A popular Animal Planet reality show about a family-run zoo is going off the air, after Mother Jones presented the network with evidence of animal welfare violations dating back nearly 20 years—a decision the show’s creators said was connected to “new programming directions at the network.”

Yankee Jungle stars Bob and Julie Miner, a loveable, down-to-earth couple tending to 200-plus animals at DEW Haven, a roadside zoo outside Mount Vernon, Maine. “At this sanctuary, the animals are family,” the show’s tagline reads. But what audiences of the series—whose first season averaged 900,000 viewers—didn’t hear about was the zoo’s long record of animal welfare problems, conditions a state investigator once described as “deplorable” and “untenable.”

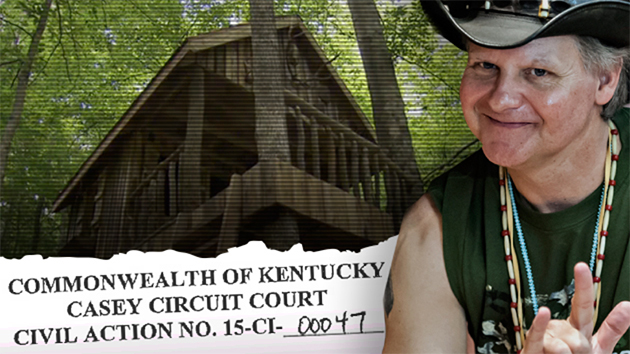

The cancelation of Yankee Jungle follows the network’s announcement in December that it would seek “to elevate the scientists” in its programming and cast its shows as more educational. In an earlier investigation, I documented alleged cavalier mistreatment behind the scenes of Animal Planet’s show Call of the Wildman. In that show, animals were procured or trapped so a rescuer known as “Turtleman” could chase them in tightly scripted scenes. The show, which never returned with new episodes after its fourth season in 2014, is still under investigation by the US Department of Agriculture.

“One day we just came in and looked at each other and said, ‘You know, no more bearded guys in the kitchen with fucking pigs running through the living room,'” David Zaslav, the head of Discovery Communications, which owns Animal Planet, told the Washington Post at the start of January. “Let’s get back to who we really are.” Rich Ross, the network executive overseeing Yankee Jungle‘s 2016 season, recently told the New York Times that “we can get ratings by doing things the right way.”

Mother Jones first approached Animal Planet and Lone Wolf Media, the production company in charge of the show, in January, after uncovering documents alleging that DEW had failed to comply with basic welfare rules on multiple occasions stretching all the way back to the late ’90s. DEW has also been cited for alleged violations in recent years—including after filming for the series began. That information has never been disclosed on the show. “The whole history’s ignored,” said Monica Hooper, a former DEW volunteer. “How can these people, who’ve gotten away with so much, have a show?”

More than 500 pages of government records and interviews with multiple former DEW volunteers reveal disturbing evidence. They also illuminate the difficulties that state and federal wildlife officials have with effectively regulating the nation’s private zoos. Allegations in the documents include:

1. State game wardens raided the zoo in 1998 after finding that the Miners had imported two black bears and a Celebes macaque—a primate listed as endangered since 1996—into Maine without proper permits. The Miners say they didn’t know the law at the time. They subsequently received permits for those animals.

2. Wardens raided DEW again in 2002, seizing animals that they said the Miners had again illegally imported into Maine, including an endangered ring-tailed lemur. The Miners say they had verbal permission from state officials at the time of importation and that they received paper permits before the raid took place. Most of the animals were ultimately returned to them.

3. According to USDA documents, the zoo failed to comply with multiple parts of the federal Animal Welfare Act and was cited for dozens of offenses between 2004 and 2015—including for poor sanitation, unhealthy feed, and improper enclosures.

