Introversion Software

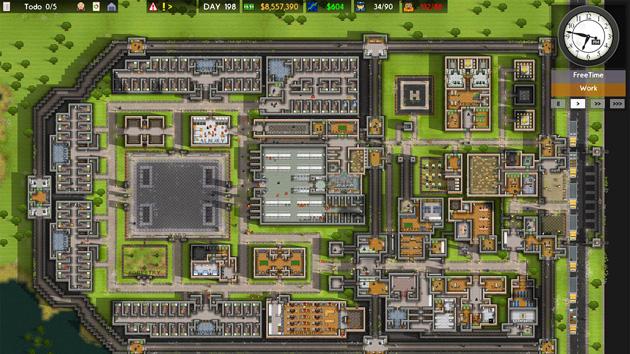

It’s late at night and I am staring at my computer screen, contemplating a decision: Do I go to bed or reorganize my prison so that medium- and maximum-security inmates go to chow and the yard at separate times? It would probably help bring the violence down. Or I could design a separate walkway from the maximum-security cellblock to the yard and put a fence down the middle to separate the dangerous from the more vulnerable inmates. This could easily take hours. This is why I swore off video games 15 years ago.

Around the same time that I quit gaming, developers Chris Delay, Mark Morris, and a couple of college friends began developing niche games in an industry dominated by blockbuster-driven companies with megabudgets. Their small, London-based company, Introversion, eschewed flashy graphics in favor of nuanced story lines and strategy. They designed a game about hackers and a sci-fi strategy game, Darwinia, which won the Independent Game Festival Award.

By 2010, the team was in a slump, and Delay took off on a vacation to San Francisco. During a tour of Alcatraz with his wife, the idea hit him: Why not design a game around a prison? Not an action-packed first-person shooter, but one where you play the CEO of a private prison company, tasked with designing, building, and managing your own lockup? Delay didn’t know much about prisons, but the more he researched—interviewing guards and former inmates—the more he realized they were ripe for the most complex of Sim City-style games.

Introversion, now with a staff of nine, spent the next five years designing Prison Architect. They released a beta version in 2012 and attracted more than 1 million players. It was their biggest hit, and they released the full version this month.

Like most simulations, the game has no real end point. The purpose is to delve ever deeper into a system you create, to wrestle with your own beliefs and morality in a fictional world whose mechanics bear a striking resemblance to real-life prisons.

Delay and Morris say they strictly avoided leading players to a particular moral conclusion. “We are not prison reformists,” Morris told me. “There is no agenda here.” This, ultimately, is what makes the game succeed. There is no secret trick to making your prison function well, and since you can’t really win, the very idea of what constitutes a successful prison is yours to interpret.

Prison Architect is not an easy game. Newcomers go through a “campaign mode” tutorial where they are thrown into a succession of five prisons and tasked with fixing various problems. The learning curve is steep—I probably spent 20 hours working through it—but subplots about mob assassinations, an execution, and a prison CEO burning documents during a riot create tensions to string you along.

The real game, however, is a blank slate. You are given a piece of land, $30,000, eight construction workers, and 24 hours (24 minutes in game time) before your first eight prisoners arrive. You can adjust how many you take in each day, but as with real private prisons, inmates equal revenue. And even if profit isn’t your motive, you need money to operate.

Inevitably, you begin with certain necessities. You need to contain your prisoners, so you lay a foundation for temporary holding cells. You need to hire a warden, and the applicants range from even-tempered to inflexible, politically connected, or corrupt. The warden needs an office with a desk and filing cabinet to work in. The prisoners need to eat, of course, so you put up a kitchen and hire a couple of cooks. You quickly learn from your mistakes—prisoners walk off if they are not fenced in; toilets don’t function without a water pump and plumbing.

It’s once you master the basics that things get interesting—do you want to build a Scandanavian-style model of reform or a totalitarian hellhole? Do you want to take a stab at remedying the challenges of the US prison system, figuring out how to manage maximum-security prisoners without solitary confinement?

