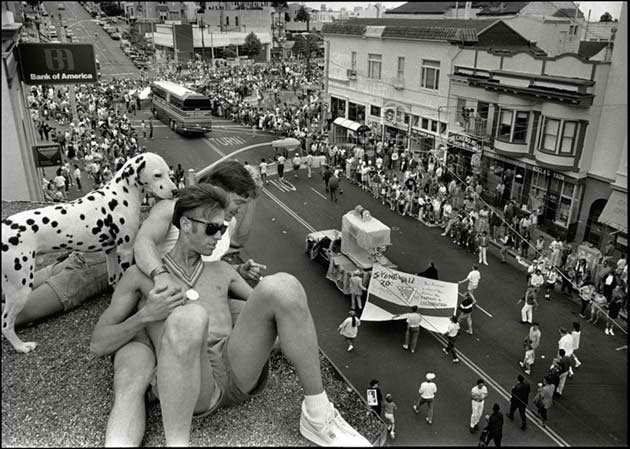

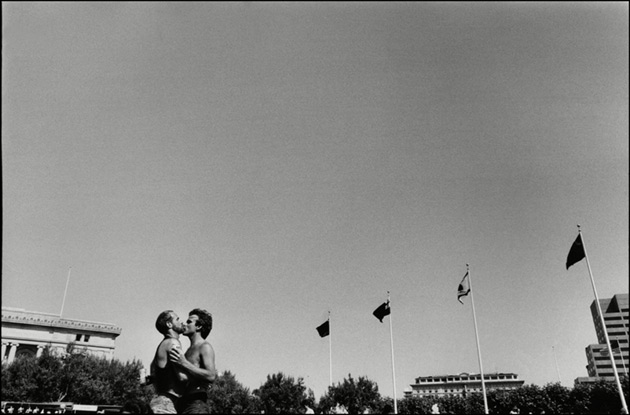

San Francisco Pride Parade, 1987<a href="http://www.saul-sandraphoto.com/">Saul Bromberger and Sandra Hoover</a>

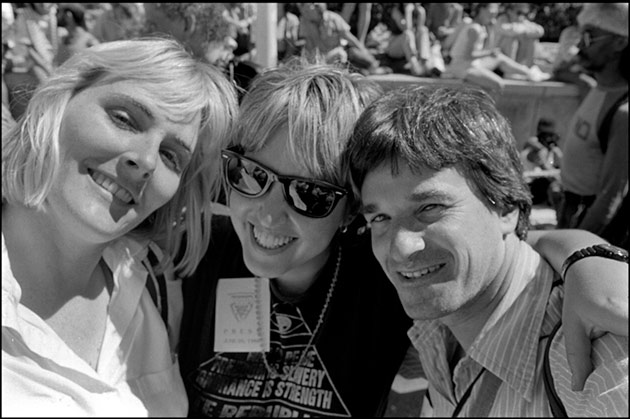

I can’t remember exactly how we all ended up going to Gay Pride brunch together at my friend Marta’s house that Sunday morning, in June of 1988. In retrospect, it seems inevitable that I would bring along Saul Bromberger, a photographer at the East Bay newspaper where I was a reporter, and his then girlfriend and now wife, Sandra Hoover.

