The truth revealed itself slowly but insistently. In 2015, photographer Daniella Zalcman had traveled to Canada to document a public health crisis among the country’s Indigenous people, who had one of the world’s fastest-growing rates of HIV infection. As she interviewed subjects in Saskatchewan, Ontario, and British Columbia, she discovered another terrible detail. Almost every person she spoke to told her that, as children, they had been sent to a residential school for Indigenous youth. These schools were designed to forcibly assimilate Indigenous children—a system pioneered across the border in the United States. “I had never heard of residential schools before,” Zalcman says. “I was genuinely shocked that this entire 120-year-long chapter of Canadian history had been completely omitted from my consciousness.”

Zalcman set out to photograph portraits of adults who had been taken from their homes as children to attend the institutions. Her book, Signs of Your Identity, was published in 2016, but now she has expanded the project. With support from the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting, which funds underreported stories by independent journalists, Zalcman intends to document the forced assimilation of Indigenous people, particularly children, from 15 countries, including Australia, Norway, and Japan. “It was really important for me to make this a global examination,” Zalcman says. “This system is ongoing in many places around the world, including the United States.”

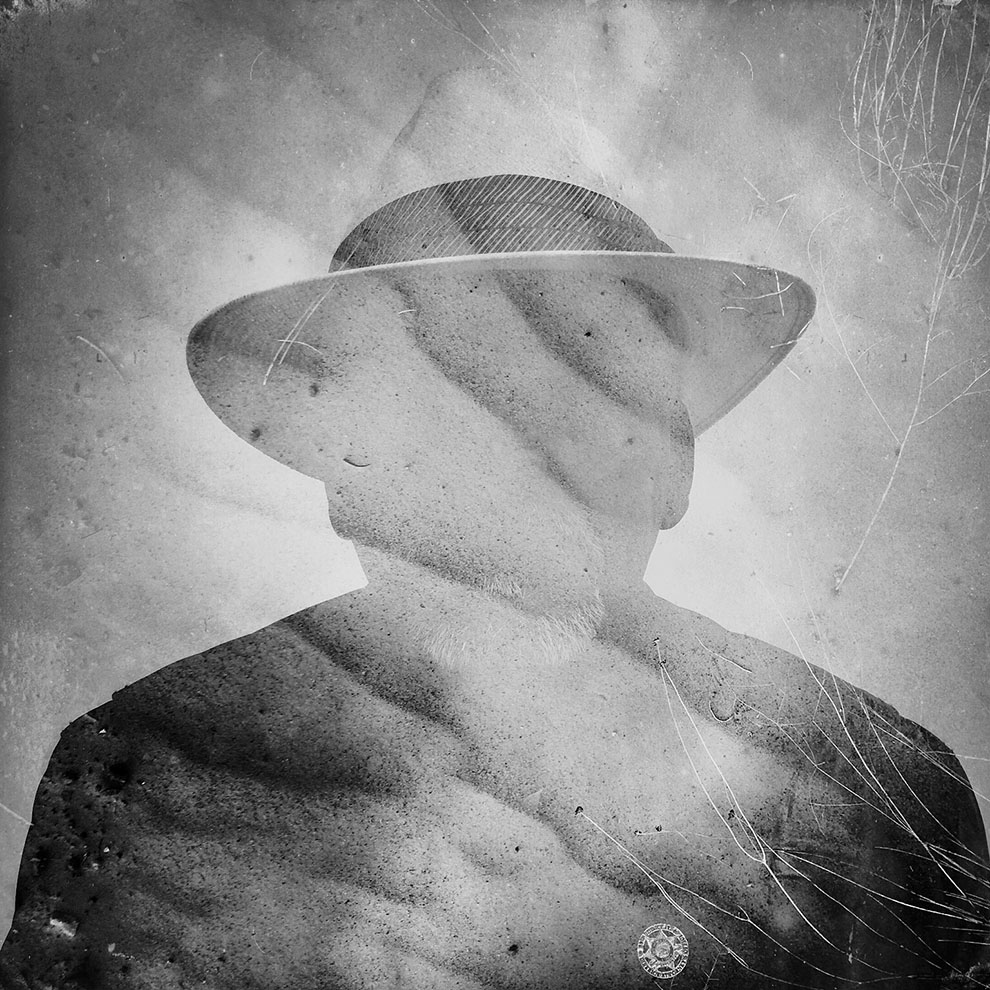

Pat Pumpkin Seed, Holy Rosary Mission, 1949-1960. “I got whipped constantly in school. Whipped for messing around in church, whipped for not praying, whipped for speaking Lakota with my brother. I always thought that was so stupid. All I want—all the Lakota have ever wanted—is to be allowed to be ourselves. We want our culture back. We want our language back. We want our ceremonies back. We want our lives back.”

Daniella Zalcman

Mother Jones: Tell us more about what you discovered in Canada.

Daniella Zalcman: Starting in the 1870s, the government created a network of boarding schools that were meant to forcibly assimilate Indigenous children into the dominant culture. A government employee, called an Indian agent, would show up on reserves and in Native communities, and effectively kidnap all of the kids under the age of 15—some were as young as two or three. Once they got to school, they were forced to wear Western clothing, their hair was often cut off, and they were punished if they spoke their own languages or practiced their own cultural traditions. There was rampant physical and sexual assault. In extreme cases, there was sterilization and medical testing. In Canada, the last residential school didn’t close until 1996, and the Canadian government didn’t issue a formal apology until 2008.

MJ: And the United States had a similar system?

DZ: We invented it! The first off-reservation boarding school was called Carlisle, in Pennsylvania. It was created by a US Army general named Richard Henry Pratt, and it became the model on which Canadian and American Indian boarding schools were based.

