Rodney Crowell is a master craftsman of the song. Arriving in Nashville in 1972, his early years were spent in the close orbit with fellow luminaries Guy Clark and Townes Van Zandt. He also found a productive relationship with Emmylou Harris, writing many songs that she recorded, and joining her elite Hot Band as rhythm guitarist. While married to Roseanne Cash he produced her landmark album King’s Record Shop. Not long after, he had his own breakout album, Diamonds and Dirt, which launched five No. 1 Billboard country singles.

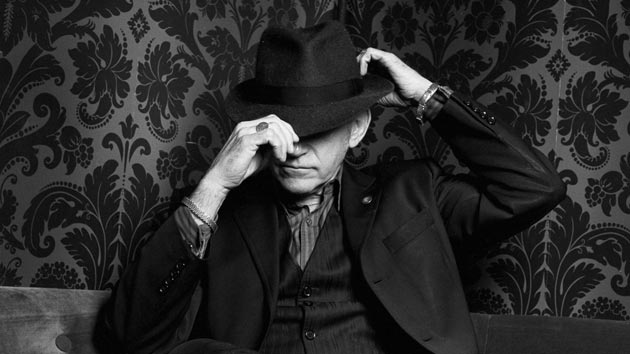

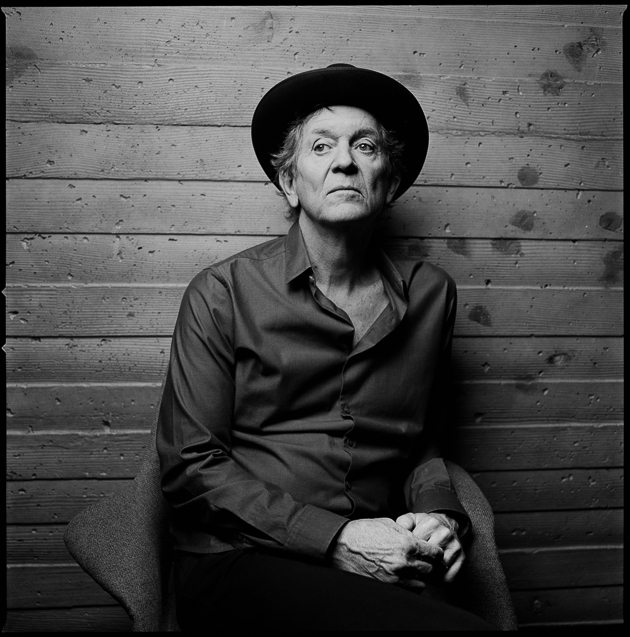

After the hot streak cooled, Crowell continued to whittle his songwriting to a fine point, mining his experience and inspirations for more personal yet universally resonant works. Following last year’s Grammy-winning collaboration with Emmylou Harris, Old Yellow Moon, he released his latest—15th!—solo album, Tarpaper Sky. Photographer Jacob Blickenstaff spoke with him recently in New York City. The following is in Crowell’s words.

I never focused on writing songs for others. That doesn’t work, and in fact I can’t do it. All of the success I’ve had with other people performing my songs was a result of just writing “for the sake of the song,” to quote Townes Van Zandt. I learned early, when I got involved with Emmylou Harris recording my songs back in the 70’s. I spent a day writing a song for her, took it over and played it for her, and she says, “That’s real nice, but I heard this demo of this song you wrote and I want to record that.” It hit me that you just have to write the songs for the song. People will cover it.

I do primarily consider myself a songwriter. I’ve always been in the business of tracking down songs, finding their trail and coaxing them out of hiding. I also hold to the theory that once it’s written, it’s got to be performed. Writing is a performance art, I think, and once the voice delivers it, it completes the circle.

I’ve made a study of inspiration based on my own experience. The kind of inspiration that came to me as a young man in my twenties was broad strokes: the theme of love or the theme of the landscape in Louisiana, the theme of running from the cops or the theme of a vacation that I couldn’t afford because I’m a poor boy from Houston. It was broad-stroke by nature, because when creativity is starting to flower it first opens up on a more broad scale. As time moved on, I could get more involved in my own experiences and become more singular. People say to me now, “God, I love what you’re writing, but it’s so you, I can’t record it,” and I understand that. That’s part of the ongoing process of how do I keep the craft sharp enough that occasionally the inspiration finds me worthy of visitation.

I’ve complained about the digital age, but with iTunes I’ve been able to do a study of old blues records and jazz from the ’20s. I always had a fascination with Lightnin’ Hopkins. I really do have a love of acoustic blues from Robert Johnson to R.L. Burnside, and Son House. In a way, Howlin’ Wolf is in that tradition and certainly Muddy Waters—part country blues, part Chicago blues.

To keep myself sharpened, I’ve been trying to understand how would I express the blues. I’m not Lightnin’ Hopkins, and if I attempted to perform like him I’d sound like a blue-eyed white boy. But there is a blues man inside me, and I’m looking for him. I have been tapping into those songs and writing from that perspective. I can follow the blues back to where I find myself in it.

Since I wrote Chinaberry Sidewalks, I got a lot more of the sense that I have to develop my self-editor, which makes my process slower because I spend more time with the songs. I revise songs two or three times to refine the the language. I hear songs that I’ve written in 1972 where I think I let a lot slide by.

Emmylou and I have written seven songs together this year. We’re thinking about making a second album together. I found that it was a bit of a relief; I had gotten so far into self-editing and really making sure I got a jeweler’s-eye view of what I was trying to say, and Emmylou was very sweetly going, “Hey, we were good three revisions back.” Emmy gave me ease in the process.

I like the satisfaction of the creative conversation. Mary Carr, a very gifted poet, writer and memoirist, I collaborated with on Kin. She had worked singularly as a poet and a writer of prose and when she got involved in the collaborative process you could tell she was intoxicated by it. She was part of our creative process in the studio. People who spend time alone in front of the typewriter or the computer screen don’t get to experience the beauty of that collaborative conversation that goes on between musicians. The self-consciousness is gone. I always say that self-consciousness is the enemy of good art.

I don’t find songwriting to get any easier. You get older, time flies by, and I believe that inspiration only comes to an artist of certain years if the dedication and the passion are still there. Going out on the road and getting around will kind of daunt your passion a bit, but not enough to back off. Before I leave this world, if I can create something that’s timeless and museum quality, then it will have all been worth it. And if I don’t? It would have still all been worth it.

“Contact” is series of portraits and conversations with musicians by Jacob Blickenstaff.