You know the drill: We see, we read, we recommend. We asked Mother Jones staffers to write up some of their favorite books of the year, and so here they are. While you’re at it, don’t miss music critic Jon Young’s Top 10 Albums of 2013. Also coming this week: a roundup of the year’s best photobooks, courtesy of our contributing photographers, plus Asawin Suebsaeng’s movie picks for the year.

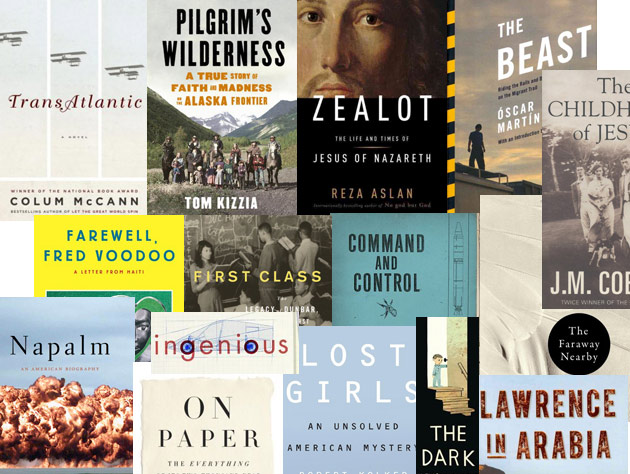

Pilgrim’s Wilderness: A True Story of Faith and Madness on the Alaska Frontier, by Tom Kizzia. Into the Wild meets Little House on the Prairie. Sort of. Tom Kizzia, an enterprising newspaper reporter, happens upon a family of 16 homesteading deep in the Alaskan range—on national park land, it turns out—and realizes the “Pilgrims” are not what they seem. A tale of manipulation and intrigue unfolds, one that has echoes of Elizabeth Small and Charles Manson, but all in the family. —Elizabeth Gettelman, public affairs director

The Beast: Riding the Rails and Dodging Narcos on the Migrant Trail, by Óscar Martínez. La Bestia (the Beast) is what migrants call the freight trains that traverse Mexico, where, as Salvadoran journalist Óscar Martínez chronicles in terrifying detail, messing with the wrong people—police, bandits, Los Zetas—can mean a violent end to the journey north. Starring trafficked prostitutes, cartel-threatened coyotes, and clear-eyed Border Patrol agents, The Beast is a harrowing on-the-ground look at the migrant trail. —Ian Gordon, copy editor

Farewell Fred Voodoo: A Letter from Haiti, by Amy Wilentz. I picked up journalist Amy Wilentz’s ode to Haiti and put it down for a while. Picked it up, put it down. But not because it wasn’t heartbreaking and gorgeously written and filled with fascinating insights and characters. Because it is. Perhaps it was the feeling I got when I imagined myself in the shoes of that nation’s desperate people. But if you’re going to read any Haiti book this year besides Mountains Beyond Mountains, this is the one. —Michael Mechanic, senior editor

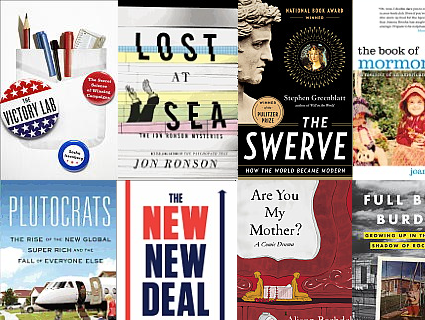

Command and Control: Nuclear Weapons, the Damascus Accident, and the Illusion of Safety, by Eric Schlosser. From the guy who brought us Fast Food Nation, this nonfiction must-read moves like a thriller. As I noted in a longer review (where you also can read the first chapter), Eric Schlosser’s historical investigation of America’s nuclear weapons mishaps scared the pants off me. But look at the bright side: This kind of stuff can’t still happen? Don’t bet on it. I could barely put this one down. —MM

