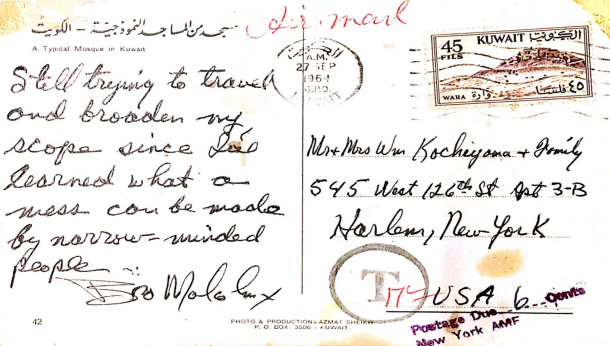

Yuri Kochiyama, the civil rights activist who was incarcerated for two years during World War II along with 120,000 other Japanese Americans, shared a birthday with her friend Malcolm X: May 19. Both were born in the 1920s. And both were at the Audubon Ballroom, in New York, on February 21, 1965, when assassins fatally fired shotguns and pistols at Malcolm as he stepped to the podium. “I just went straight to Malcolm, and I put his head on my lap,” she said of that night. “He just lay there. He had difficulty breathing, and he didn’t utter a word.” Five months earlier, Malcolm had sent Kochiyama and her husband a postcard, from Kuwait, which read:

Still trying to travel and broaden my scope since I’ve learned what a mess can be made by narrow-minded people. Bro Malcolm X

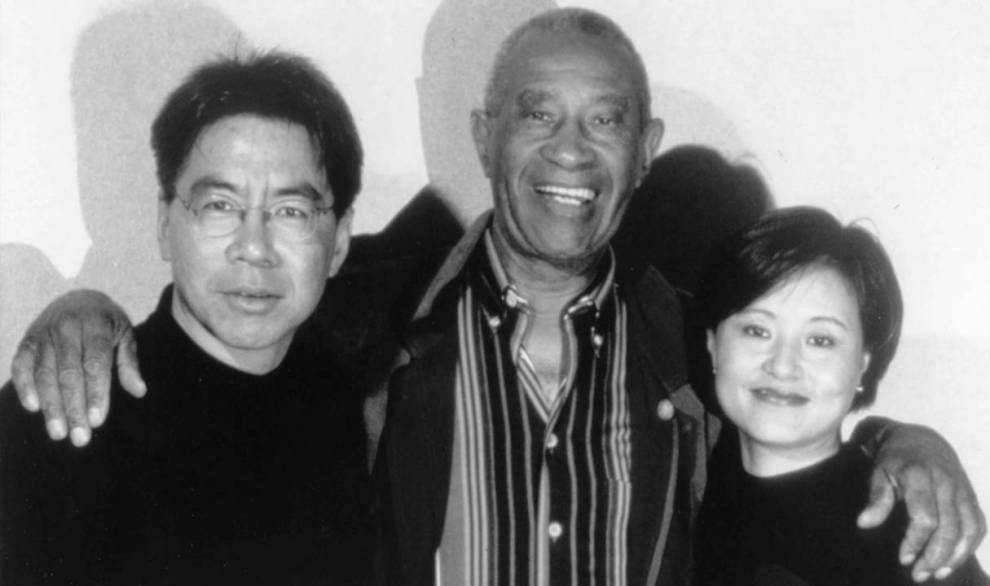

Paired by history and separated by violence, they also inspired the jazz ballad “Yuri Kochiyama, Malcolm X!,” the first track on the album The Pledge of Black-Asian Allegiance, by the pianist Jon Jang. Jang’s song is less lamentation than affirmation of the activists’ solidarity. At 66, Jang himself is a foundational figure in freedom movements. He co-founded Asian Improv Records, composed the first symphony about Chinese immigrant laborers, taught the first courses on Asian American musicians at UC Berkeley and UC Irvine, and was the first American jazz pianist to perform in South Africa after the election to end apartheid. He launched the celebrated careers of Vijay Iyer and Miya Masaoka. Jang’s livestream last week, “So Many Tears,” laid bare the lacerations, the strength, and the visions of Americans who search for change.

“I am an American musician. I perform American music—so that’s Black music,” he said, echoing Amiri Baraka, his mentor, who in 1965 founded the Black Arts Movement after Malcolm’s assassination. Baraka and Jang performed together at the first Malcolm X Jazz Festival, and Baraka’s book Blues People: Negro Music in White America (that he published as LeRoi Jones) gave language and literary fire to Jang’s political engagement. “The Ballad or the Bullet?” is Jang’s tribute to Malcolm’s “The Ballot or the Bullet” speech, and “Hands Up! Don’t Shoot!” is Jang’s blues for Michael Brown. “Jasmine Among the Magnolias” is his memorial to Sen. Blanche Kelso Bruce, the lone Black senator who, in the 1800s, defended Asian immigration, and to Frederick Douglass, who spoke out against the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. Jang’s Pledge ends with a tribute to his mother, who died in 2017. Jang’s father was killed in a plane collision over the Grand Canyon in 1956.

The courage to feel, let alone express, what trauma does, and what can be done with it, is what gives Jang’s music a deeper resonance than just its historical allusions. His music asks again and again, What does solidarity sound like, and where can it lead us? I spoke with Jang, who lives in San Francisco, this week. Our conversation has been edited and condensed.

You renamed your livestream from “Racism in Chinese America” to “So Many Tears.” What motivated the change?

