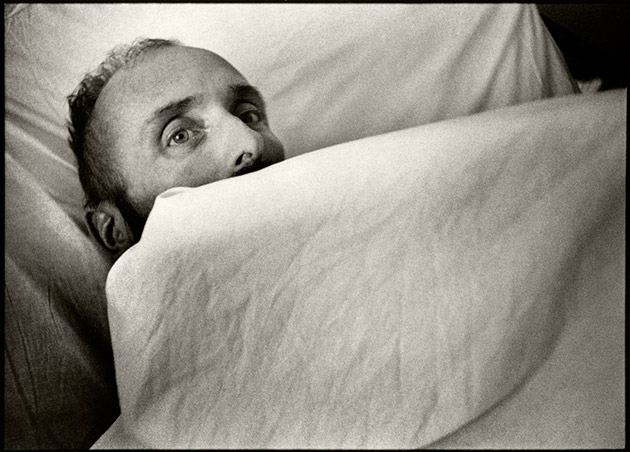

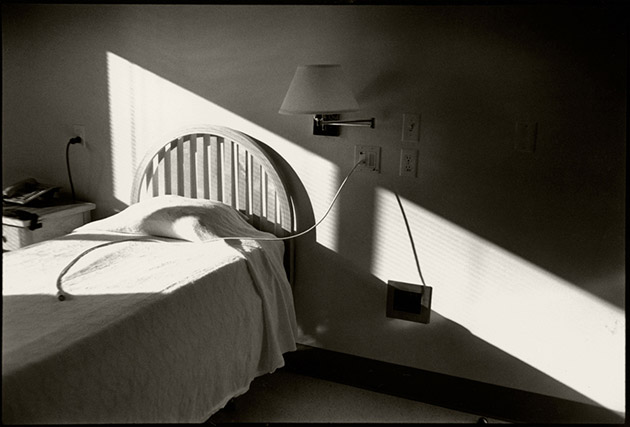

Light filtered in through shaded windows, casting shadows over Larry Hawkins’ bed. His room was often kept dark. In the final throes of his battle with AIDS, he was sensitive to brightness. There was just enough light for photographers Saul Bromberger and Sandy Hoover to take his portrait. It would be one of many they took to capture the devastation of the AIDS epidemic and the resilience of its victims.

The year was 1992. Ten years had passed since AIDS had been officially named and defined by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. It was the year the virus became the No. 1 cause of death for men ages 25 to 44. It was the year the international AIDS conference had to be moved out of the United States due to federal travel restrictions. And, it was the year that Bailey-Boushay House opened its doors in Seattle as the first nursing care residence and day health program for HIV/AIDS victims in America. Larry Hawkins was one of its first residents.

Saul speaks slowly over the phone as he walks me through thumbnails of the photos he shot more than 20 years ago. He pauses to reflect on particular photos, remembering the moments he and Sandy, now his wife, shared with residents. For many, those were the final days of their lives.

Saul and Sandy had initially been commissioned by Virginia Mason Medical Center to document the opening week of the Bailey-Boushay House, to help ease the stigma associated with HIV and AIDS. As they began to connect with residents, family members, and staff, Saul and Sandy decided they couldn’t stop after just a week.

“When we walk into this place back in ’92 we are surrounded by commitment, by the staff, by families, by a great deal of volunteers,” Saul reminisces. “We took it upon ourselves to give them a voice. To show someone looking in from the outside, ‘This could be me.'”

For the next three years the photographers would visit the house a few times each week, going room to room. Sometimes they wouldn’t even take photos, just sit and listen to the stories. “We became, in a way, not just photographers,” Saul says, “but part of the community in the house.”

Larry was one of the first they spoke to. Beloved among the staff, he was a gay man who had been a social worker before he contracted the virus. “I was a good one,” Saul recorded Larry saying of the work he did helping drug addicts in Seattle. “I just always liked people and wanted to help them out.”

It was a difficult blow when Larry succumbed to the illness. Though it was something the community had to face often, Saul said the uncertainty made it even more difficult. “They may have a day. They may have a week. They may have a couple months—you just didn’t know.”