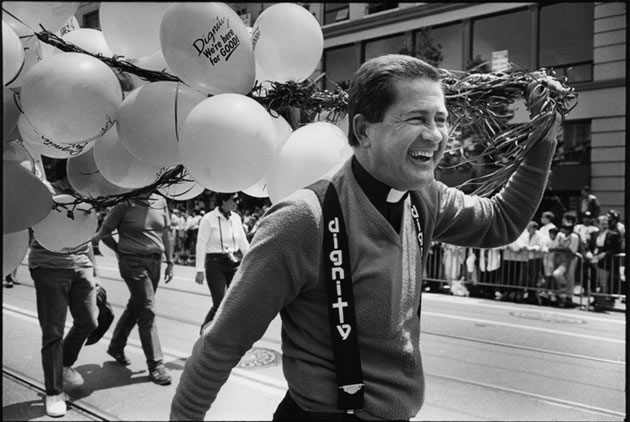

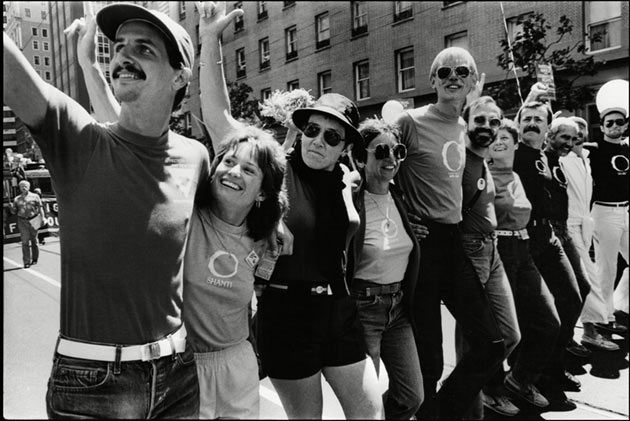

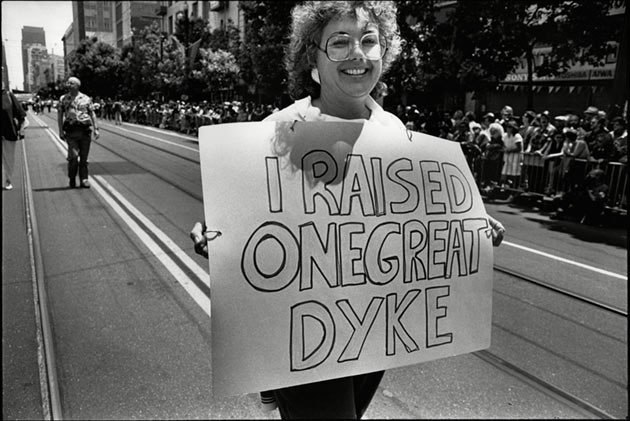

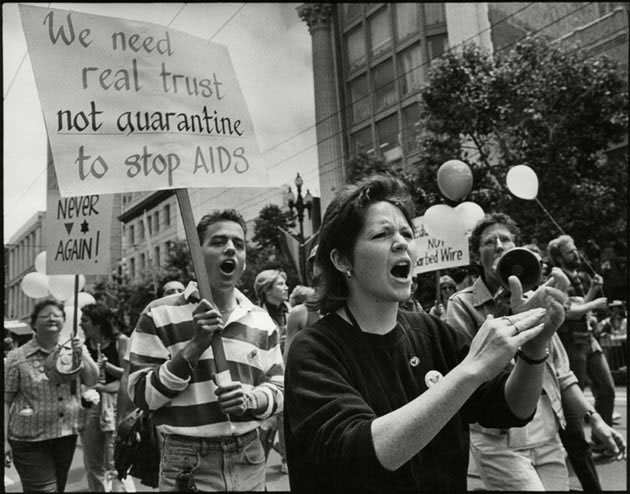

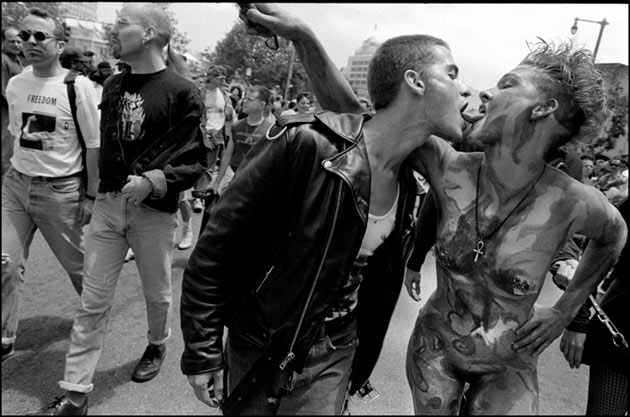

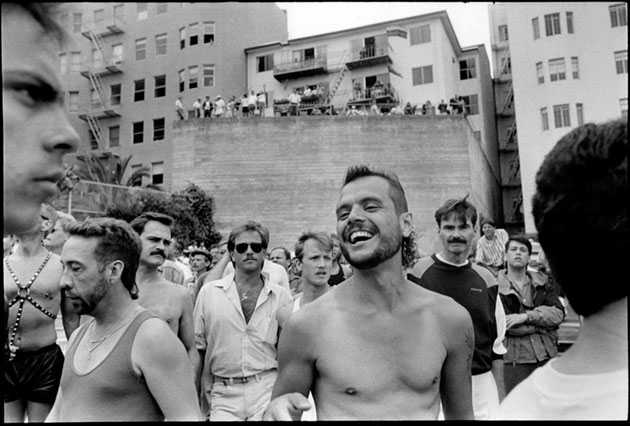

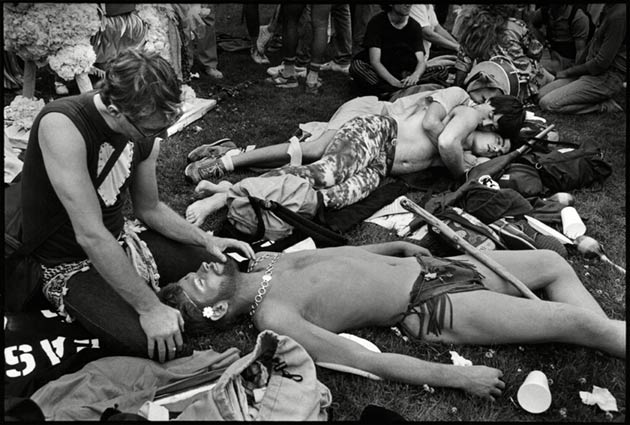

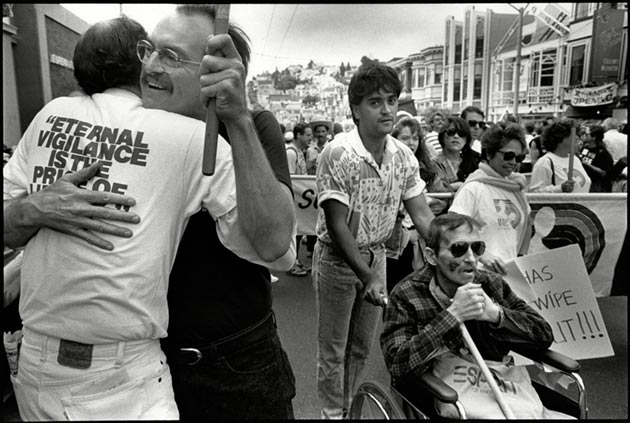

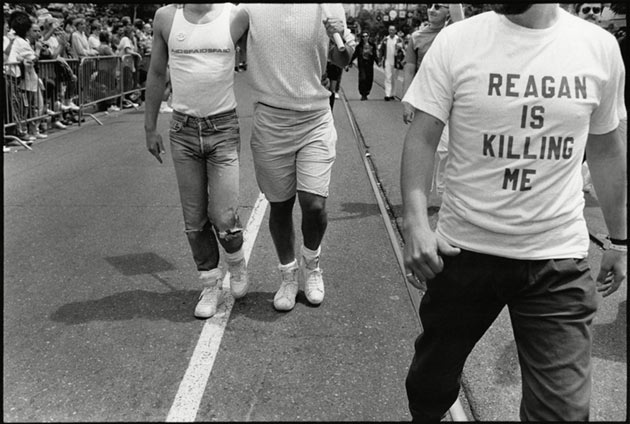

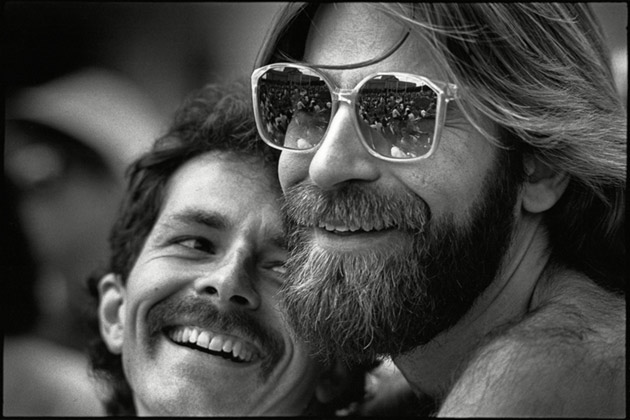

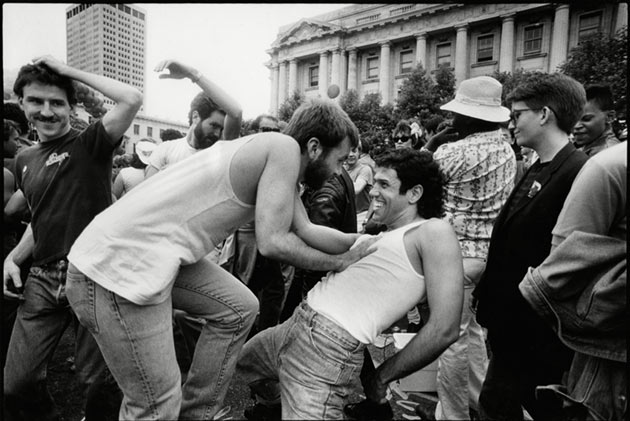