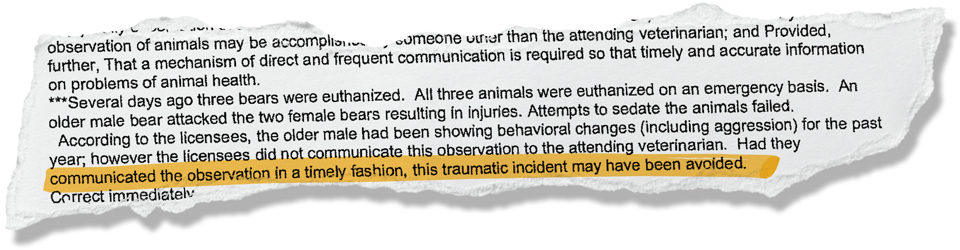

4. In 2012, three black bears at DEW had to be euthanized, an event that may have been avoided if the animals had received proper veterinary care, according to documents from the USDA. The Miners dispute that finding and say the bears received proper care from their vet.

The Miners have vigorously defended their record in emailed statements to Mother Jones. All past infractions were fixed quickly, they said, and no animal was ever in danger. The Miners argue a key state wildlife investigator was misled by a “disgruntled volunteer,” and they accuse the official of “unprofessional behavior” and “exaggerations.” Maine authorities say those complaints are “unfounded.”

After Yankee Jungle‘s second season wrapped at the end of February, DEW told its Facebook fans that it would be “taking a break from filming after two very intense seasons” but that it was “leaving open the option” to continue the show in the future. But Animal Planet confirmed to Mother Jones that the show has been effectively canceled. “It is not returning,” said Laurie Goldberg, a network executive. She declined to answer detailed questions about what Animal Planet did or didn’t know about DEW’s history. The show is still available on iTunes and Amazon.

Lone Wolf said in an email that it was informed in late February that Animal Planet had “decided not to order new episodes of the series.” The company added that the move coincided with the Miners “deciding not to continue on with Yankee Jungle as they would like to take a break and spend more time focused on their [animal] rescue efforts.”

During its run, Yankee Jungle made no mention of alleged violations that Lone Wolf’s own behind-the-scenes research turned up at the end of 2015—including the deaths of the black bears in 2012 and problems with the facilities found under the Animal Welfare Act in 2014 and 2015. A research report that the filmmakers commissioned from a wildlife expert generally praised DEW, but it also included reference to the state’s raid on the zoo and the alleged illegal importation of animals. Lone Wolf denies having any knowledge of the vast majority of incidents and allegations uncovered by Mother Jones. The company points to a USDA inspection conducted in January 2015, just before the filming of season two, that found no violations. (Federal inspection reports published months before and after the USDA inspection both documented violations.)

Instead, Yankee Jungle romanticizes DEW (which stands for Domestic Exotic Wild) as a hardscrabble but big-hearted operation. Bob Miner, a bearded Vietnam vet, is the Noah of this ark; we’re told the animals’ unusual affection is Bob’s therapy for PTSD and several strokes. Julie Miner keeps the nonprofit operation (funded by donations and ticket sales) afloat, while tending to young exotic animals inside the house. Both are local celebrities, showing off baby animals at a restaurant and battling Maine winters to ready the zoo for the tourist season. “These animals, they’re like our family,” Bob Miner says in Yankee Jungle‘s title sequence. “Sometimes I wonder if we rescued them or they rescued us.”

The Miners have plenty of fans. “We really don’t have a lot of animal places to take our children to, and this one gives them the sense of oneness with nature,” reads one letter to state wildlife officials urging them to support DEW. “I love watching Yankee Jungle,” reads a typical Facebook comment on the show’s fan page. “They are such great people to take in the animals that not many places want to deal with.” One commenter called critics of the show “misguided out-of-state vegans.”

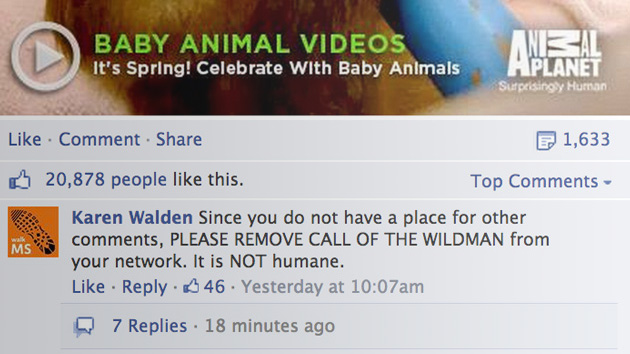

But elements of DEW’s checkered history have for several years been on the radar of leading national animal rights groups, which advocate greater regulation of zoos like DEW. Small-scale protests cropped up against Yankee Jungle after it premiered, fueled by a popular Facebook campaign, “Say no to Yankee Jungle.” Last year, activists staked out the production company’s offices in Portland, Maine, and delivered a 100,000-signature petition to Discovery’s headquarters.