I didn’t feel it’s appropriate that the theme was around Chinese America because of what’s going on with the national protests right now. “Racism in Chinese America” was in response to Trump renaming the coronavirus the “Chinese Virus,” but “So Many Tears” focuses on the legal lynching of Black Americans and the historical racist myth that Chinese Americans are carriers of the deadliest diseases. The title refers to Tupac Shakur’s 1995 composition as well as my commissioned song “Can’t Stop Cryin’ for America! (Black Lives Matter).”

Your music memorializes essential history. How do you go about pairing people and places with musical forms?

I knew that Aaron Copland wrote “Lincoln Portrait” to memorialize Abraham Lincoln, so I took a similar approach. I chose Chinese folk melodies, and it had to be Cantonese. “More Motherless Children” is about the murder of nine Black churchgoers in Charleston. A number of the victims were mothers or grandmothers, and I thought about their children. A white supremacist coming into their space and just killing them. So I used dissonance. The music shows the chaos.

Your song has historical echoes of John Coltrane’s 1963 “Alabama.” He patterned his saxophone lines after the cadences of Martin Luther King Jr.’s eulogy for the four Black girls killed in the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing. How do you see freedom movements today?

I feel celebration when I see statues like the slave-trader Edward Colston’s taken down, rolled, and thrown into the lake. I think of how, in Black spirituals, water symbolizes freedom, and I think about Virginia, where protesters tore down the Columbus statue and threw it in the lake.

The largest museum of Asian arts in America announced the removal of its founder’s statue. Avery Brundage was a Nazi sympathizer and notoriously racist as president of the International Olympic Committee. It took the independent efforts of artist Chiraag Bhakta and community insistence to push the museum to action. How do you see this moment?

It’s uplifting. I think about the history of lynching, which wasn’t just a hateful mob—it was a social activity where white men brought wives and children to a public event, much like a picnic setting. They would take a Black person and lie that he’d killed or raped a white woman or stole something. They’d parade him around, torture him, castrate him, cut his fingers off, burn him. They’d save body parts as souvenirs. I feel history. I feel the present. I feel the joy and celebration of the removal of statues, but I feel sadness. Statue removal is one way to honor Black people’s ancestors and, to a lesser extent, my ancestors. Frederick Douglass, for example, fought for Chinese immigrants’ rights to become US citizens.

Frederick Douglass also inspired your version of “Jasmine Among the Magnolias.”

That’s the first Chinese folk song brought over to the United States, in 1800, originally “Beautiful Jasmine Flowers (Mo Li Hua).” It was the motif in Puccini’s last opera, Turandot, and there’s a pro-democracy group called Jasmine, whose members protested the Chinese government and played “Jasmine” on their cellphones.

The White House invited you to play the same piano in 2013 that had accompanied Marian Anderson, the Black singer who’d been barred in 1939 on the basis of race from performing indoors, so she sang outdoors instead to 75,000 people. What was playing her piano like?

It was an incredible honor. The Daughters of the American Revolution banned her from performing in Constitution Hall, which is where I performed. Eleanor Roosevelt had helped Marian perform outside instead. Marian performed “My Country, ‘Tis of Thee”:

Bettmann/Getty

Hulton Archive/Getty

Keystone-France/Gamma-Keystone via Getty

Tami A. Heilemann

You also recorded with Maxine Hong Kingston, who said your music brings “Chinese identity with American identity into a Chinese American identity.” How do you hear that?

It’s like what Jeff Chang wrote in my liner notes, that my music is a hybrid of Chinese music and Black music. My “Butterfly Lovers Song” comes out of the history of Jesse Jackson appearing as the first presidential candidate ever to speak in San Francisco’s Chinatown. Mabel Teng, who introduced Jackson at the Democratic National Convention in 1984, wanted me to perform a traditional song for the Chinese immigrant audience.

You mention Jeff Chang’s writing, and he traces your relationship with Amiri Baraka, who praised you. Baraka said you’re an “important voice reflecting any actual ‘America.’” How did Baraka influence you?

I’m honored by that. Amiri believed in the Black cultural revolution and he was father of the Black Arts Movement and a leader of the League of Revolutionary Struggle, which I was a member of. I got to perform with Amiri a number of times.

How do you see Ralph Ellison’s famous view of Baraka? Ellison strongly disagreed with Blues People, saying Baraka was “overinvesting in totalizing ideology,” as Robert O’Meally put it.

When Amiri became father of the Black Arts Movement, it was after the assassination of Malcolm X, so we have to understand Amiri in the context, but with all the shortcomings Ellison might have seen, Blues People was the book to read. Amiri was a star. There were thousands of people coming to see him perform. He attained a kind of celebrity status. In the early years, I idolized him.

Another idolized leader in the music is Marcus Shelby, the great bassist on your livestream. Marcus is a legend. He also recorded Soul of the Movement: Meditations on Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

The first concert Marcus did was at San Francisco’s Chinese Historical Society of America. Marcus and I had a Black-Asian solidarity concert, and I went into the Black community and Marcus went into the Chinatown community. But I’m careful to reject the notion that there’s an Asian American music aesthetic or Asian American jazz. That’s why Deborah Wong’s book Speak It Louder is subtitled Asian Americans Making Music, not Asian American Music.

Deborah’s book is brilliant, and it celebrates you throughout. She describes “an implicit historical critique contained in the act” of making jazz. Is there also a future-looking critique?

Yes. The role of the artist is to interpret the past, define the present, and imagine the future. The project now is to reimagine America.

An excerpt of Jang’s “So Many Tears” livestream:

Andy Nozaka

Andy Nozaka