I decide to invest heavily in rehabilitative aspects. I make the cells spacious and well furnished. I put pool tables in common areas. I prioritize visitation and a library. I build a classroom and start up basic education, drug addiction treatment, and job training. The deeper I get, the more I find myself thinking like a prison bureaucrat. I stop paying attention to the particulars of each inmate’s rap sheet and hire a psychologist who gives me reports on the population as a whole, measuring everything from overall hygiene to spiritual fulfillment. Morale, I am happy to note, is high.

But then things start to slip. More prisoners are coming in than I have cells for. I need a new cellblock, which involves running electricity to the building, constructing cells, bringing in beds, building a day room, and more. As my workers build, I notice that prisoners aren’t getting enough food. Are there enough tables in the canteen? Do they need more time to eat? More cooks? Someone gets bloodied in the shower room. Should I assign a guard to watch over it from now on? Should I shake down the whole prison to get rid of any weapons? In focusing on prisoner well-being, I’ve neglected my staff, which is now getting exhausted. Should I build a break room and hire more guards so they aren’t so overworked, or invest in surveillance cameras and lay some off?

Before I know it, my growing list of issues has put the inmates on edge. One shanks a fellow prisoner in an overcrowded holding cell. Another has a hammer—did I not have enough guards in the workshop? A riot breaks out. The holding cell catches fire and the inmates run amok, killing guards and each other. Someone offs the chief of security—I didn’t give him a locking door!—which means I can’t give guards orders until I hire a new one. I call in riot police and the fire department. When things start to calm, I build a mortuary for all the bodies and decide I need to hire a dog patrol and maybe turn my new chapel into an armory.

This is just the drift of my particular game. I learn that security lapses will lead to problems no matter how well you treat inmates, but tough-on-crime players will quickly find that denying privileges or raising the stakes for parole makes for a rowdy prison. They can beef up security, sure, but at some point they will realize money can only buy so many solitary cells. Inmates in the hole can’t do grunt work around the prison, so they will need to hire more janitors and cooks. They will also need extra guards to bring food to inmates who aren’t allowed to go to chow. Sooner or later, they might need to reconsider their approach: Should they just let it slide when inmates get caught boozing or hiding cigarettes?

Prison Architect is amazingly intricate, but the gamification creates certain falsehoods. Real private prisons, for example, aren’t rewarded when inmates get released. In real life, the only practical incentive for giving prisoners meaningful things to do is that it tends to keep them calm. Companies don’t get more money for turning out prisoners who don’t go back to crime.

There are also some major omissions. Race is functionally meaningless in Prison Architect. Morris says they were wary of “playing lip service to the issue,” though he is considering how race might be integrated into a future version. Inmates could be assigned traits like race, sexuality, and religion, and a small bias could be built into the game, he says, that makes prisoners congregate in communities that match their identities: “Once you’ve got that congregation occurring, it might be possible to model hatred.” A particularly hateful inmate might be prone to attacking members of another group, which could spark events like the race wars that have broken out in real US prisons. This would offer the player a new set of conundrums: Do you segregate by race? Lock the more hateful inmates in solitary? Try to create programs to help lower prisoner aggression while making sure inmates don’t run into someone they might stab in class?

The game makers say Prison Architect wasn’t based on any particular prison system, but I find it hard to come up with a prison that veers very far from a US-style lockup. Even when I get better at controlling the population, my reform-minded prison quickly goes bankrupt. Large cells and sweeping rehabilitative programs are expensive, so when my government grants run out, I have to shut down classes and drug treatment. I lay off guards and start serving worse—cheaper—food. I ponder whether I should build a shop and train inmates to make license plates to bring in some revenue.

Herein lies the message: Prisons are just one piece of a larger system. How they are operated makes a difference, yes, but they exist within the constraints of budgets, legislation, policing, and the conditions that drive people to crime. As long as those remain the same, competing philosophies about prison management won’t amount to much more than tinkering, figuring out how to squeeze a dollar late into the night.