“It’s irresponsible for Animal Planet to give a platform to operators who are in the business of exploiting animals while purporting, at the same time, to be a network that cares about animals,” said Carney Anne Nasser, senior counsel for Animal Legal Defense Fund.

The Miners deny any animals were exploited, and Lone Wolf calls the activists “internet bullies, engaging in an unfair trial by social media.” In response to the protests, Jed Rauscher, a Lone Wolf executive, reassured a Facebook fan last year by writing, “Luckily, those who love the show far outweigh its critics.”

Still, Lone Wolf commissioned its own report from a wildlife biologist in September 2015. The report acknowledged the problems recorded by the USDA at DEW since 2012 but called them “benign.” It slammed the animal rights movement as a “radical ideology” that relies on “false and unsubstantiated allegations of animal abuse or non-existent problems to raise funds, attract media attention and bring supporters to the movement.”

Animal Planet also ran “thorough” background checks on the Miners and other cast members, Rauscher said, but did “not find any violations or issues that would prevent the show from moving forward at that time.”

“During filming, the production company was confident that DEW Haven was operating completely lawfully and ethically, as we believe it continues to do today,” he said.

48 Violations

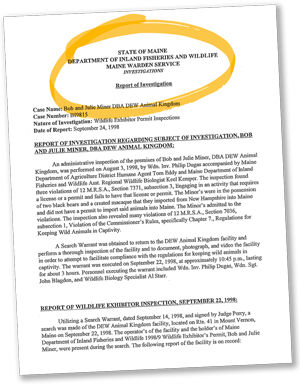

Maine wildlife officials keep a lengthy and disturbing file on the Miners and their roadside attraction, including hundreds of pages of documents released at the start of 2016 to a New Hampshire animal rights activist, Kristina Snyder, under the state’s freedom of information laws.