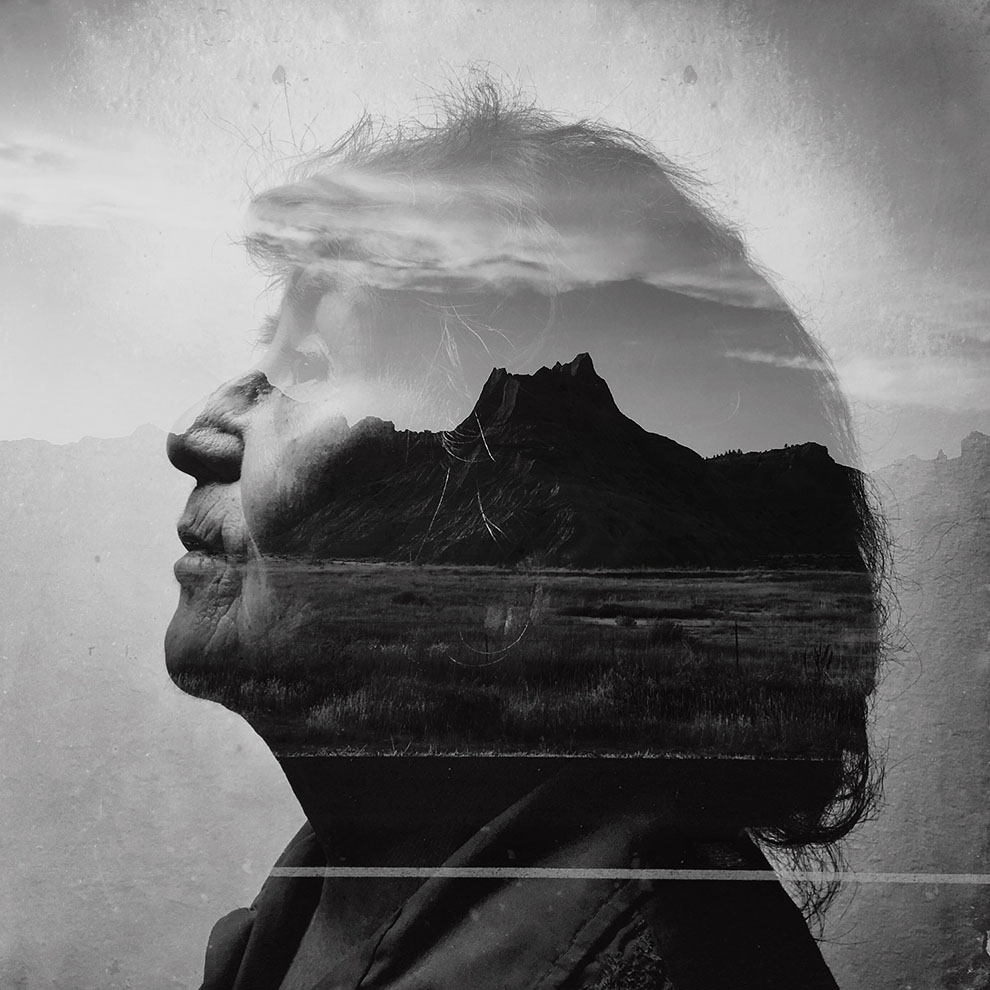

Oreos Eriacho, Ramah Elementary School (1961-1966), Ramah Dormitory (1966-1970). “Your spirit is kind of broken when you’re told you’re not supposed to act like a Native American. We’ve lost our identity out here. My kids ask me who we are and I have nothing to give them. But I’m teaching my daughters how to hunt, how to cut up the meat, how to use plants. I hope it helps. These two people in white shirts and ties come by the house sometimes wanting to talk about Joseph Smith, and I say, ‘Not today.'”

Daniella Zalcman

MJ: Tell me about your process for creating these portraits.

DZ: It’s all iPhone. I usually ask people if we can meet somewhere they feel comfortable, because these tend to be very personal conversations. I photograph everyone against a white backdrop. Then, based on our conversations, I’ll go in search of the physical place they were sent to boarding school. That’s where the secondary images come from.

MJ: Why did you decide to use multiple exposures?

DZ: My background is in spot news. But we’ve seen these photographs before, right? I don’t believe that those images always encourage our audience to feel empathy, or encourage us to think about the greater context behind that individual person’s life. To me, this story was fundamentally about ideas that I couldn’t literally convey—things like intergenerational trauma and cultural genocide. So I really felt like I needed to come up with a different visual language.

I believe that the story should mold the technique rather than vice versa, so now I’m working to develop different styles and strategies from country to country. One of the things we really need to question in the news photography community is the role of the outsider: How can we work more collaboratively with the people we’re photographing, and who are maybe positioned to be more informed, nuanced storytellers within their own communities? For the work that I’m doing in the United States, I’m partnering with three Indigenous artists—a beadwork artist, a painter, and an illustrator. I’ll be sending them some portraits and they’ll each produce 10 works that they’ll embellish.

