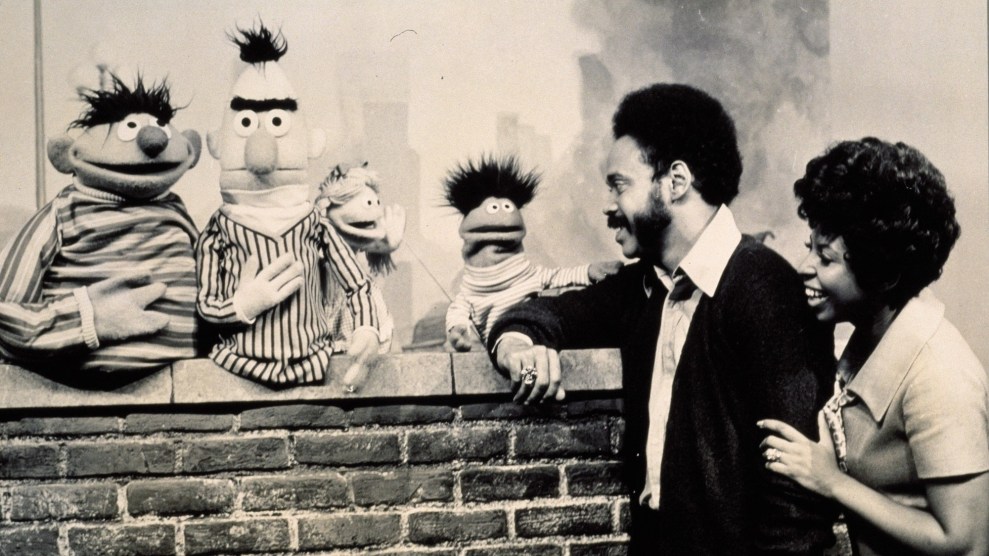

Sesame StreetAlbum/Entertainment Pictures/Zuma

Welcome to Recharge, a weekly newsletter full of stories that will energize your inner hellraiser. See more editions and sign up here.

Sesame Street is celebrating its 50th anniversary this year. The rush of stories and social posts about the iconic children’s TV show has inspired numerous stories about Muppets and cast members.

Few, however, noted the role of Dr. Chester Pierce, a psychiatrist and Harvard Medical School professor who was instrumental to the show’s early development and vision.

In 1969, Pierce signed up to be a senior adviser to Sesame Street creators Joan Ganz Cooney and Lloyd Morrisett. The founding president of the Black Psychiatrists of America, Pierce blamed television for furthering racist tropes, but also saw the medium as an opportunity to break those stereotypes, according to Undark Magazine.

Sesame Street was originally conceived as a show that would bring remedial education into the homes of disadvantaged kids. But Pierce recognized the show’s potential and pushed for it to include a multi-ethnic “neighborhood” with people of color as role models. Amid the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., and the riots spurred by racial inequity, this vision seemed especially crucial.

Radical for its time, Sesame Street presented an integrated society where everyone was treated with respect. People of color, such as Gordon, the show’s teacher, and his wife, Susan, were authority figures. That reinforcing message was as important as learning the alphabet and numbers.

“Early childhood specialists have a staggering responsibility in producing planetary citizens whose geographic and intellectual provinces are as limitless as their all-embracing humanity,” Pierce said in 1972.

Pierce fought racism his entire life, including as a Harvard undergraduate, when he became the first black student to play in a major college football game at an all-white university south of the Mason-Dixon Line, at the University of Virginia.

Pierce died in 2016, but his spirit of inclusion lives on in the most successful children’s show of all time.

Readers, did Sesame Street help you think differently about race and community as a kid? Do you think its lessons stuck with you as an adult? Let us know at recharge@motherjones.com.

Here are some more Recharge stories to get you through the week:

- A singular kindness. She was at a Starbucks ordering a tall coffee with a pump of mocha. Then she saw a flyer asking for a kidney from a donor with her blood type: O-positive. Before she left, Catherine Pearlman decided she would sign up. Last month, she and her recipient, Eli Valdez, checked into Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center. Afterward, they wore matching “STRAIGHT OUTTA KIDNEY SURGERY” T-shirts, designed by Eli’s wife, Monica. Pearlman emphasized that while she helped Eli, she also said she did it to be true to her own ideals. “I can’t improve the lives of all who suffer. However, I can help one man have a better life,” Pearlman wrote in an op-ed. “I hope this one act moves others to find a way in their own lives, in whatever way makes sense, to perform their own acts of kindness.” (Los Angeles Times)

- Family transcends border. For much of their lives, Sarai Ruiz and her mom have tried to keep their family together. When Sarai was four, her dad was deported to Mexico. She and her mom, both US citizens, moved from Wisconsin to Laredo, Texas, then across the border to Nuevo Laredo, Mexico, while Sarai attended high school in Texas. When Sarai graduated in May, her dad was not allowed to attend, so she walked, in cap and gown, to meet him at the border bridge after her ceremony. “I knew my father would never see me walk to get my diploma, but today I’d thought I’d surprise him by crossing the bridge so he could see me with my cap and gown,” she wrote on Facebook. After the hug, captured on a Facebook video that went viral, her dad said: “Nobody could ever separate us, only God.” (CNN)

- Changing the language. When Meaza Ashenafi began fighting sexual harassment in Ethiopia, the term didn’t even exist in Amharic, the nation’s primary language. Ashenafi, a lawyer, decided to create the term. She began prosecuting those accused of it and building the nation she wanted to live in. When a new government took power in April and offered her the role of chief justice, Ashenafi warned her superiors she would push for more change. “I told them, ‘If they want business as usual, I’m not the right person for this job.’” (Christian Science Monitor)