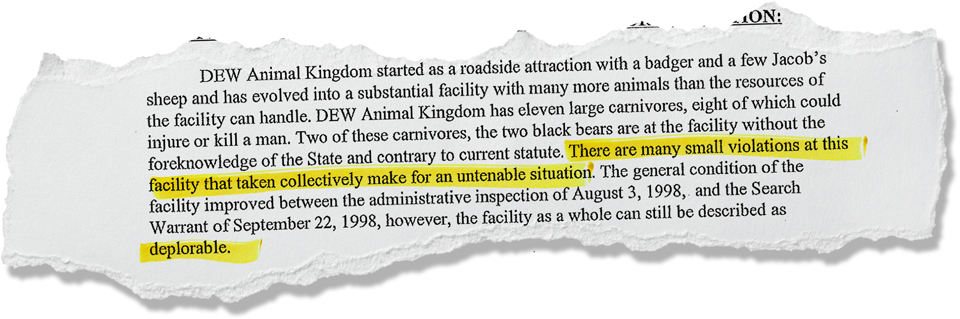

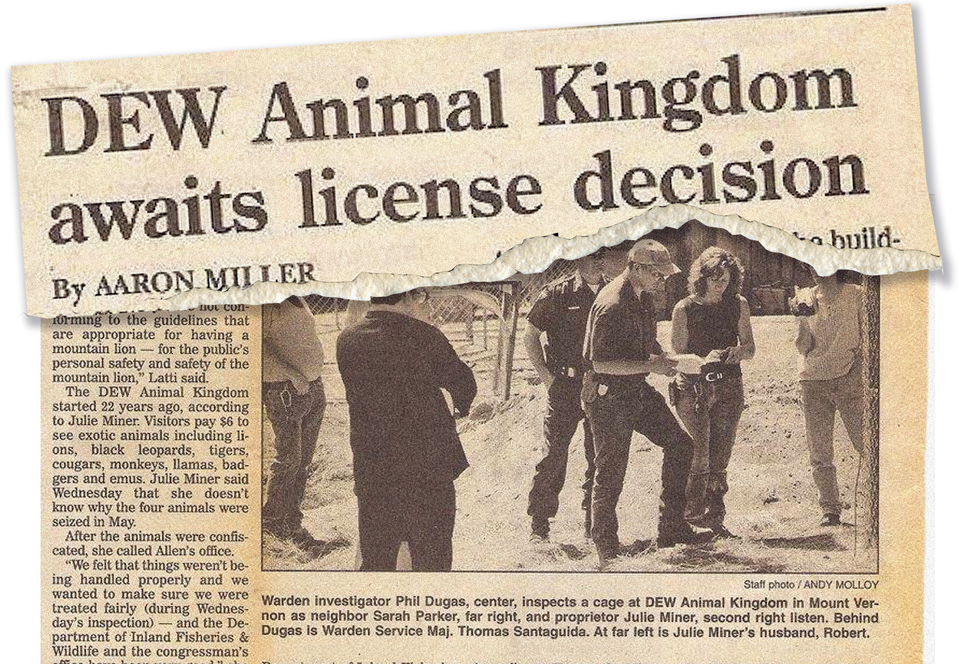

As early as August 1998, Investigator Warden Philip Dugas from the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife recorded “deplorable” conditions at the zoo, with “many more animals than the resources of the facility can handle.” Dugas alleged that the Miners weren’t complying in many cases with state laws requiring clean, fresh water. He also wrote that the Miners had imported animals into Maine without proper permits, a violation of state law. The Miners say they didn’t know the law at the time. They applied for permits after the fact and received them.

Dugas executed a search warrant to raid the zoo. His internal report was scathing, listing 48 individual violations. “There are many small violations at this facility that taken collectively make for an untenable situation,” he concluded. Authorities suspended DEW’s exhibitor license for 90 days. The Miners made the required changes and were allowed to resume operations.

Meanwhile, federal inspectors were also scrutinizing the zoo. In March 1998, a USDA veterinarian witnessed injured animals, potentially unwholesome feed, and dangerously broken fencing. The USDA launched an official investigation and eventually fined the Miners $4,500, which they paid. The Miners say they fixed all the problems the USDA identified.

Authorities have limited power to police facilities like DEW. The federal Animal Welfare Act, administered by the USDA, requires zoos to meet certain minimum requirements for sanitation, veterinary programs, and safety. But animal rights groups say the USDA doesn’t have enough resources to effectively monitor all of the nation’s captive wildlife. Of the roughly 5,000 tigers in America, for example, “the overwhelming majority is in the hands of private owners who aren’t being inspected by USDA,” says Nasser, the Animal Legal Defense Fund lawyer. Nasser estimates that most of the tigers that are inspected are in roadside zoos such as DEW.

“This nation is currently facing an epidemic of unqualified individuals and facilities possessing dangerous wild animals, which threatens both public safety and animal welfare,” wrote the Humane Society of the United States, alongside other top welfare groups, in a 2013 petition to the USDA urging tighter regulations and greater oversight.

What’s more, USDA fines and citations often amount to slaps on the wrist—something also criticized by the department’s internal auditor. “The result,” says Debbie Leahy, the manager of the captive wildlife protection program at the Humane Society of the United States, “is these fines are so small that places just consider them as a cost of doing business.”

Thomas Santaguida, Maine’s deputy chief game warden at the time, acknowledged that state officials were slow to act in the Miners’ case. Santaguida, who has since retired, blamed the delays on limited manpower that made it difficult to do a complicated job effectively. “I can remember going, ‘We have basically ignored these people for years,'” he said in a recent interview.

Authorities swoop again

Strapped for resources, wildlife officials around the country often rely on whistleblowers to alert them to potential problems. That’s what happened when a former DEW volunteer named Monica Hooper took her story to Maine officials in 2001.

Hooper asked me not to say exactly where she lives—she’s scared. In 2004, a judge issued a temporary restraining order against Bob Miner, telling him to stay away from Hooper, after she told a district court she’d had a scary encounter with him at a supermarket. (The Miners and Hooper both say Bob Miner was never served with the order, and Hooper eventually dropped the case.) “Bob Miner has a very bad temper,” she told me when we met in her picturesque, snow-buried town.