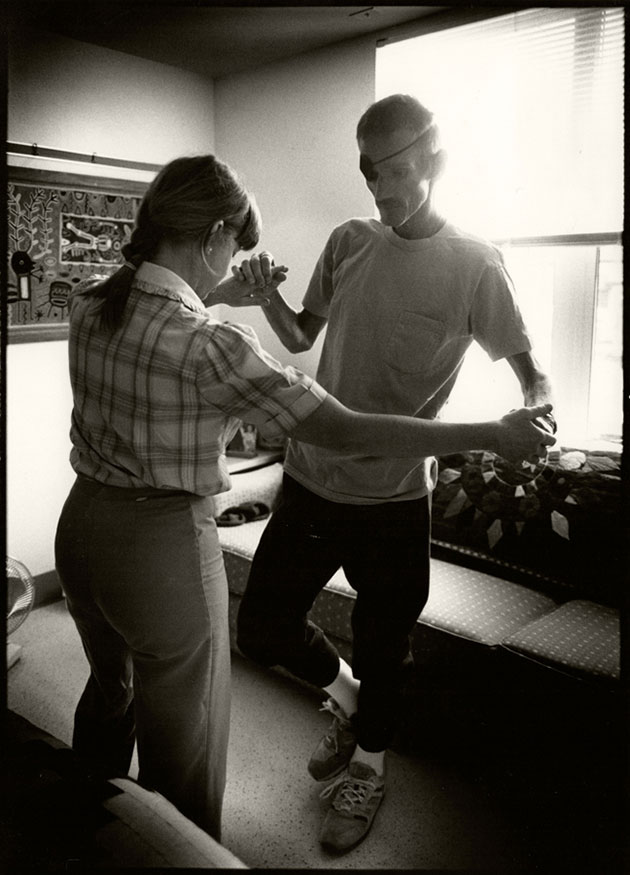

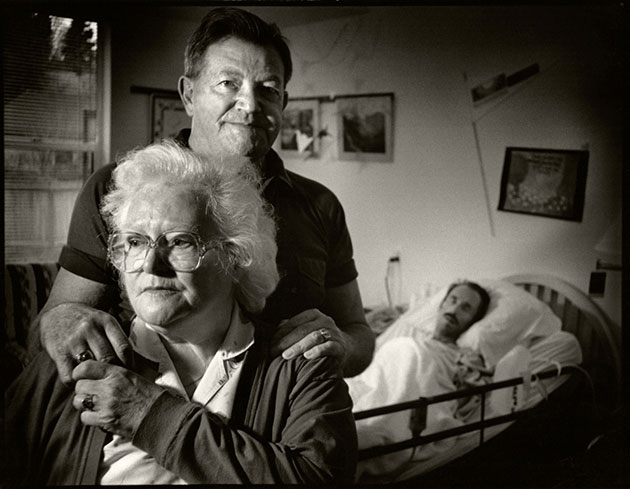

At times it became almost too much for Saul to handle. He described Joel, who was often visited by his mother, Ida. During one shoot with the two of them: “All of the sudden she starts bawling. She is crying uncontrollably. What she is saying over and over again is ‘I should be the one who goes first. I should be the one. It should, not be my son.'” Saul struggled to take the portrait and Sandy had to take over.

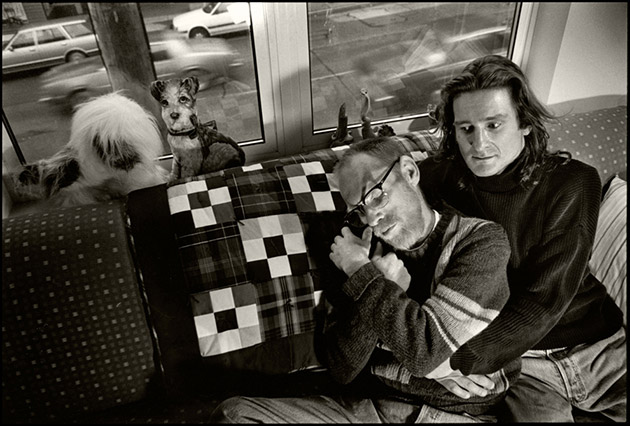

Then there was the chef of the house, who posed for a photo with his partner. By the time the photographers next returned, his partner was already gone. Saul took a picture of his made bed, bathed in sunlight instead. “That has become one of the iconic photos in the project. You can talk a lot about spirituality and metaphorical things and what they really mean. But this was a very spiritual moment here.”

