Photos courtesy of Universal Pictures

Once upon a time a bunch of Brits got together to make a little film that Americans would bicker about for more than a decade.

Love Actually was released on November 7, 2003, and we have been arguing about it ever since. Some hate it, some love it; some love it when they’re in love but hate it when they’re out of love.

The traditional critique of the film goes something like this: “It is a saccharine soulless picture that relies on an emotionally manipulative soundtrack and has nothing to say but somehow takes 136 minutes to say it.” Variations of this critique may or may not include, “It is an evil film that tells people who are alone that they will never be happy.”

Yawn.

The Atlantic‘s Chris Orr is more bold: His latest entry into the anti-Love canon requires us to once again, verily and merrily, and with the full weight of history on our shoulders, rise in its defense.

Orr makes a lot of very good points, but his central contention that “Love Actually is the least romantic film ever” is simply insane. I know insane and that’s insane. (My insanity credentials? I have seen this movie probably 40 times.)

Orr writes, “Love Actually is exceptional in that it is not merely, like so many other entries in the [romantic comedy] genre, unromantic. Rather, it is emphatically, almost shockingly, anti-romantic.”

“Anti-romantic!” Here’s the thing: Love Actually is at its most basic level a call to romance. Not to love, necessarily, but to romance.

Also, all of you, everybody, stop comparing Love Actually to most other romantic comedies. Love Actually is only a traditional romantic comedy insofar as it is a film about romance that has humor. It does not have the structure required of the genre. To be honest, if you’re going to compare it to any one film you should probably compare it to Crash, the working title of which I’d like to think was Racism, Actually.

If the theme of Crash is “We’re all at least a little bit racist deep inside” the theme of Love Actually is “We’re all a little crazily romantic deep inside.”

Love Actually is, in fact, less a film about love as it is a film about people who think they are in love. Almost all of the stories center around people who either early on, or before the film even begins, figure out they’re nuts about someone and then spend the five weeks before Christmas wondering, “What do I do now?” It’s a bit like Hamlet but with romantic gestures instead of, you know, death.

Orr thinks it contains “at least three disturbing lessons about love”:

“First, that love is overwhelmingly a product of physical attraction and requires virtually no verbal communication or intellectual/emotional affinity of any kind. Second, that the principal barrier to consummating a relationship is mustering the nerve to say “I love you”–preferably with some grand gesture–and that once you manage that, you’re basically on the fast track to nuptial bliss. And third, that any actual obstacle to romantic fulfillment, however surmountable, is not worth the effort it would require to overcome.”

Let’s knock these out quick.

1) People fall in love based mostly on physical attraction

False. In Love Actually, as in life, people fall in love for crazy reasons.

Sam is a young boy who has recently lost his mother, Joanna. He informs his stepfather, Daniel, himself deep in mourning, that he has fallen in love with an American girl at school with whom he has not spoken. “She doesn’t even know my name. And even if she did, she’d despise me. She’s the coolest girl in school and everyone worships her because she’s heaven.” Orr attributes Sam’s attraction to the fact that the girl is pretty. I would venture that it might have something more to do with the fun coincidence that the American girl has the same name as the boy’s recently deceased mother…. “Her name is Joanna?” Daniel asks. “Yeah, I know. Just like mom. Spooky.” Spooky is one word for it!

The new Prime Minister, David, a confirmed bachelor, meets and subsequently falls for Natalie, an assistant at 10 Downing Street. He is immediately attracted and charmed by her. They flirt for a few weeks and then the President of the United States comes to town. He bullies the PM on all matters of diplomacy, resigning David to humiliation and weakness. Then the President makes moves on Natalie and it’s the last straw and David stands up for Great Britain in front of all the world and is met with adoring press from his constituents. This is a political triumph that will largely define his career and he will always associate it with Natalie. It might be because of a weird bit of psychology, but it is utterly and completely believable that he would at the very least think he was in love with her.

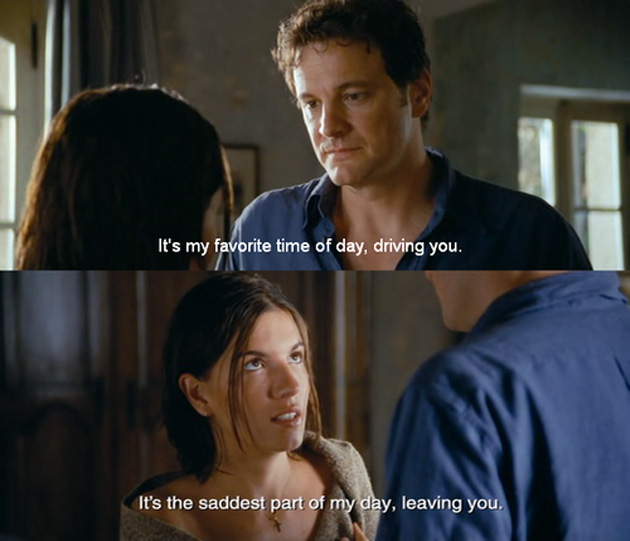

Jamie is a crime novelist who has recently had his heart broken. He has found that the person he loves was having an affair with his own brother. To wallow, he flees to France where he meets and falls in love with Auréalia, a Portugese housekeeper. Neither speaks the other’s native tongue and yet they both feel all the feelings. Orr looks at this and attributes those feelings solely to physical attraction. And it must be, the thinking goes, for they exchange not even a word until the third act! But the movie clearly translates her words as being exactly in response to his, even though they don’t speak the language, thus highlighting their uncanny soulmate-ness. This is the very concept of romance itself! They are literally made for each other and they know it.