In 1981, Bob Miner was convicted of several felony charges, including theft and burglary, and in the mid-’90s he was found guilty of possessing a firearm as a felon and receiving stolen property. In 1994, he was fined $25 for assault.

The Miners say Bob has “overcome many obstacles in his life, and has become a productive member of society who benefits hundreds of animals and people.” Lone Wolf says it didn’t know about Miner’s convictions before or during the production and that Animal Planet’s own checks didn’t turn up any “violations or issues” concerning enough to call off production. The Miners say that “Bob’s record is public knowledge and he has never tried to hide the hard past he came from.”

Bob Miner also doesn’t hide his dislike of criticism by his volunteers. “I just can’t see how people can come in here and tell me they want to volunteer and tell me how to do it,” he said in a 2014 documentary about DEW called Wild Home. “If they’re so damn good and know so much about it, why didn’t they start one themselves?”

Hooper is the only former volunteer I spoke to who was willing to put her name on the record. A social worker in her mid-30s, she sat in her grandmother’s creaky rocking chair as we talked.

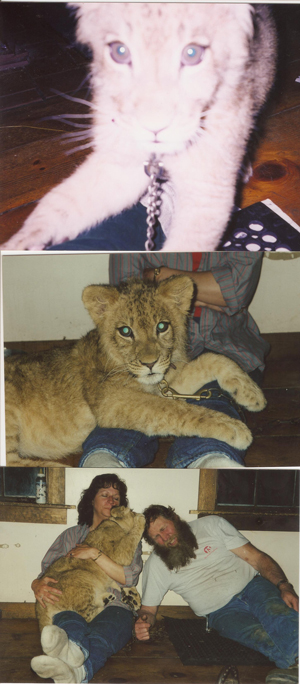

Her experience with the Miners dates back to 1999, when she was 19 years old. After her former employer, a traveling zoo in Pennsylvania, was forced to shut down, she was given a homeless baby mountain lion for safekeeping—something she later admitted to authorities had occurred without the proper permits. After keeping the cat in her house for a couple of days, Hooper took it to the Miners’ operation, then called DEW Animal Kingdom, for a more permanent home. But bringing wildlife into Maine requires a permit, and neither the Miners nor Hooper had received one, according to a signed affidavit by Investigator Dugas. The Miners dispute that allegation.

Photos of the silver-coated cat, named Squeaker, are still hanging everywhere in Hooper’s wood-paneled living room. “I would go out and see him every week,” she said. Eventually she began to volunteer formally.

But the longer Hooper stayed at DEW, the more distressed she became about what she witnessed there. “I’ll never forget it,” she said. “It cuts me right to the core.”

As her relationship with the Miners deteriorated over several months following her complaints about Squeaker’s care, Hooper began photographing the stomach-churning conditions she says she witnessed at DEW. In one photo she showed me, flesh and rotting hooves are seen stuffed into overflowing buckets. Another reveals heaps of dead cows—apparently discarded on the property after being used as feed. “They would take some meat off and let the rest rot,” Hooper explained to me. “They ended up with this big mound of rotting animals.”

The photos show excrement-smeared cage floors and animals looking at bowls full of foul water—or bowls that are bone dry. “That really was a common theme among the animals,” Hooper said. “They were really thirsty. They did not have water. They didn’t have proper food.” The Miners say their animals “have always had proper housing, fresh food and water.”

The Miners deny that Hooper’s photos are authentic. “These pictures were not taken at DEW Haven,” the Miners told Mother Jones, despite the fact that many show buildings that can also be seen in Yankee Jungle and Wild Home.

In 2001, Hooper presented some of her photos to Maine’s wildlife investigators. In an investigation report, Dugas wrote that he believed “without reservation that [the photos] depict the DEW Animal Kingdom as I have been to the facility on numerous occasions.” When asked by Mother Jones whether state officials stand by the assessment that the photos were taken at DEW, a spokesman for the Maine Department of Inland Fisheries and Wildlife responded, “Yes, the statement by investigator Dugas speaks for itself.”