At the time, Saul and Sandy were already four years into a project that would last until 1990: documenting the San Francisco gay pride parade. It was the height of the AIDS epidemic, and anger at the world’s indifference to the disease was growing, generating radical groups like ACT Up (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power). So Saul and Sandy came to our pride brunch with cameras in hand.

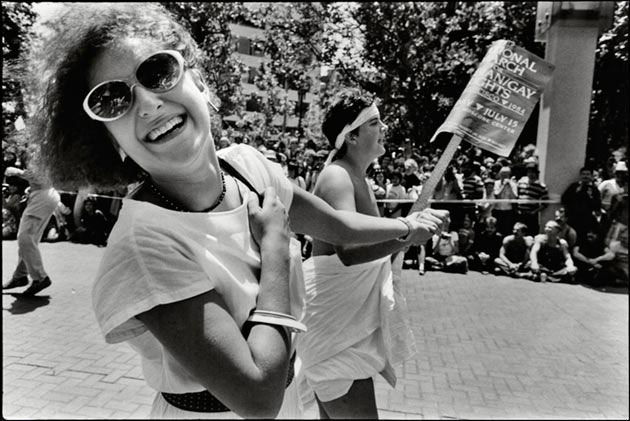

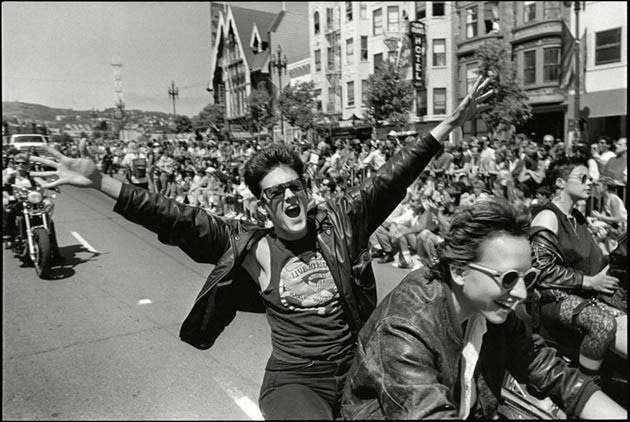

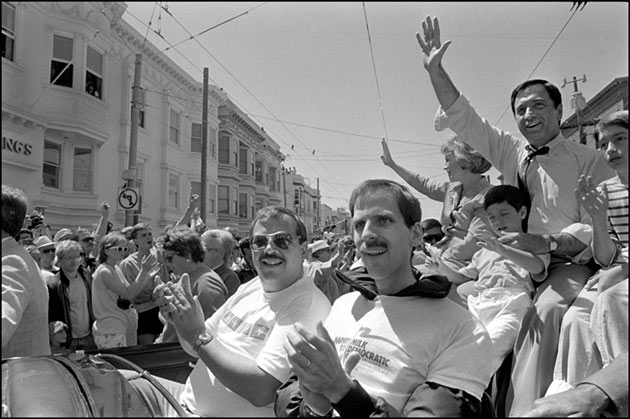

The pair started shooting the parades in 1984 because they believed they were witnessing history. “It was this kind of test I was giving myself: Can we document this movement that is also a parade?” Saul remembers. Unlike other photographers, he didn’t “just see people jumping around and dancing,” he says. He saw people “demanding change.”

