BuyEnlarge/Zuma

During last week’s State of the Union address, President Obama offered the usual bromides about giving every citizen a fair shake. “Here in America,” he said, “our success should not depend on accident of birth, but the strength of our work ethic and the scope of our dreams….It’s how the son of a barkeep is the Speaker of the House, how the son of a single mom can be president of the greatest nation on Earth.”

Few goals earn more rhetorical points in DC than defending America’s status as the land of upward mobility. In his public speeches, President Obama has begun using equality of opportunity language as a replacement for “income inequality,” a term more freighted with class conflict. But maybe that’s not such a good idea. Gregory Clark, a Scottish-born economic historian at the University of California-Davis, argues that our identity as a nation of bootstrappers is largely a myth.

In The Son Also Rises, which publishes later this month, Clark argues that researchers have vastly underestimated how hard it has been—and how hard it remains—for someone born into a low-status situation to ascend the social ranks. His results come from tracking the historical incidence of surnames across generations of tax rolls, university enrollment logs, and professional society membership lists in various countries. I called Clark to talk about his findings and the new book, which veers into areas of academic inquiry that some readers may find a bit uncomfortable.

Mother Jones: How much of a consensus is there among economists that any American can go from rags to riches?

Gregory Clark: Conventional studies suggest that we live in highly mobile societies: Within two or three generations, your family history is really not going to matter.

MJ: And those findings have been used to justify a kind of callousness: Why bother helping people if anybody can be successful, so long as they try hard enough?

GC: Right.

MJ: But your results are at odds with that.

GC: What I find is that the actual underlying rates of social mobility are much smaller than all these studies find. There’s a very high correlation of status across generations. The data suggest that more than half your overall lifetime status is predictable at the point you are conceived. And that number is just as big in Sweden, and just as big in medieval England. We have not in modern high-income, public-education, open-access societies actually managed to increase the rate of social mobility above what it was in preindustrial society.

MJ: That’s an amazing finding. Explain how you came to it.

GC: We look, for example, at the rich people in the 1920s who had rare surnames—names like Guggenheim or Roosevelt—and just track the average status of those surnames 80 or 90 years later.

MJ: How do you measure status?

GC: I have a number of different measures for different societies. So for England, where we have some of the best data, we know everyone who went to Oxford and Cambridge from 1200 to the present. That tells us who the educational elite were in England over 800 years, and then we can ask, “What are the names that are showing up in that elite, and how persistent is their appearance in this elite?”

MJ: Why are your results so different than those of previous studies?

GC: The existing studies look at something like your income relative to your father’s income. But income is just one aspect of your social status. I know someone who lives in San Francisco who has an undergraduate degree from Northwestern and a graduate degree from Stanford Law School whose current income would be approximately zero, and has been for the last 10 years. He has devoted himself to the study of Buddhism and he mainly lives on the income of his partner. So measured in terms of income he would show up as exhibiting drastic downward mobility. But his true social status hasn’t changed in that way.

There’s a lot of froth and instability in measures like income, and there is a deeper underlying stability to people’s social status. Looking at not only income but also education, wealth, health, longevity, you actually find that these things are changing much more slowly. If you have a rich father and your income falls a lot, we can predict that your children will likely move back up the income ranks. People know this from their own families—they see much more stability in terms of social status than these studies would suggest.

MJ: You’ve found, surprisingly, that access to wealth and education is not all that important as a determinant of status. Will you offer an example?

GC: Take England in the 19th century, where the only two universities were Oxford and Cambridge. To get admitted, you typically went to an elite private grammar school and you also had to attend Church of England services. We find that there is a very strong persistence of elite families at the universities. In recent years, the universities have tried to become more meritocratic and more democratic: They admit students based on performance on national exams. They don’t give any privilege to the fact that your parents went there. And public financing for tuition is now available. But what we find is that elite families persist at Oxford and Cambridge at the same rate as they did in the 19th century. It hasn’t managed to change the rate of social mobility.

MJ: But why not? Is it simply that wealthy families can afford to train their children to score better on entrance exams?

GC: Some of that we contest, because we can look at what happens to children who are adopted into other families who often come from less elite backgrounds. What we find is that the adopting family can have some influence on the outcomes for these children, but the majority of the outcome is actually predicted from the family of their birth, and not the family they were adopted into.

