<a href=https://www.flickr.com/photos/xavierwilkinson/14665394675/in/photolist-okVYUk-hcTE9V-fqwPnh-57kHCn-zohfj-dRY9Xc-bBeqaD-eficEY-rF1nEY-4VFTzH-psj14c-9AS5Wf-wnsgMx-oamNnS-bojvSL-6HGtXE-bBepZZ-bojwj3-bBeqCF-bBeqsx-bM7fJM-zobKW-apMVgc-bpFLge-p78CdM-p78Cg2-p79xqs-p79xwj-poBc2A-p78WFE-poCMKV-poBbJm-q7445B-oqrx9d-7vCAKm-eciZh5-pYcbRZ-5RXrsC-oYvDq5-mLgJTz-qsWSzi-fyCxU5-cfHLSd-ePxCAe-mDE7qm-uXhiD9-qSJqty-qrni1D-fejDH5-akKbdH>Joshua Livingston</a>/Flickr

In October, a small but dedicated internet faction urged people to boycott the new Star Wars movie. On Twitter, #BoycottStarWarsVII became a trending topic, with some people tweeting that George Lucas’ latest promoted “white genocide,” because the lead role is played by John Boyega, a black man—and because we see our first black Stormtrooper.

Racially charged outbursts from fans of science fiction and comics are hardly new. In the ’40s and ’50s, comics “were sexist, they were racist, you name it,” artist Jules Feiffer told Mother Jones last year, “and they kind of gloried in that.” In 2011, critics including Glenn Beck cried foul when Marvel Comics made Miles Morales, a black-Puerto Rican kid, one of several spin-off Spider-Men in alternate universes. The controversy escalated earlier this year, when Marvel designated Morales as the principal Spider-Man. A Sony Pictures licensing agreement, leaked via the big studio hack, revealed specifications that Parker be played by a straight, white, male actor. Marvel creator Stan Lee reinforced this idea in a June interview when he said Parker should remain straight and white. Some fans were incensed by a Twitter campaign to cast actor/rapper Donald Glover as Parker; the role ultimately went to Andrew Garfield, who is white.

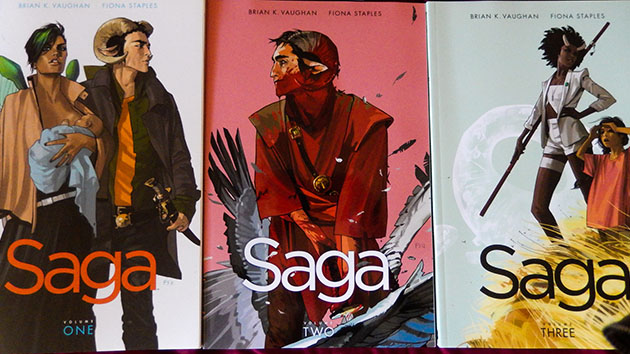

None of this has gone unnoticed by Brian K. Vaughan, an artist best known for his popular Saga series, not to mention his work on Runaways, the award-winning Y: The Last Man, and classics such as X-Men, Batman, and the Swamp Thing. In his own books, Vaughan, who is white, has made a concerted effort to feature people of color and queer protagonists. Saga is the story of an interstellar political conflict with an interracial family at its center. His most recent work is Barrier, a bilingual graphic novel that tackles immigration politics and includes entire scenes in Spanish. I caught up with Vaughan, the recipient of 10 Eisner Awards, to talk about comic trolls and his refreshing approach to the medium.

Mother Jones: Why do you suppose people who are willing to indulge fantastical worlds full of web-slingers and Jedis are so protective of those worlds when it comes to race?

Brian Vaughan: I don’t know, and I find it very unpleasant. I think some people are just very passionate that things remain the way they were when they were kids. Whether that means Spider-Man has organic webshooters versus mechanical webshooters, or he’s black or he’s white—they just love everything to be the way it used to be. I’ve never had any interest in retelling stories from my youth.

MJ: Is that why you choose to create main characters who are black women, say, or queer ghosts?

BV: [Laughs.] I like things that are weirdly imaginative and couldn’t be real, but I also like stories that are recognizable and relatable. With Saga, when I started, that wasn’t in the forefront of my mind. But I was talking with [illustrator] Fiona Staples, and I said, “There are these two characters, one has horns and one has wings.” Her first question was, “Well, do they have to be white?” I realized that for fantasy and science fiction, especially from my youth, white was the default. Luke Skywalker was in the lead, or even if you were a hobbit, you’re going to be white. That was an extremely old-fashioned, obviously really narrow-minded way to look at things. We don’t have to tell another sci-fi epic with two boring white people at the lead—let’s make them people of color. I think the book has been much better for it.

MJ: What made you want to write about immigration?

BV: Immigration confuses and terrifies me, so why not try to write a comic and make some sense of it? Marcos Martin [his co-writer on Barrier] and I had just finished doing the story of The Private Eye for Panel Syndicate. We wanted to try our hand at digital comics, in part because comics used to be this really inexpensive medium. Over the years, it’s become this really expensive hobby for just a few people. Privacy is one of the most important topics of the last five years, and it was really fun to be able to put out this comic and have it released in Russia the same day it was released in the United States and France, and sort of have this dialog begin. We wanted to tackle another big subject, and immigration will be just as important in the next five years, especially with the election coming up.

MJ: Do you get any backlash or hate email from the trolls over the inclusivity of your lead characters?

BV: I’ve never gotten anything but support and thanks from people for having diverse books. People just want good stories. But I can’t imagine how hard it must be if I was a person of color to see that kind of outrage on Twitter. I’d like to believe that humanity is, for the most part, pretty good, and I think that these are just a handful of angry weirdoes. I hope I’m right. Let me say this: To try and imagine that I’m another person is always going to be hard—whether I’m writing about a truck driver or someone who is gay, who’s trans, who is of a different ethnicity or creed. But it would be boring if I always had to write about myself and my limited viewpoint.

MJ: How did you choose to do some parts of Barrier only in English, and some only in Spanish?

BV: I’ve been fortunate enough to travel to comic conventions in Portugal, France, Canada, and it’s an honor to get to meet people from all over the world. But it’s also a reminder of what an “ugly American” I am, and how bad my language skills are, and the fact that I can only speak English. I see how much that separates and divides us. So yeah, this was a deliberate attempt to put out a book where we weren’t going to do any translations, where odds are, whether you speak English or Spanish or neither, you’re going to be lost at some point in this story. And that’s okay. We hope that by the end you’ll be able to understand what happened. It was the kind of thing we’d never be able to do as a TV show or a movie. You’d never be able to convince someone to give you money to do a bilingual story where you’re not translating half of it—you’d drive people crazy. But in comics, you can do whatever your heart desires.

Correction: An earlier version of this story referred to Morales as black-Dominican, not black-Puerto Rican.