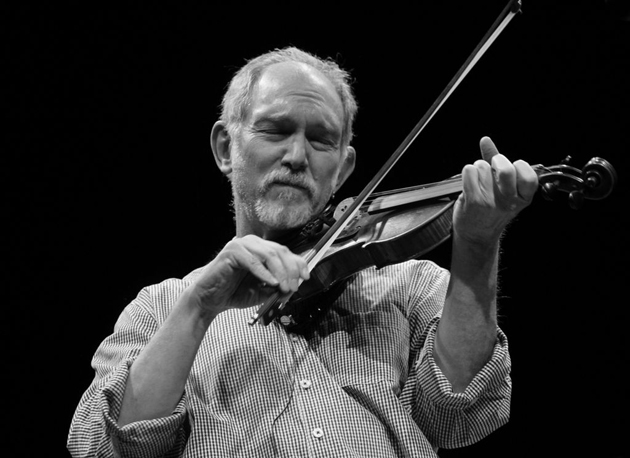

Spencer & Rains, self portrait Howard Rains

I really miss vinyl. And it’s not just the warmer sound and blah blah blah. It’s the marriage of music with visual arts—the flipping through the records (not scrolling or searching) to decide what you’re in the mood for. The ritual reading of the lyrics and liner notes. The wonder and mild envy you feel (at age 12) when you’re staring at Gene Simmons’ monster boots on the cover of the Destroyer album and cranking “Detroit Rock City” while your parents are yelling something in the background about would someone please just stop that infernal noise, but all you hear is that “mwa-mwa-mwa” sound the adults make in the Charlie Brown specials.

Which brings me to Spencer & Rains—nothing like Kiss or Charlie Brown, thankfully. My own musical path has taken me from classical piano and boychoir to blues and rock and funk, and then punk-rock drumming and whatever I could pull off on the guitar. My mom was raised in southern Vermont, where old-time music and square dancing remains a part of the local tradition, and so I grew up around some of that and when I got older I picked up a fiddle. (Profound apologies to my family.)

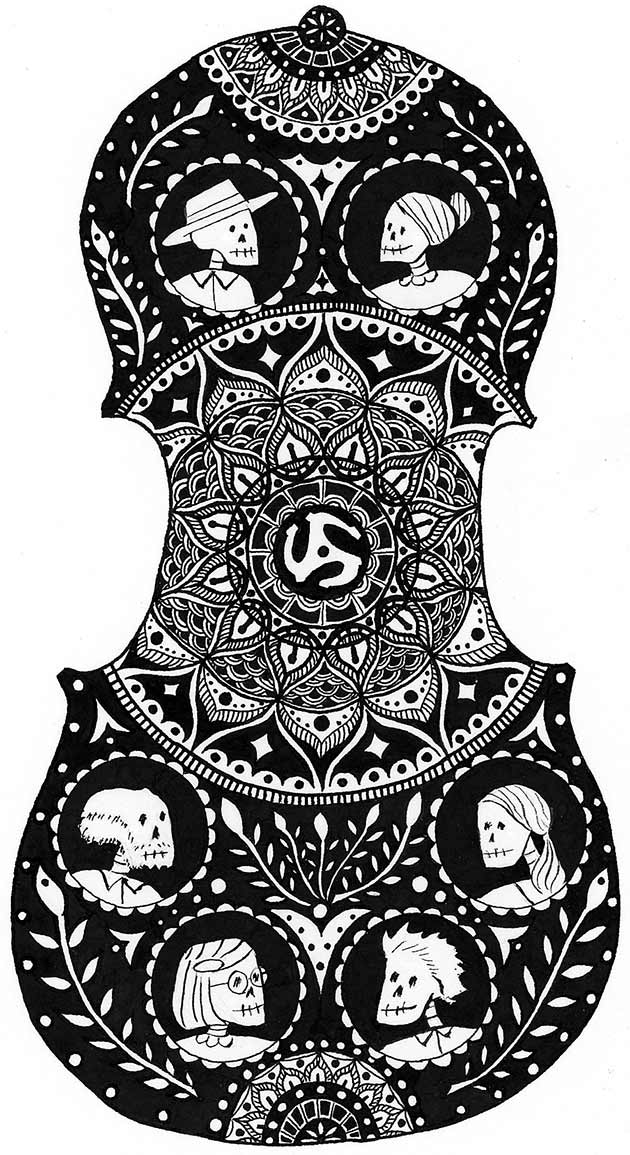

Cover drawing for “The Skeleton Keys.”