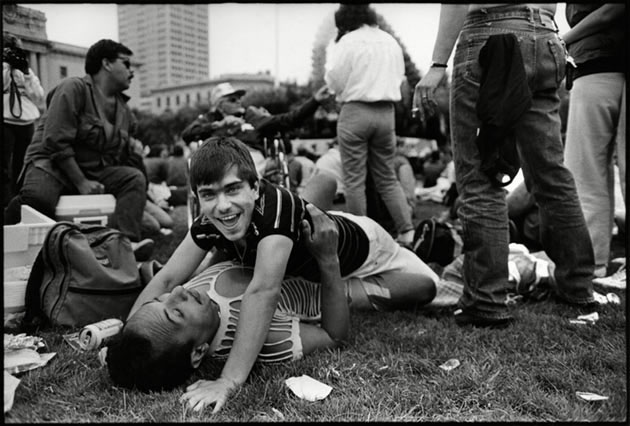

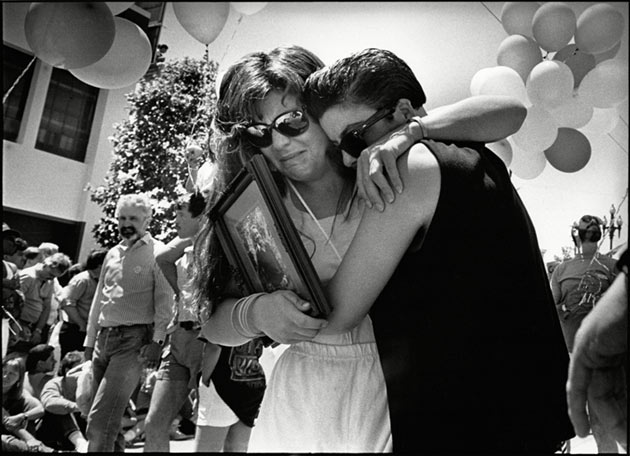

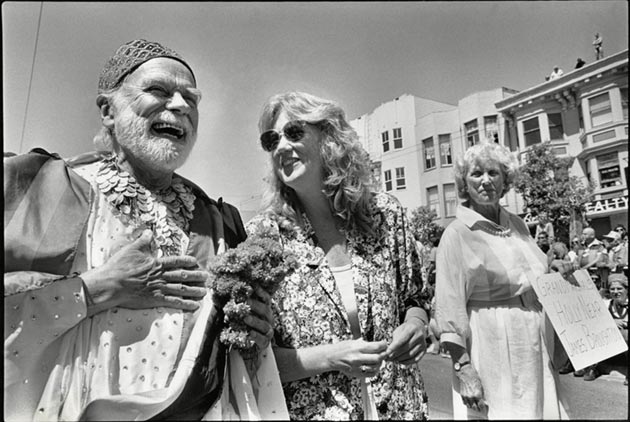

Saul and Sandy wanted to capture the celebration, the love, and the rage, and in so doing, to capture the heart of a movement.

They purposely eschewed the long lenses favored by newspaper journalists, who seemed focused only on the spectacle. Instead, they got close to their subjects. They talked to them. They made friends. And the pictures they took were intimate and close.

But when Saul and Sandy asked to shoot the brunch (or maybe—I can’t remember to be honest—I invited them) they were putting me in a place I hated and loved at the same time.

A heads up: Some of these photos contain nudity.

This was a time when the gay world often existed separately from the straight one, and before cameras were everywhere. They needed permission to be there. We trusted them.

I also knew they had to be there. I wanted them there. I felt honored. But I also felt scared and exposed. My experience back in 1987 was that if you didn’t purposefully and repeatedly out yourself, you were not out. There was no social media where you could simply declare yourself to be something other than straight and then watch the consequences unfold.

You had to tell people over and over again. You had to make yourself the story.

It seemed easier not to do it. Besides, I was a journalist, an outsider. I covered the stories. I didn’t make them. Like Saul and Sandy, I’m an observer by nature.

It felt strange to thrust myself into the spotlight. I could alienate people. What if my sources stopped talking to me? It wasn’t just an idle concern. It happened. But it was more than that: Like most humans, I didn’t want to put myself in a box. I didn’t want to be other.

