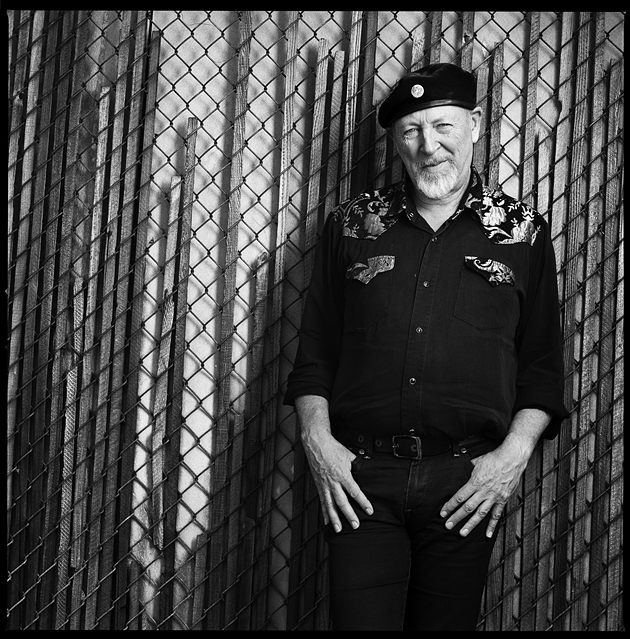

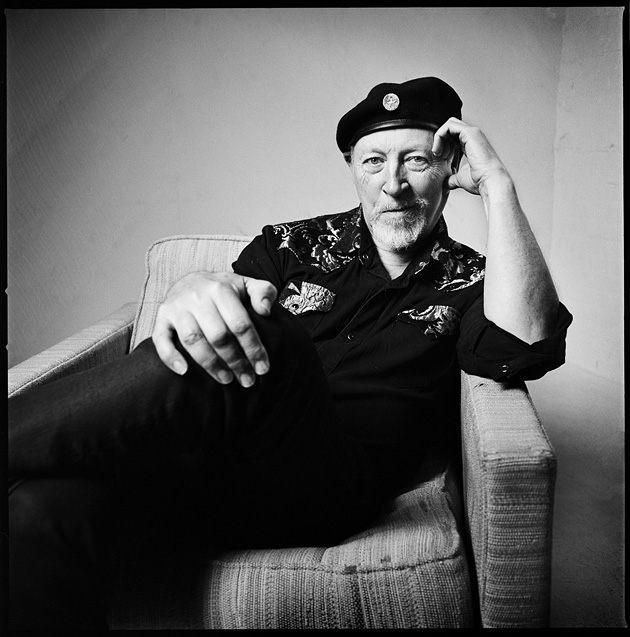

As guitarist and songwriter Richard Thompson, 66, was coming of age as a musician in 1960s England, the majority of British rock bands tended to cover and repurpose American rock and roll and R&B. With their 1967 band Fairport Convention, Thompson and fellow bandmates instead chose to draw from Britain’s own history—its broadside ballads, field recordings, and social and religious tunes. The result was a new “folk-rock” hybrid grown from British soil.

Throughout his career, Thompson continued to incorporate distinctly British sounds in his songwriting and guitar playing. Following five albums with Fairport and an interim solo record (featuring the artist dressed as a fly on the cover), Thompson recorded five studio albums with his wife, Linda, including 1974’s luminous I Want to See the Bright Lights Tonight. After their separation in the early ’80s, (their turmoil laid bare on 1982’s Shoot Out the Lights), Thompson continued with a steady output of excellent solo albums, including such highlights as 1991’s Rumor and Sigh and 1999’s Mock Tudor.

Released in June, Thompson’s 15th solo studio album, Still, was produced with an unobtrusive hand by Wilco’s Jeff Tweedy. The album features Thompson’s signature wry and reflective songs, and his stunningly original guitar work.

I spoke with Thompson when he came through New York on his current tour, which continues in the United States and Europe through October.