Tricia Spencer

So in 2016, when the people in my old-time music circles started bringing in songs from Spencer & Rains, who had a new album of old Texas fiddle tunes floating around, for some reason I pictured them as geezers who sat around on their front porch in rural Texas all day, jawing with the younger musicians who’d made a pilgrimage to hear their stories and learn from the masters in person. (Because that’s a thing.)

But it turns out I’d made that all up.

Not long after, at the opening night of the 2016 Berkeley Old-Time Music Convention, an affable chap named Howard approached to ask where I’d gotten my T-shirt. (It said “The Gods Hate Kansas,” one of my old punk bands.) He wasn’t a geezer (yet), but he was Howard Rains, and he was (and is) married to Tricia Spencer, another not-yet-geezer. They live in Kansas (where they sit on their front porch all day and…), which is why they were interested in my t-shirt.

The page for “Walk Around My Bedside” depicts Rains’ stepfather, artist Tony Bass, on his deathbed in 2015. Rains did all the portraits for the album. Spencer did the border work.

I’ve gotten to know Spencer & Rains a bit since then. I’ve learned tunes from them and jammed with them (very humbly) and watched them perform, and we’ve commiserated over the challenges of parenting teenagers. They both have fine voices and toggle skillfully between fiddle and guitar, while bass, banjo, ukulele, and other instruments are provided by their band, the Skeleton Keys. Rains was raised in Texas, hence his regional interest, and Spencer in Kansas, hence hers. Both have music in their blood—Spencer’s grandfather is the source of a bunch of her tunes.

What on earth, you ask, does any of this have to do with vinyl and Gene Simmons? Well, apart from the quirky selections of regional songs Spencer & Rains are keeping alive and their smart harmonies and the forethought they put into punctuating melody lines with well-placed guitar walks and twin-fiddle chording, one of the special things about them is their marriage of musical and visual arts.

Leadbelly

Tricia Spencer and Howard Rains

Now I sound like a geezer, but I hate digital music for its lack of that. Streaming has its merits, especially when you’re trying to track down a particular band or song to learn or listen to. But vinyl made things accessible in a different way. These days, to me, music can feel so out of sight, out of mind. There are too many choices to process—even within our own music collections. We have access to everything now, but when I was growing up, you could actually see what you had, right there in front of you. You might pull out Thelonious Monk’s Underground album, the one where he’s sitting at his piano in a room cluttered with curiosities—including what appears to be a taxidermied Nazi soldier. And then you read the notes, which claim that this is indeed a taxidermied Nazi that Monk brought back as a souvenir from World War II, and you realize he’s a total kook and you like him the more for it.

A gathering of friends inspired the artwork for “Big Powwow,” and also that oatmeal recipe.

Tricia Spencer and Howard Rains

With old-time music every song has a story, or at least a provenance, and so the musicians have to be storytellers, too. The stories are told in different ways. Spencer & Rains’ latest, The Skeleton Keys, packages a CD (remember those) in a letter-pressed cover containing a 40-page illustrated booklet—for each of the 17 tracks, there are biographical snippets about the composer or the song, or something about the context in which the tune was learned or about the people Spencer & Rains learned it from. (There’s even a steel-cut oatmeal recipe.) The collection, available from Old-Time Tiki Parlour, contains a mix of instrumental fiddle tunes and vocal tunes ranging from obscure to widely known. I prefer the surprises, and one pleasant surprise was the quality and extent of the artwork. Spencer specializes in intricate, iconographic pen-and-ink drawings, which buttress Rains’ fanciful watercolor portraits of musicians and song subjects.