MJ: So are you saying that genetics, not just culture, contribute to a person’s ultimate status?

GC: We know that both must play a role. I don’t have data that can clearly sort these two things, but the nature of the inheritance that we observe is always consistent with genetics being the major source of these advantages.

MJ: But if you followed that logic, wouldn’t it imply that certain ethnic groups are smarter or more capable than others?

GC: There is no evidence of any racial differences in average ability in any of the data that I have. If you look at ethnic groups who occur as doctors at more than average frequency within American society, they are mostly non-white—black Africans, black Haitians, Egyptian Copts, Iranian Muslims, Hindus, Chinese, Filipinos. The evidence is that any group can, under the right circumstances, become elite—or become an underclass group in a society.

MJ: You had some interesting examples about how these “elite” groups are created.

GC: In Muslim Egypt, the high-status community is the Copts, who are Christians. Once Egypt was invaded from Arabia, the Copts didn’t have to become Muslims, but if they remained Christians they had to pay a head tax. Essentially, all of the poor Christians preferred to convert and avoid the tax. The high-status Copts stayed and have remained high status to this day. Similarly, there’s good evidence that the modern Jewish population became a high-status group by 90 percent of the population converting to Christianity, with the converts being the lower end of the distribution.

MJ: Your book also discusses how Coptic and Jewish surnames are associated with high status in the United States.

GC: The American Medical Association has a record of about a million doctors. If your surname is Jewish, you are about six times as likely to be a medical doctor as the average person. But it turns out that the most elite group by that measure are the Egyptian Copts. They are something like 18 times more likely to be a doctor than the average American.

MJ: You’re courting controversy, especially when you turn to explaining the persistence of disadvantage among groups such as the Roma or black Americans. The Economist accuses your book of “trafficking in genetic determinism” by being too quick to write off the impacts of social reforms. The Civil Rights Act is only 50 years old, after all.

GC: But even when you look at a society like Sweden, which has undertaken many of these programs for many, many years, you find very little ability to actually change that rate of social mobility very much. In Sweden, however, the disadvantages from being in the bottom 10 percent of the social spectrum have been very significantly reduced compared to the United States.

MJ: If this is all true, it might lead to some interesting conclusions: Don’t worry about funding scholarships at Harvard because it won’t change social mobility very much. Instead, focus on social services and increasing the minimum wage.

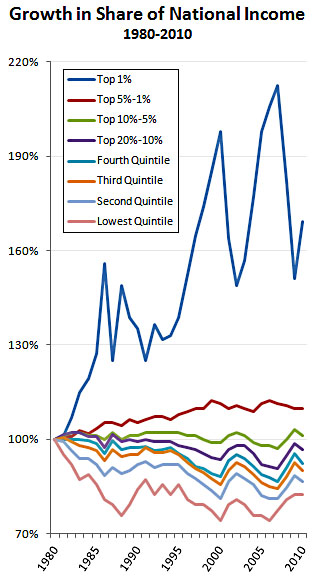

GC: I think it’s an argument for saying we should limit income inequality, because, also, we don’t think high wages are playing that much of an incentive role in determining what people do with their lives. Social status is just as persistent in Sweden—where there isn’t a huge income gain from being at the top of the ranking—as it is somewhere like the United States. So there is absolutely no reason to accept whatever the market spits out as the income distribution. We can decide what the income distribution should be.

MJ: That might be a hard sell in Washington.

GC: Look at it this way: I’m five-foot-seven. No one is going to believe that I have any possibility of making it in the NBA. But for some reason, in these other aspects of life we somehow think that everything should be possible for people. I think maybe it’s part of how we have to feel about the world in order to make our own way though it.

MJ: Of course, on an individual level, going from rags to riches is possible.

GC: Yes, and in the long run, everyone is the same. But it’s a long run. We find that 90 percent of the elites in a society are coming from people who are just slightly below that level. Very, very few are being drawn from families who fall way down the distribution. These transitions are good stuff for magazines and inspirational presidential speeches, but their frequency in real social life is quite, quite limited. The current differences in status will persist for hundreds of years. There will not be equality for Latinos and blacks within your lifetime or the lifetime of your children, your grandchildren, or your great grandchildren, if this data is correct. What’s happened in England is that the medieval elite are now finally average. But that process took 300 to 400 years.