So people fall in love for crazy reasons in the movie. But people fall in love for crazy reasons in life. This is truth.

2) “The principal barrier to consummating a relationship is mustering the nerve to say ‘I love you'”

“As soon as the characters in the film find the courage to say ‘I love you,’ their romantic journeys are essentially over and they go straight to the happily-ever-afters,” Orr writes. This is a tiny but important point: Only one character ever says the words “I love you.” It is Colin Firth in the film’s third scene. He says to his longtime girlfriend, “I love you…I love you even when you’re sick and look disgusting…Right did I mention that I love you?” “Yes, you did! Get out of here, loser,” she replies playfully. Moments later he finds out she is cheating on him with his own brother. The good romantic gestures that the film places such a great emphasis on amount more to “Hey, I have some romantic feelings for you. Do you maybe have some for me as well?” rather than to declarations of everlasting love.

And you know what? Mustering the courage to say “Hey, i have some feelings for you” is not some inconsequential thing. As anyone who’s ever been at the beginning of an affair knows, getting the nerve up to say “Want to take this further?” is a huge deal! It’s hard, it’s terrifying, and when it’s over, you either live to romance another day, or the relationship ends. That’s what Love Actually is about. Those terrifying moments before the proclamation. It isn’t about afterward, where reality lives. It’s about the beginning of the feeling of love.

But let’s circle back to the charge that Love Actually is “anti-romantic.”

Romance does not equal everlasting true love. Is the movie a meaningful blueprint on how to meet your life’s love and make it last with them forever? Of course not. But is it romantic? Yes! Romance is the big gesture. Romance is the love that erupts without a spoken word. Romance is skirting airport security.

3) “Any actual obstacle to romantic fulfillment, however surmountable, is not worth the effort it would require to overcome.”

Jamie learns Portuguese! Aurélia learns English and moves to England! The little kids are giving a long distance relationship a chance! Emma Thompson’s Karen—the film’s strongest character, who finds out that her husband has given a necklace to someone else and that same night confronts him about it; she does not hesitate; she does not trip over herself—is pretty clearly trying to make it work out with the film’s weakest character, her affair-of-the-heart-having-and-oh-so-close-to-adulterer husband (Alan Rickman) who has spent weeks upon weeks simply paralyzed by his temptation to have an affair, and who makes no decisions until they are forced upon him as though he had no volition at all! This is what surmounting looks like!

Orr goes on to point out that, as opposed to every romantic comedy ever, Love Actually dedicates no real time to showing the couples getting to know each other. This is undeniably true—and it is an asset! If you want to see a film about a boy and a girl talking their way into love, discovering each other, there are thousands around. Netflix is lousy with them. There are Hepburn and Tracy knock-offs just lying around the place. Love Actually is about, largely, the period before people get to know each other.

And here we arrive at the answer to the question, why does Love Actually matter?

So, you meet someone and feel something instantly and then you imagine a thousand conversations in your mind and you become enamored with a fantasy and you know it’s a fantasy but as you get to know the person really every new thing you learn seems to reaffirm the fantasy and maybe the fantasy isn’t just a fantasy and you know it’s crazy but wouldn’t it be nice if it weren’t crazy and your life really could be like a sonnet, like a pop song, like Paris in the ’20s, and maybe, just maybe, if you wish upon a wish and hope beyond hope, that person is actually as crazy as you and is having all the same thoughts as you and just hasn’t expressed them because they know they’re crazy too and it’s society’s fault really and maybe you should send them some sort of signal like a wink and a nod or a coded message to find out if they’re with you on this whole rising tide of affection thing or maybe–even better!–you should just stop being such a coward and make some romantic gesture that demonstrates your courage because people like to have sex with people who have courage and then you’ll both move to West Egg and have brunch together every single day.

But then the optimism gives way and you remember: There will be no brunch, you fool. You will not move to West Egg, you child. That person almost certainly does not return your clearly irrational affection. They are probably emotionally mature. Daddy probably went to their recital and they have self-worth and they are grown-up and you clearly are not and the world is a cold dark place and Kate Winslet’s character dies in the end of Revolutionary Road and love was created by Hallmark, the Beatles, and Big Valentines Day and you are a fundamentally silly individual so stop.