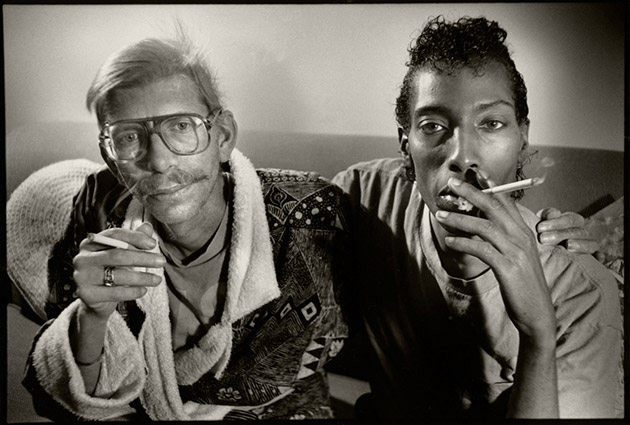

Despite all the loss and trauma, the project shows a community that celebrated life. Weekends were filled with joyful visits with family. There were birthday parties and new friends who met to smoke together outside in the sunlight. There was a strength and a resilience that surprised even Saul and he says that was what he and Sandy wanted to reflect.

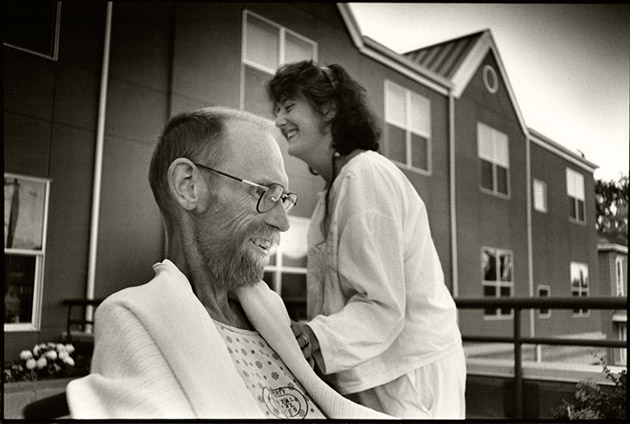

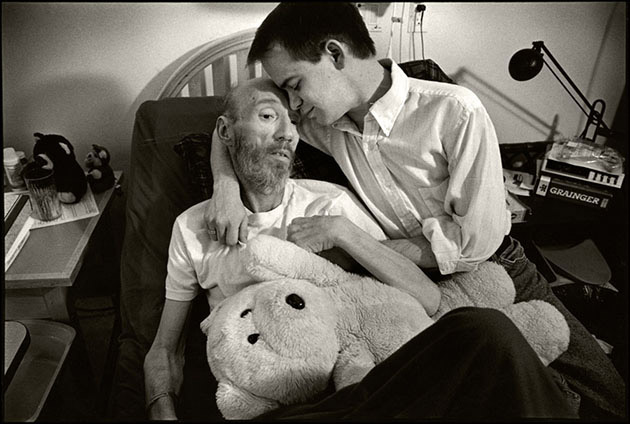

Sometimes they chose not to document the harsher realities of the disease, focusing instead on the sentiments people wanted left behind. Bill Blackmar agreed to have his legs photographed to show how the skin was peeling away. Instead the portrait captured a moment when he is being held by his partner Jimmy.

On Bill’s lap is a teddy bear, one of 12 he called his “burial bears.” Each had a name and Bill had asked that his ashes be placed in each one to be given to his family and friends after he passed away. “When I’m gone,” Saul remembers him saying, “they’re still going to have me.”

In 1988, December 1 became internationally recognized as World AIDS Day, and we have come a long way since then. New drugs and therapies greatly increased the life expectancy for those living with the disease and more effective prevention measures have reduced the rates of transmission. Still, a vaccine does not exist and there is no cure for the illness that has claimed nearly 39 million lives. There are 35 million people currently living with HIV/AIDS around the world and the number continues to grow. Saul says he hopes his photos give victims a voice and ensure that the stories of the past are not forgotten.

“That is one of the challenges of any documentary or photographer or storyteller,” Saul says with a pause. “It is to tell a story that is so hard to read or to look at, but still get people to look.”