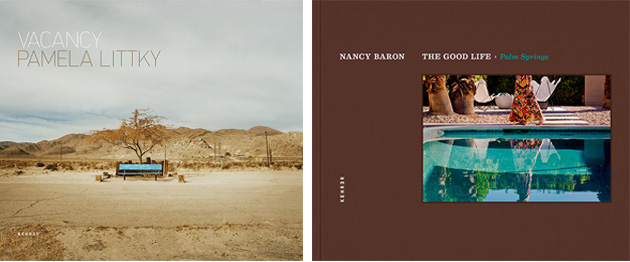

Three recent photo books offer very different perspectives on life in the American desert. Vacancy: The Gateway to Death Valley (Kehrer), by Pamela Littky, documents scenes in Beatty, Nevada, and Baker, California. In The Good Life: Palm Springs (Kehrer) Nancy Baron delivers on its title, giving a taste of the upper-crust desert lifestyle.

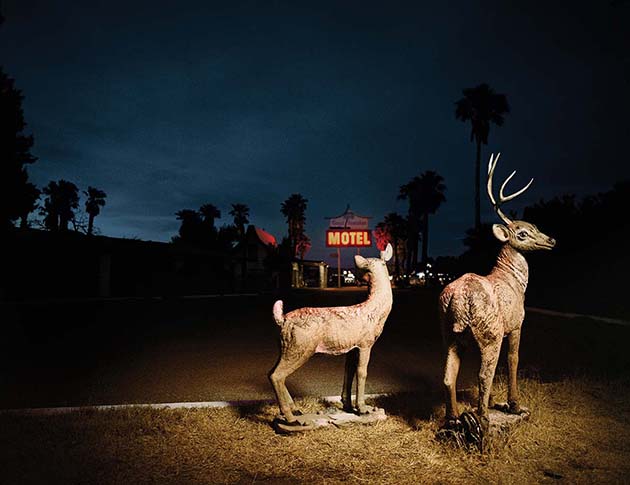

Vacancy–a little shabby and weathered, yet resilient—represents what some would consider real life. It’s an honest look at two hardscrabble desert towns separated by Death Valley. Vacancy isn’t without it’s oddly still moments. Even the portraits carry a hint of Errol Morris’ 1981 documentary Vernon, Florida–everyday people captured plainly in their environment. A little too real, maybe. In addition to the portraits, Littky takes us out around town, showing a burnt out trailer, a lonely country store, deer statues, trailers, and empty pools.

Tony and Sam at the Atomic Inn (Beatty, Nevada) From Vacancy by Pamela Littky

Pool at Wills Fargo Motel (Baker, California) From Vacancy by Pamela Littky

Lawn Deer, Baker (California) From Vacancy by Pamela Littky

Sharon and Arie (Beatty, Nevada) From Vacancy by Pamela Littky

Burned Out Truck (Baker, California) From Vacancy by Pamela Littky

Country Store (Baker, California) From Vacancy by Pamela Littky

Bingo (Beatty, Nevada) From Vacancy by Pamela Littky

Liquor Snacks Soda (Baker, California) From Vacancy by Pamela Littky

The communities Littky shoots fulfill our stereotypes of salt-of-the-earth desert living—unless the first thing you think of when you hear “desert life” is Palm Springs. While her pools might contain just a couple of feet of dark, murky water, those in The Good Life, Palm Springs are blue gems surrounded by sparkling white concrete. Everything is in place—perfect in a showroom kind of way. The desert without the dust. Some people have strong feelings about Palm Springs, seeing it as a veneer of life, at best, or as a sort of utopia. The Good Life shows us the idealized, almost stage-crafted lifestyle that has come to epitomize Palm Springs.

Bob’s Red Car From The Good Life: Palm Springs by Nancy Baron

Pink Shoes From The Good Life: Palm Springs by Nancy Baron

Mike and Bob From The Good Life: Palm Springs by Nancy Baron

Blue Wall From The Good Life: Palm Springs by Nancy Baron

Mighty Joe From The Good Life: Palm Springs by Nancy Baron

Golf Course Plane From The Good Life: Palm Springs by Nancy Baron

Depending on where you come from you’re likely to favor one of these books over the other. Or at least one is least more likely to evoke The Twilight Zone.

Beyond their subjects, the look of the two books provides a notable contrast. Vacancy carries more brown and yellow tones, with almost a dusty, desaturated look. The Good Life pops with blues and greens and a bit of pink. Another small but important difference is the use of tighter shots in The Good Life. You get less exterior mess, less serendipity, more claustrophobia, and ultimately a sense of formality, of everything being in place. In Vacancy, the shots are medium to wide, which adds a feeling of openness but everything is also less tidy, probably a lot like life in Beatty and Baker.

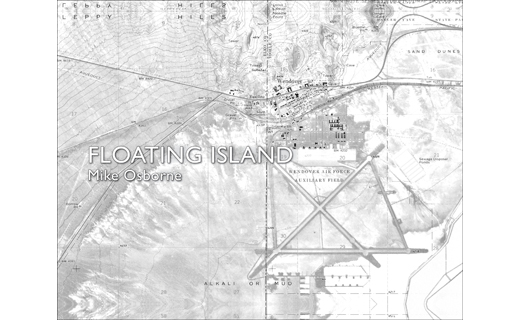

As an addendum, I should mention Mike Osborne’s excellent Floating Island (Daylight), which documents life around Wendover, Utah, and West Wendover, Nevada—a military base-turned-casino destination that straddles the state line a few miles from the Bonneville Salt Flats. The Enola Gay pilots trained in Wendover. Of these three books on the desert, Osborne’s is the smartest. He shot each of his 13 chapters with a very unique feel, based on the focus, give each of them a distinct point of view. His landscapes look otherworldly, more than they already do. Casinos feel like funhouses, more than they already do. Surveys of the towns and their people have a more plaintive, direct approach. It’s easy to see how much thought went into the book’s conceptualization, shooting, editing, and design.

If you want a good, rounded look at life in the American desert, you should look through all three books. The only thing that’s missing, really, is the area’s very active military presence. If there hasn’t been a photo project on that yet, there’s a good book there as well.