Keel Kemper, the wildlife officer who interviewed Hooper, promptly registered distress in an email to colleagues: “I hope we can all agree to shut this operation down and to proceed with this action ASAP,” he wrote.

Kemper was especially concerned by one of Hooper’s photos taken in 2000: a three- to four-month-old lion cub shown tethered by a chain to the floor inside the Miners’ home. Maine law states that “no animal shall be chained or otherwise tethered to a stake,” though the Miners point out that there are exceptions for supervised training, grooming, and veterinary care. It’s unclear which of those exceptions would have applied in this instance.

Several photos over the years—and even images from the television show Yankee Jungle—show the Miners regularly kept lion cubs and other animals inside their home. They were cited once by the USDA, in 2005, for keeping a lion cub in the house; the citation said the animal should be kept in a proper enclosure that conforms to the Animal Welfare Act. Screenshots taken from a Facebook video, dated this past January, show a lion cub inside the Miner’s home, playing one on one with a human baby. The photo is of the Miners’ granddaughter, the couple says, “present during a routine feeding session.” The Miners say the animals kept inside their home were always “housed properly and in proper enclosures.”

Hooper left her meeting with Kemper in 2001 convinced that her evidence would lead to something. “I worked very hard,” she said, staring at documents and letters to wildlife officials covering her dining room table. “I really thought I had them.”

State officials geared up to move on DEW again. Crucial to sparking a new investigation was Squeaker, Hooper’s mountain lion housed at DEW. Dugas said in an affidavit that the Miners lacked the proper permits for his importation into Maine. The Miners dispute this.

Four animals—three mountain lions (including Squeaker) and an endangered lemur—were seized.

Squeaker was returned to an overjoyed Hooper. A vet described one of the other mountain lions seized from DEW as “crippled” from a botched declawing—a “butcher job,” according to Dugas’ account of the vet’s assessment. According to the vet’s medical report, the procedure left the animal unable to walk. Declawing procedures were legal at the time, but they were prohibited in 2006 under the Animal Welfare Act, “since they can cause considerable pain and discomfort to the animal and may result in chronic health problems,” according to the USDA. The Miners admit the cat had been declawed by their vet while in their care. They say this was “the one and only time we did have a cat declawed, and sadly he was diagnosed with phantom pain by our veterinarian.”

During this raid and follow-up inspections, state wardens continued to paint a picture of squalid conditions at DEW that, Kemper found, were “unacceptable to any reasonable person.” Kemper wrote in an internal memo, “I observed bones, heads, [and] hides cast randomly about the property.” He added, hyperbolically, “A dead, bloated calf with approximately one billion flies was observed, just south of the camel pen.”

Tensions erupted. The Miners filed a formal complaint against Dugas, claiming he had exaggerated his findings and that Hooper had misled him. “Our complaint was founded and appropriate action was taken,” the Miners say. But Mark Latti, the current spokesman for Maine’s wildlife department, disputes that. “The complaint was reviewed and determined to be unfounded,” he said in an email. Dugas was eventually removed from the case to ease the apparent personality clash, according to Santaguida, the former deputy game warden. But Santaguida says Dugas’ findings were solid. The department, for its part, continues to stand by Dugas’ work.

The Miners downplayed the findings publicly, as well. “Whenever you have any state or federal inspection, when they come in, nobody is 100-percent compliant,” Julie Miner told a reporter from the Kennebec Journal at the time. “I don’t care if you are a restaurant or a newspaper, they’ll find some issues.” The carcasses, she noted, were kept in a private part of the facility, separate from the exhibits. According to the paper, she added that DEW would “no longer take in animal carcasses.” (The Miners say the latter comment was actually a misquote. The journalist, Aaron Miller, disputes that, and the couple admits they never asked the paper for a correction.)

DEW’s website currently states that “most” of the facility’s meat is still “donated from farmers who lose cows and other livestock, and we pick up road-kill.” And Yankee Jungle shows footage of Bob Miner loading roadkill into his truck. The Miners say all carcasses were “disposed of under the state guidelines” adding, “We have always fed fresh carcasses at our facility, as it is the most nutritional way for the carnivores to eat.”