MJ: You also co-run Natives Photograph, a database of Indigenous North American photographers that editors can use as a hiring tool. Given what you are trying to accomplish, is there tension in the fact that you’re not Native yourself?

DZ: It’s a hard thing. You could argue that if I’m trying to acknowledge that there are problems with my role as a non-Native storyteller in Native communities, maybe the answer is that I just shouldn’t tell those stories. I was talking to [Swinomish and Tulalip photographer] Matika Wilbur last night, and she said something that struck me: “When we use the word decolonization, it’s a metaphor. Because real decolonization is when the settlers actually leave. But we know that’s not gonna happen.”

In the mainstream media world, we have not worked hard enough to make space for Indigenous storytellers. I believe in the value of both insider and outsider perspectives, but if we are actively silencing the voices of one group of people, then we need to work harder to correct that imbalance. With Natives Photograph, I am trying hard to make sure that, while I do the work I do, I am helping to elevate the voices of Native photographers telling their own stories.

Wanda Garnier, Holy Rosary Mission, 1958-1963. “For years afterwards I’d wake up in a cold sweat, always from the same nightmare. The nuns were coming to take me back. Mother Edeltrude was standing over me and telling me we had to stay there the rest of our lives…Those women treated us like we were savages who had to be civilized. I thought we were pretty civilized, but I guess not in their books.”

Daniella Zalcman

MJ: You recently shot a story for National Geographic on the appropriation of Native identity in the United States. Talk about that.