Mother Jones: From Fairport Convention to the duo with Linda Thompson and your solo work, how did your approach to music and songwriting change?

Richard Thompson: I started out being happy in a band. Like many others, we started out as a cover band but were very fussy about the covers we did. We were into lyrics. We’d find obscure stuff like Ewan MacColl songs and Richard Fariña songs. We covered Joni Mitchell’s songs before even she recorded them.

At a certain point we thought that to be taken seriously by our audience, we needed to be writers. That was a shift that probably started with the Beatles. They were the first band to do everything and they presented a new paradigm for people to aspire to. After them, everybody had to become writers or your audience didn’t take you seriously. “What’s your voice? What are you saying?”

We became collective writers; even if we were writing as individuals, we were writing for the band. We wrote about universal things, or about a band experience, or something very obscure, which was quite permissible in 1967. We were quite influenced by the Band, and the way Robbie Robertson and the other band members could write about their mutual experiences on the road.

When I write for myself, sometimes as an exercise I think, “I’m going to write a song for somebody else—a friend of mine, or a famous singer.” It’s kind of projecting someone else’s blueprint onto the song. But then if it’s a good song, you end up keeping it for yourself.

MJ: Most of the British bands from the ’60s used American R&B and blues music as their primary template, but it seemed very central to Fairport to embrace the history of British music. How did that evolve?

RT: At the beginning, the band followed the money. If there was a job at the blues club, we’d become a blues band. But we’d be doing the most obscure blues stuff we could possibly find. We were always interested in roots music. We loved jug bands, we loved jazz. Three of us grew up with strong Fats Waller influences at home from our parents. He was huge in Britain; our bass player’s father had his own trio playing Fats Waller numbers.

We were white suburban intellectual kids. We thought about art and our concept. We used to do interviews in bizarre ways. We’d bring an alarm clock and we’d only answer questions with quotations from famous people, that sort of thing. We felt we really had to revive the British music tradition. No one had done it. We thought the traditional music of Britain should be the popular music of Britain. Our popular music had been imported since before the jazz age. So we were trying to play to the mainstream, to turn it into popular music. We always thought it was going to be chart stuff, a big thing, but it never was.

MJ: Was there interest in British traditional music prior to what Fairport was doing?

RT: It was invisible from the mainstream of music. There was a folk revival around ’58, ’59, with people like Ewan MacColl and Burt Lloyd. But they were basically rescuing traditional folk music and finding the last of a generation of those singers.

After the folk revival in the late ’50s, a lot of folk clubs sprung up, hundreds. And people started to play what was probably called folk music. In some cases this was traditional music, in some cases just acoustic music. You had people like Martin Carthy, Davey Graham, Shirley Collins, the Watersons, and some of the people who Burt Lloyd and Ewan MacColl had already found.

MJ: What is it about British music that you connect to?

RT: It’s older. Some of what you hear in American folk music, a song like “Black Jack Davey,” goes back to Scotland in the 1600s. When you sing a traditional song, you feel the history behind it. It’s an extraordinary thing. You feel this reverberation down the corridors of history. Once you feel that, you get addicted to it, nothing else seems the same. These are some of the best songs you could ever hear, in the sense that these songs have been polished and honed by successive singers. The verses that don’t advance the plot have been erased.

You have these extraordinary songs from a time when sitting around and singing in a pub would be an evening’s entertainment. It was the news: A ballad would be telling you about a battle, or the incestuous goings on of the aristocrats up the road. There are songs of people getting carried away by the fairies, songs of social injustice, and, of course, simple, beautiful love songs.

MJ: The songs on I Want to See the Bright Lights Tonight are all based on imagined characters. What was going on with the songwriting at that time?