That romantic gesture? Stop. Do not let them know that you have had any of these thoughts, just stop. Don’t let them know you have any affection at all, just stop. For real, don’t, stop. From personal experience, don’t, stop. You’ll look like an idiot; stop. You’ll embarrass yourself; stop. You’ll humiliate the other person; stop. You’ll enter a vicious shame cycle, stop. It will involve lots of Sinead O’Connor and dark grain alcohol; stop. You’ll gain a lot of weight; stop. Your hair will gray; stop. Then one day you’ll die—stop—poor and alone—stop—haunted by the memory of that time you drove off your one chance for happiness.

And so you stop.

Do the last three paragraphs sound totally foreign to you? Then Love Actually isn’t your film! It is wish-fulfillment for the oft-disappointed unlucky ducks who think like this. And people do think like this. They think they’re crazy and they think they’re the only ones who do it, but they’re not. Love Actually taught me that. It might just be me and Richard Curtis, but I have a striking suspicion there are at least few others too. And that’s why Love Actually matters.

Love Actually says, yes, you’re crazy, but other people are crazy, too, and you should find out if maybe they’re crazy about you.

This thesis is on greatest display in the denouements of four of the film’s storylines: Hugh Grant’s David races down “the dodgy end” of Wandsworth and finds Martine McCutcheon’s Natalie and goes to the school play with her and the octopus kid and they kiss but only after he is moved by a note she writes him. “If you can’t say it on Christmas when can you say it, eh?–I’m actually yours.” Can say it. It isn’t about finding the words, it’s about finding the courage to use Christmas as the excuse to tell him that she “like likes” him on the off chance that she isn’t the only one feeling all the feelings. One can imagine another version of the film that focuses on her side of the interaction instead of Grant’s. This is her crazy romantic gesture: a Christmas card. We know, but she can only hope, that Hugh Grant has been nuts about her from day one.

Colin Firth’s Jamie flies to Portugal and proposes to Lúcia Moniz’s Auréalia. In broken Portuguese, he admits the obvious: “I know I seems an insane person because I hardly knows you.” He does seem insane. The level of his affection is irrational and he knows that she is probably less irrational than he. “Of course I don’t expecting you to be as foolish as me and of course I prediction you say no but it’s Christmas and I just wanted to…check.” Lo and behold, she is just as foolish as him! Dare to dream, kids, that your irrationality is not unique.

Liam Neeson’s Daniel explicitly implores Thomas Sangster’s Sam to tell the girl that he loves her. “No way!” the boy says. “Sam, you’ve got nothin’ to lose, and you’ll always regret it if you don’t! I never told your mom enough. I should have told her everyday because she was perfect everyday.” “Okay, Dad. Let’s do it. Let’s go get the shit kicked out of us by love.”

Of course, Sam doesn’t get the shit kicked out of him by love. Joanna does know his name and she kisses him on the cheek and then he and his stepfather hug and it’s all very lovely. But the oft-derided Keira Knightly storyline provides us with a more shit-kicked case.

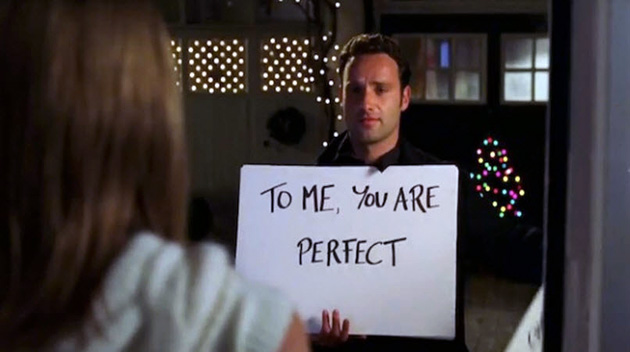

Mark (Andrew Lincoln) is in love with his best friend’s wife, Juliet. He has kept it to himself but she finds out, naturally, and then he goes and secretly tells her how wonderful she is.

Here’s Orr:

“I’m barely scratching the surface of what’s wrong with this subplot—the movie’s worst—which somehow manages to present the idea that it’s romantic to go behind a friend’s back to ostentatiously declare your everlasting love for his wife.”

Sure, yes: bad friend. But also, it is romantic! It may be romantic and evil, but it’s still romantic! (And, Chris Orr, this is the saddest part of the movie because that guy is all of us, all of us who have ever loved the wrong person for the wrong reason. If you don’t feel the teensiest bit of empathy for him, well, you’re made of very stern stuff.)

As Alyssa Rosenberg notes at ThinkProgress, “When Mark tells Juliet he loves her, she goes back to her husband, because wanting someone doesn’t magically compel them to throw over their lives in order to be with you. The gesture is fundamentally about Mark, just as his entire infatuation has been.”

And after he gives his little speech, what does he say? “Enough. Enough now.” He has been released. He has, in a very real sense, had the shit kicked out of him by love and he is the better for it. Again, the film is arguing for the benefits of not keeping everything inside. You’ll feel better even if your affection isn’t returned.

Indeed, Love Actually is the most pro-romantic film ever. It is a clarion call to share your pent up feelings for other people. That is good. That is decent. That is rare. People like to be told that they’re thought of as wonderful, that they matter to someone else. People should do it more often. And sure, they probably don’t feel the same way about you, but you should find out. Just in cases.