On Paper: The Everything of Its 2,000-Year History, by Nicholas A. Basbanes. The contradictory nature of paper is just one of the fascinating aspects of this book. Paper is the thing and not the thing, as its worth “relies almost entirely on what has been written, drawn, or printed on its surface.” Nicholas Basbanes recounts dozens of the 20,000 documented uses for paper, and reminds us that bound up in the most mundane of objects, there is the potential for the deepest of human expression. This thorough exploration of one of our greatest inventions is worth reading—yes, on paper. —Claudia Smukler, production director

The Faraway Nearby, by Rebecca Solnit. When I first picked up this book, I almost dismissed it. I was afraid to read about someone else’s aging mother, given my own struggle caring for one. But Rebecca Solnit is a master and The Faraway Nearby is a generous gift to the reader. Solnit’s multi-layered narrative moves nimbly through this emotional terrain as she weaves bits of her life and travels with dreams and fairy tales, unexpected opportunities, and loosely assembled stories within stories. Gratitude replaced my original reluctance, and by the time the book circles back to her mother and the resolutions that come with time, I cried, hearing a moving symphony in my head. —CS

Napalm: An American Biography, by Robert M. Neer. In the era of drone strikes, Napalm is a timely look at what it means to (literally) rain death from above. Developed at Harvard during World War II, napalm was explicitly designed to destroy civilian targets: It was even tested on mock-ups of German and Japanese houses. The horrific firebombing of Japan and the use of napalm in Vietnam figure prominently, but the book also details lesser-known uses of the weapon in Korea and Iraq (where the US military insisted its “firebombs” were different than napalm). An excellent and disturbing history of a weapon that’s synonymous with the horror of modern warfare. —Dave Gilson, senior editor

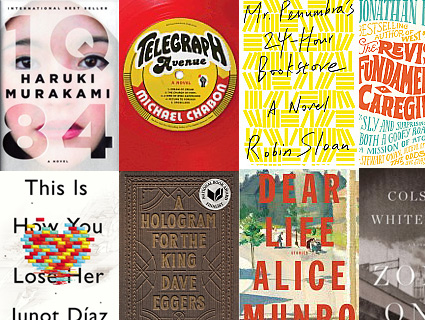

Zealot: The Life and Times of Jesus of Nazareth, by Reza Aslan. Even without the ridiculous controversy over whether Reza Aslan, a Muslim, had the right to write it, Zealot deserved attention for popularizing the fascinating yet relatively obscure academic quest to reveal the “historical Jesus.” Aslan engagingly offers his own take, arguing that Jesus was not a pacifistic, messianic figure offering salvation but a militant, worldly leader advocating liberation from Roman rule—a political offense punishable by crucifixion. Aslan’s critical perspective is not a repudiation of Christianity but rather a call to more fully understand why this first century Jewish rabble-rouser wasn’t lost to the ages. —DG

Lawrence in Arabia: War, Deceit, Imperial Folly and the Making of the Modern Middle East, by Scott Anderson. If you’ve ever wondered how the Middle East became so conflict-ridden and the cause of so many of the globe’s geopolitical headaches, journalist Scott Anderson’s deeply researched, elegantly written, and sweeping tale of the adventures of T.E. Lawrence and other European plotters who vied for advantage in this region during the First World War will explain much. In one of the most marvelous nonfiction works of the past decade, Scott Anderson focuses on the compelling and tragic story of the world’s most famous Arabist—busting cinematic myths where necessary—and shows how the actions of a few (despite Lawrence’s best intentions) yielded decades of challenge and anguish. —David Corn, DC bureau chief

Super Graphic: A Visual Guide to the Comic Book Universe, by Tim Leong. You don’t necessarily have to be a comic book fanatic to enjoy this fun infographic collection from Wired‘s former director of digital design. The pages are filled with entertaining and creative charts, such as “The Pizzas of the Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.” In order to complete Super Graphic’s pages, Leong lived a dual life similar to that of a super hero. “I had to come straight home [from Wired] and design charts until 3 a.m. several nights out of the week,” he told Mother Jones. Those late nights proved well worth it. —Brett Brownell, multimedia producer