RT: I was really immersing myself in field recordings, the real raw stuff. So a lot of it comes from that. And a lot of that kind of weird stuff is in folk music anyway. I was just kind of recycling the weirdness of it. But again, that’s an album that’s trying to bridge that gap between traditional and popular. It’s a fun record. We made that in three days. It cost £2,500 ($3,910) to produce.

MJ: What’s the story behind the Henry the Human Fly album cover? It’s quite a weird one.

RT: It’s kind of a train smash, you know—it’s just a mess, really. The then-art designer at Island Records—this was sort of in the hippie era—I’m not sure how well qualified she was to be anything of the sort. I said I want to call the record Harry the Human Fly. She says, “Okay, I’ll get you this fly costume, we’ll go out to this house in Cambridgeshire.” You could rent the house very cheap. It was basically this bankrupt aristocratic family’s house, still full of stuff. But the fly costume was woefully inadequate; I had expected something a bit grander. It’s just a headpiece and a couple of flimsy wings she made, utterly hopeless.

MJ: How did Jeff Tweedy approach producing your new album?

RT: He kind of accepted the songs pretty much as they were. We tweaked a few things; we’d leave out verses, change the rhythm here and there, add harmonies where none were originally intended. He did some keyboard overdubs and guitar overdubs that I thought worked really well. But we basically just tried to record live as much as possible. It’s a fully naturalistic approach where what’s performed is pretty much what you get, sonically. There’s no big tweaking going on. I think Jeff’s a very sympathetic producer because he cares about the artists being the center of their own music.

MJ: You’ve created your own musical language as a guitarist. How did that develop?

RT: I play in slightly different modes and scales. Some things overlap, pentatonic scales that you associate with the blues also work for some English or Scottish music. Some of the bent notes are different as well. There’s a lot of bending up, from the root up to the second, rather than from the seventh up to the root. I try to avoid blues guitar clichés. Inevitably there are some, because it’s a guitar and you’re bending notes and that’s what happens, but I do try to think differently about it.

Musical vocabulary is very important. I still feel I’m trying to establish a vocabulary that sits into that world between traditional and popular again. I’m still trying to do now what I was trying to do in the 1960s.

MJ: Having recorded steadily over a long career, what helps you keep going?

RT: You have to be interested in the song as an idea. You have to keep your ears open. You have to be ready when something comes along and grab it and not say, “Oh I’ll remember that later,” because you won’t. Write it down and use it. If you’re going to write a lot of songs, you have to think about repeating yourself and how to avoid that if possible. I’m looking for different subjects, different ways to write that love song. Different angles all the time.

MJ: In the ’70s you became involved in Sufism, even appearing on an album cover in religious dress. Is that spirituality still in your life?

RT: Yes. I’ve been a spiritual person since I was a kid. I think when I was 15 I picked up a book in the bookshop about Zen. I started reading and thought, “Oh that’s fascinating.” There was a great bookshop in London that carried books about esoteric religions and philosophy called Stuart and Watkins. It was up a little alley, very Harry Potter. I read my way through the whole thing and took my preferences from there.

MJ: How does that relate to your music?

RT: Music is very spiritual stuff. No question. Kurt Vonnegut had said, “Should I ever die, God forbid, I want my epitaph to read: ‘The only proof he needed for the existence of God was music.'” I feel the same. Music is the thing that can lift you beyond this world in extraordinary ways. Nobody quite knows how this happens, but it’s extraordinarily powerful stuff.

MJ: You’ve described yourself as very shy when you were younger. How do you think shyness affects creative people?

RT: It’s a funny thing. I can never tell who’s shy and who isn’t. Danny Thompson, a bass player I’ve worked with, will say, “I’m really quite a shy person.” What? He’s always the loudest person in the room!

A lot of shy people end up on stage. Being on stage has done me a lot of good. It took me a long time—I used to kind of hide in the back. Even though you’re shy, there’s this thing in you that wants to get up there. I remember being six years old and getting up at a party and singing something. This is me, a kid with a bad stutter, but somehow I get up on stage and do this.