Around the same time, the USDA faulted the Miners yet again, slapping them with a $1,000 fine. In inspection reports, federal officials cited the zoo for offenses including not keeping different animal species apart, as required by law, and for unsanitary conditions, including a “drum of a liquid and bone mix”—discoveries that, in the words of Dugas, left the USDA inspector “visibly upset.” (The drum, the Miners say, was used for processing animal skulls to be used as art. They say the zoo animals were kept away from it.)

Persistent problems: three dead bears

The Miners say they heeded the order to improve. That’s true, at least after the 2002 blowup with authorities. “Every non-compliant situation was corrected,” Julie Miner told the local press at the time. A veterinarian who inspected the facility at the time observed that the animals had plenty of water and that the area where the carcasses once were had been cleaned up.

Santaguida agrees that the Miners made huge improvements. “They’re serious about those animals,” he told me. “They’ve given their whole lives to that place.” Lone Wolf shares that view: “Our experience has shown Bob and Julie to be thoughtful, devoted caretakers who have made great sacrifices in order to care for their animals,” Rauscher said.

Officials allowed the zoo to continue running public wildlife attractions under strict conditions, including quarterly inspections. Except for Squeaker, the state also returned the seized animals.

But serious problems soon returned to DEW. Routine inspections uncovered dangerous conditions even after Yankee Jungle began filming at the property—including electrified lines that weren’t activated and tiger enclosures that were improperly secured. In total, federal records show that from 2004 to 2015, the Miners were cited for 54 individual instances of noncompliance with the federal Animal Welfare Act—including for below-grade facilities, sanitation problems, and animal care issues. The most recently available USDA inspection, from July 2015, recorded problems with the enclosures for the Miners’ goats, sheep, and camel.

The Miners’ USDA license is active, and they add, “We are in good standing with both State and Federal entities.” They say they fix all problems as they arise.

In October 2012, the USDA learned that two young female bears at DEW were not getting along with an older male bear they were housed with. Just a month later, all three bears were euthanized after the male attacked the two females. A USDA inspector cited the Miners, saying the bears might not have died if the Miners had told an attending vet, as the law requires, about long-standing aggressive behavior from the male, something biologists call “stereotypic behavior” among bears in captivity. The Miners dispute the USDA’s citation, saying the behavior began during the bears’ breeding season, not a whole year before the deaths, as the USDA alleged. The Miners say they contacted a vet as soon as they saw the bear’s behavior change. The Miners also say they subsequently sent a letter to the USDA from their veterinarian saying the bear was under the vet’s care. Lone Wolf says it was aware of this incident. “We have neither the animal behavior [knowledge] nor the regulatory knowledge to dispute the USDA’s findings,” said Rauscher, the Lone Wolf executive.

DEW’s animal handling practices were again called into question in 2014—after Yankee Jungle had begun filming—when the Miners publicly celebrated the birth of three Bengal tigers and sold $50 tickets to bottle-feed the cubs. The Bangor Daily News reported that the sanctuary had 148 people on a waiting list for the “tiger encounter.” Both state and federal officials told the Miners to stop immediately because it could expose the cubs’ undeveloped immune systems to diseases. The Miners complained to the department that banning the shows meant lost revenue and educational experiences. “They were disappointed, but they complied,” said Jim Connolly, a director at Maine’s wildlife department. The Miners subsequently told Mother Jones that they were unaware of the state’s policy at the time. Rauscher said he read about the incident in the news but had “no first-hand knowledge” of it, adding that they had finished filming that year’s episodes weeks earlier.

“It’s supposed to be pro-animal”

Meanwhile activists like Kristina Snyder are hailing the show’s cancelation as a success. “Animal Planet—it’s supposed to be pro-animal, for animals, good for animals,” she told me in a recent interview in Portland, Maine.

For her part, Hooper still can’t quite bring herself to watch full episodes of the show, which she described as “karmically wrong.” But she welcomes the cancelation: “A milestone? Definitely!” she said in an email. But “not the end of the story.”

“The saga will continue, just not under international media spotlight.”

Correction: An earlier version of this story misstated the location of Monica Hooper’s former employer.