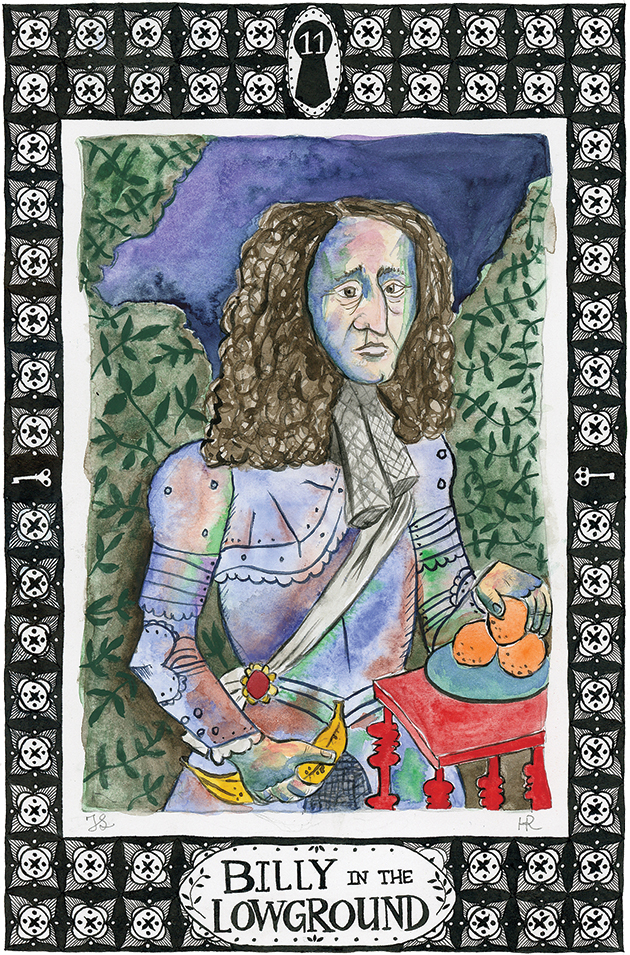

Willam of Orange. (Nice banana.)

Tricia Spencer and Howard Rains

And the stories are enlightening. I mean, who knew that the old fiddle tune “Billy in the Lowground,” which exists in many a version, was named for King William III of England (a.k.a. William of Orange), the subject of one Rains portrait. Or that Huddie Ledbetter (Leadbelly), whose “Where Did You Sleep Last Night” is covered evocatively on the album—I’m listening to it as I write—spent a portion of his youth in the Rains family hometown of Marshall, Texas, where Leadbelly received his first instrument, an accordion! Or that the protagonist who dies of a bullet through the breast in the mournful “Tom Sherman’s Barroom” died of syphilis in the original ballad, “The Unfortunate Rake.”

We get to know the musicians and their families and friends through the art, too. “Stony Point” came from Vernon Spencer, Tricia’s grandad, who after retiring from farming ran a gas station in Big Springs, Kansas, where there was always a guitar hanging on the wall and a fiddle sitting on the shelf, and a wayward musician could stop by and play a few. (Fiddle and banjo tunings are listed for every song, so you can give them a try if you’re so inclined.)

This tune from Texas fiddler John Wills is about Olive Oatman, a girl abducted by the Yavapai tribe in 1851 and traded to the Mohave, the source of her tattoo—and then traded to white settlers at age 19. She ended up in Rains’ hometown.

Tricia Spencer and Howard Rains

All and all, it’s an impressive effort—one that gives me hope that the future of recorded music will retain some of things we’ve given up in our quest for mobility and convenience. “We wanted something that felt like the days when you got an album and you couldn’t wait to have a quiet moment to listen to it,” Spencer told the crowd at a recent performance I attended, “and you got your special beverage out and dimmed the lights and you started reading while you were listening. We thought this might be our last attempt to create something like that.”

It needn’t be, though. It needn’t be.

The Skeleton Keys, from left: Brendan Doyle, Charlie Hartness, Spencer & Rains, Emily Mann, and Nancy Hartness.

David Bragger.