Lost Girls: An Unsolved American mystery, by Robert Kolker. My favorite beach read of the summer, Lost Girls is ostensibly a true-crime tome about a number of women who started working as prostitutes and escorts through Craigslist and ended up washing up dead in Long Island. But the serial-killer angle is not the reason to read the book. Lost Girls is really a chronicle of what happened when the bottom dropped out of the economy in semirural (and, okay, white-trashy) communities. It’s a story of quiet desperation told well, and with compassion. —Stephanie Mencimer, reporter

First Class: The Legacy of Dunbar, America’s First Black Public High School, by Alison Stewart. Having lived in DC for more than 20 years, I still often feel like I’m just scratching the surface of the “real” DC, as opposed to federal Washington. This book did wonders for my understanding of local history, not to mention black history. Alison Stewart, a journalist whose parents attended Dunbar, does a marvelous job of tracing the fight for racial equality through the story of the nation’s first black public high school. It’s a gem of a book. But don’t take my word for it: Bill Clinton gives it a glowing review, too. —SM

Ingenious: A True Story of Invention, Automotive Daring, and the Race to Revive America, by Jason Fagone. I had to hold myself back from Googling the 2010 Progressive Automotive X Prize to see which of Jason Fagone’s colorful characters (get a taste here) would win it. In this great race, a motley crew of crews compete for a share of the $10 million prize, whose goal was to jumpstart development of a practical 100 mpg car. I don’t know how practical any of them turned out to be, but the book is a great ride. —MM

The Dark, by Lemony Snicket; illustrated by Jon Klassen. Allow Lemony Snicket (a.k.a. Daniel Handler, author of the “Unfortunate Events” series) and artist Jon Klassen to introduce your kids to the darker corners of your house—and their imagination. Little boy Laszlo, alone in the starkly drawn house, is joined only by the creaks and cracks and mysteries of the invisible, brought to life by Snicket’s lyrical machinations. It’s recommended for kids three to six, but my twins are two, and they’re fans. —EG

TransAtlantic, by Colum McCann. What at first reads as a series of extremely engaging short stories fictionalized from historic moments and figures—the first flight across the Atlantic, Frederick Douglass visiting Ireland—slowly reveals itself as a cross-generational journey, and opportunity for one woman and her female descendants ties these historic moments together. Though not a light romp, the prose and well researched subject matter make for a very enjoyable read. —Emma Logan, director of human resources and administration

The Childhood of Jesus, by J.M. Coetzee. In his latest, the South African Nobel laureate uses his icy, pitch-perfect prose to create a mysterious, Kafkaesque world inhabited by exiles living materially stripped-down lives administered by friendly but implacable clerks. The plot is oddly engrossing—and utterly enigmatic. If you don’t go in a fan, you may hate it. Coetzee-heads like me will find it haunting. —Tom Philpott, food and ag correspondent

Marcel Dzama: Sower of Discord, by Marcel Dzama, with contributions by Raymond Pettibon, Dave Eggers, Bradley Bailey, and Spike Jonze. Even if you don’t read a word of the stories and commentary that accompany this coffee-table retrospective, you will find plenty of weirdness and intrigue in the young, multitalented Canadian’s plates, collages, sculptures, costumes, and more. His artwork is by turns childish, violent, sexy, mischievous, and a bit disturbing—but never, ever boring. —MM

Vampires in the Lemon Grove, by Karen Russell. Flannery O’Connor said of Kafka’s Metamorphosis: “The truth is not distorted here, but rather a certain distortion is used to get to the truth.” O’Connor may as well have been talking about Karen Russell, whose tales in Vampires in the Lemon Grove flirt with the fantastical, but are rooted in darker realities—loss of innocence, PTSD, all-consuming ambition. The Swamplandia! author’s quirky imagination (see our interview) knows no bounds: In these tales, dead presidents wake up as horses and enslaved women morph into silkworms. But even as she transforms the everyday into a wriggling bestiary, replete with colorful hallucinations and ghosts, her most haunting bits rely on the depiction of human impulses. This collection is a great gift for fans of literary science fiction and magical realism, and lovers of writers like Haruki Murakami, Kelly Link, Aimee Bender, and Gabriel García Márquez. —Maddie Oatman, research editor