Just a few years before, in my early 20s, I had concluded that something inside of me was broken. I had great boyfriends. I just couldn’t fall in love. I had resigned myself to a life without love, when on a balmy night in my senior year of college, my female roommate and I stepped out onto the sidewalk and fell into a passionate kiss. Yes, I kissed a girl and I didn’t just like it. It rocked my world. I got it. And in that moment, I realized I was not broken. I was just different.

It was an intensely personal, intensely private discovery. But I quickly understood that if I were to date people of my own gender, I would be taking a political stand, like it or not. I couldn’t remain a detached observer.

So when I went to the pride parade, it wasn’t just to party. I went because, like so many others, I needed it.

I needed to fuel up on all the pride, all the love, all the righteous anger, all the togetherness. It was an infusion on which I could draw during the year. When someone yelled “dyke” at me and my girlfriend in the street, or a friend suddenly shunned me, or a relative told me that they didn’t understand but still loved me even if I was wrong, I could tap into that reserve.

Recently, I was talking with Saul about those years. He seemed miffed at himself for not putting his work out there: Every year they’d go to the parade, take amazing photos, and develop them. They’d hand out these beautiful prints to their subjects. They’ve always been generous like that. My halls were lined with them.

But then they’d go in a box under the bed.

“There were a lot of pictures I took back then that I never submitted to the paper because I thought they were personal,” Saul says.

Surely they could have gotten them out before. Surely, they would have gained notoriety for capturing a movement in advance of everybody else. I’ve been thinking about that: Why didn’t they bring these pictures out?

I think I know. I think in a way they kept them in a box for us. To protect the community from a world that could be hostile and cruel.

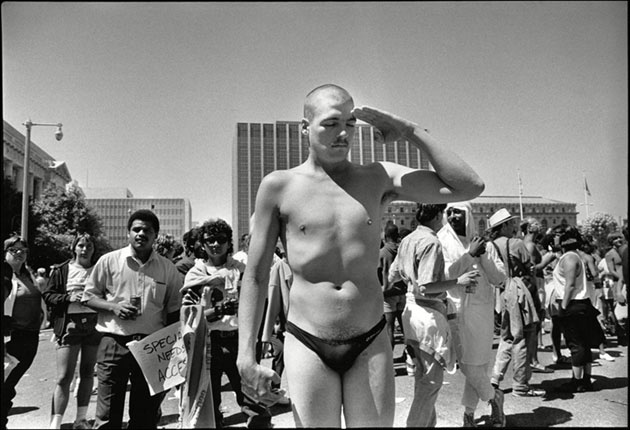

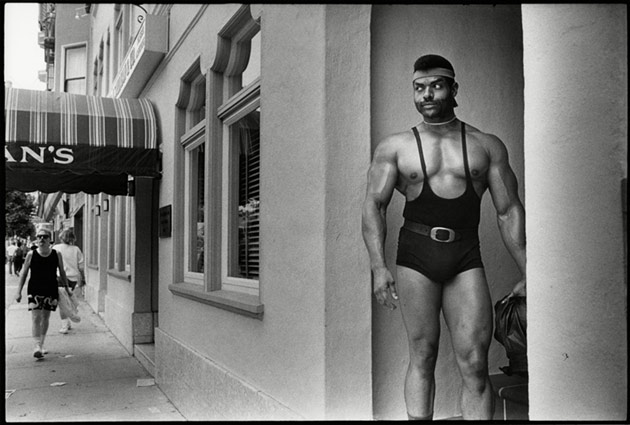

These pictures show something soft and vulnerable. They show humanity. But they also show nudity. It would be easy to take them out of context.

And to bring them out into the glare of society where they could be ridiculed—maybe they didn’t belong there. Not yet.

When we recount history, inevitably we reshape it, sharpening memories with new revelations and forgetting other parts altogether.

But these pictures capture unflinching, static moments of a different time. There’s a picture of a bare-breasted woman carrying a whip. There’s a picture of a couple on a roof with their trusty dog. There’s a picture of five men in a window, three of whom I know for sure died of AIDS.

The past lives and breathes in these photos. And it’s important to remember history. It’s important to see ourselves from a distance, especially when the closet walls have fallen and here we are.

For more of Saul and Sandy’s SF pride pictures go to their site: PRIDE – The San Francisco Gay & Lesbian Freedom Day Parade: 1984 – 1990.