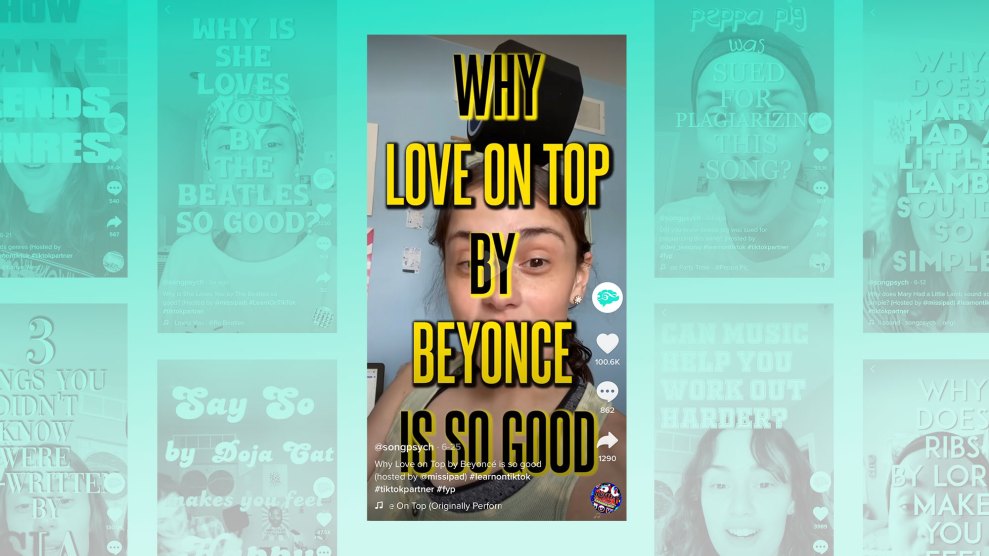

This has allowed TikTok to offer an unending window into niche pockets of the world beyond our own as we quarantine. The app transports you from planttok to skatertok to lesbian TikTok, and to even more unexpected windows like cartel TikTok and prison TikTok. Everyone from Jason Derulo to the Washington Post to Kellyanne Conway’s daughter, Claudia is on the app. TikTok helped pass the time: it forged online communities, cultivated the next generation of cinematographers, and provided an outlet for many Zoomers to process the turbulence of 2020.

But what’s monstrous about TikTok—a massive and unwieldy piece of artificial intelligence—is how much it allows users to dominate those spaces once they’ve found them. Many of TikTok’s most popular sounds and dance trends are created by Black people. And then appropriated widely. TikTok owes its growth, in part, to digital blackface, and how profits and virality garnered from the app more often fall into the hands of wealthy white teens. Digital blackface—wherein non-Black users use Black slang, affect, and body language to essentially put on a virtual minstrel show—is not unique to TikTok. Its roots run deep into every facet of the internet from memes, to GIFs, to the catchphrases and sounds used on TikTok many of which feature images or audio by Black people. It goes back to Elvis Presley.

On TikTok, non-Black creators mimic Blackness by lipsyncing audio or writing comments ripped from Black reality television, Black YouTubers, and ordinary Black people in the media. Minstrelsy is rewarded by ascending these videos to viral heights while the voices of Black creators and the complexity of Black experiences—beyond racist troupes—are eclipsed.

Black creators like @demimykal have tried to draw attention to how younger TikTokers have “literally colonized and white washed almost every Black cultural trend” online. Yet there are no signs that online minstrelsy is slowing down. Besides, what would American internet culture even look like without it?

Just four days before George Floyd was killed by police officers in Minneapolis, Black creators on TikTok staged a “black out” to raise awareness about how Black people were treated on the app and urged users to change their profile pictures to a black fist and follow other Black TikTokers. Two weeks later, the company released a statement apologizing for the unfair treatment of Black creators and announced plans to build a creator diversity collective.

Today, TikTok continues to express its commitment to combating racist algorithms and elevating Black voices. But digital blackface is a widespread epidemic.

On the best days, TikTok is a beautiful crisis of infinite worlds—too many rabbit holes to fall down and a welcome respite from these uncertain times. On its worst, it sheds light on America’s obsession with clout and money, and appropriating not only Blackness, but many communities of color, without giving credit where credit is due.

I am uncertain about the future of TikTok, how the app will evolve or continue to befuddle governments around the world, how it will dictate our vernaculars, our dance moves and the music that plays on the radio. I just hope that in the year to come we can appreciate viral videos for their singularity, their glimpse into the random messiness of life captured online not at the expense of people of color.