DZ: This project is actually a direct response to the fact that I am a non-Native person who has started telling a lot of Native stories. I worked hard to make sure Signs of Your Identity is a nuanced and critical look at the system. For National Geographic, I wanted to take a more introspective look at what happens when non-Native people are responsible for creating an image of what Native people are. This work looks at the ways in which we continue to co-opt, misrepresent, and appropriate Native culture. Appropriation is a spectrum, and some of those things are much more harmful and violently racist than others, but I wanted to look at all of it as a system that is reinforcing.

From the beginning I knew I wanted to go photograph a Cleveland Indians game. I knew that I wanted to go to this re-enactment of the French and Indian War that takes place in Fort Niagara every year. I went to Ohio because I found out that while it’s one of the whitest states in the country, it has the highest number of Native-inspired high school mascots.

Some things I photographed were more serendipitous, or more personal. When I was a kid, I used to spend time in this little beach town in Delaware called Bethany Beach. At the entrance to that town there is a gigantic statue that the townspeople refer to as a totem pole. It’s supposed to be of a Native leader named Chief Little Owl. As a kid I assumed that this was some leftover relic from a long-forgotten Delaware tribe. It wasn’t until decades later, when I was working in British Columbia and Washington state, that I realized, “No, totem poles only come from the Pacific Northwest.” The statue in Bethany Beach was actually by a Hungarian-born sculptor named Peter Toth, who set out to complete one in every state.

MJ: Do you feel there is an urgency to your project now, compared to when you started it in 2015?

DZ: It’s always been urgent to me, because this is fundamentally about American identity. The ways in which we talk about, remember, and treat the first inhabitants of this continent have dictated the way we treat all people who are not in power, politically or economically. Look at the insanity that’s happening at our southern border right now.

We’ve never really come to terms with our own history. We don’t think of the United States as a country that was built by slave labor on stolen land. Until we have the ability to acknowledge that, to really understand this country in that way, I don’t think we’re going to be teaching our children an accurate reflection of who we are and where we come from.

Bessie Randolph, Albuquerque Indian School, 1952-1962. “Other people think for you. You have no time to think for yourself. When I got out, I didn’t know whether to go right or left by myself…It was the same every day for 10 years: Wake up at 5:30, clean the building and make the beds, breakfast from 6 to 7, report to the school building at 8, lunch at 12, out of school at 4, dinner at 5:30, asleep by 8. Ten years of following that routine and we didn’t know how to live like real people. We were told when and how to do everything. How do you apply for a job? How do you use the telephone? Are you supposed to go to college? Our parents thought that because they sent us to school we’d know what to do and where to go after, but we left school completely lost…I was lonely at school. I’d never been lonely in my life. I always had my family.”

Daniella Zalcman

DZ: My main goal with kids is to piss them off. I believe middle and high school students are humans at their most empathetic. They’re most likely to be able to change their worldview and their mindset. I want them to get mad; I want them to understand there are things that are fundamentally broken with how we tell stories, and how we codify which stories matter.

Most of the teaching I do is in classrooms that are predominantly black and Latino, and it is remarkable to see how quickly they understand how their own communities are affected by these exact phenomena. I tell them, “Look, you guys all have to be storytellers.” Storytelling is the fabric of our society. It’s how we learn, it is how we communicate, it’s how we remember. And if we are not able and willing and given the space to tell our stories, then we are learning an incomplete version of our own reality. We have so long allowed white men to dictate what we remember and forget.

MJ: When you were shooting for National Geographic, did you speak with the high school kids about their Native-inspired mascots?

DZ: In Ohio, several of the counties were as high as 98 percent white. I did talk to students, and I found that they’d never really thought about it before. It wasn’t that they had decided that they wanted to be racist—that’s never the starting point. It’s just that there had never been any indication that they should stop and think about this—that there might be anything wrong with it. I think that’s the worst thing that we’ve done with our relationship to Native people. We’ve made their identity and their trauma invisible.

Lisa Schrader, St. Joe’s Indian School (1974-1979), Red Cloud Indian School (1979-1982). “You know, healing requires acknowledgement. And when we were taken away from our homes and we lost our language and we lost our culture and we lost our identity, no one ever told us, ‘Welcome home. I’m glad you made it back.’ People need that, and they haven’t gotten that.”

Daniella Zalcman