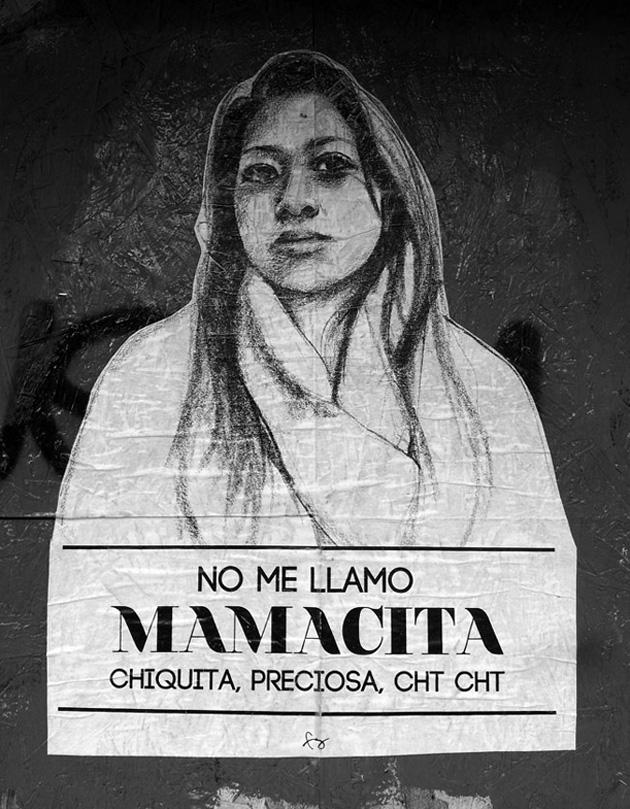

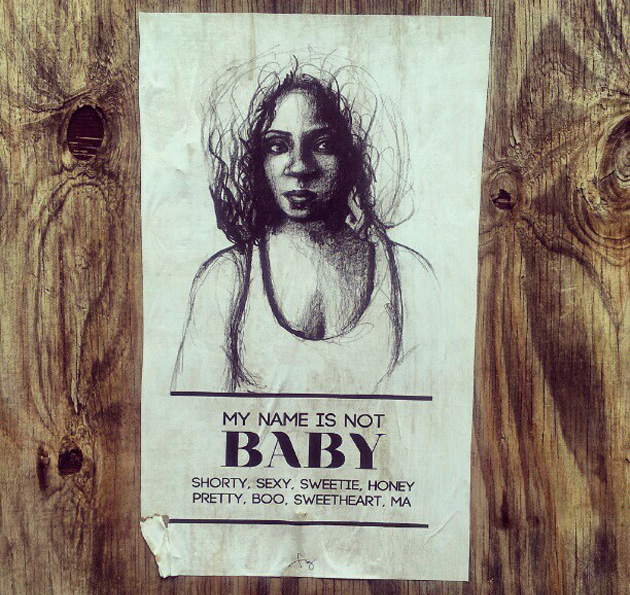

Tatyana Fazlalizadeh's self-portrait.All photos courtesy of the artist.

For many women, just walking down the street can mean being subject to harassment by men—from subtle comments to overtly hostile remarks. Back in 2012, fed up with such treatment, Tatyana Fazlalizadeh, an oil painter by trade, decided to speak out: She produced an illustrated self-portrait with a caption—”Stop Telling Women To Smile”—and plastered copies all around her Brooklyn neighborhood. Since then, Fazlalizadeh has created countless posters, literally taking to the street to combat sexist harassment. Each piece features a different woman, with a caption that reflects her own experiences with public harassment. With $35,000 raised on Kickstarter, Fazlalizadeh has now taken her project, named after that first caption, on the road. In January, after visiting Chicago and Boston to interview women there about how they experience public spaces, she’ll be headed to the West Coast to gather further inspiration for her posters.

Mother Jones: Are your poster captions direct quotes from the women depicted?

Tatyana Fazlalizadeh: Some are, but most of them are kind of inspired by my conversations. I sat down and came up with a caption that I thought would fit well on the poster—something that was short and succinct but got a point across. The latest poster was a direct quote—it was exactly what the woman told me.

MJ: These posters have mostly appeared in Philly and Brooklyn, but you’ve also taken the project to Chicago and Boston. Do the women have similar experiences no matter where they live?

TF: Yeah. All of the women have felt like, you walk outside of your home and it’s almost like you’re being attacked and there’s nowhere to turn. You’re treated as though you’re just a piece of meat, and you’re there for consumption by men. I feel like the common thing is men feeling entitled to treat you how they want to treat you. You never feel as though you have a right to the space. And so that’s the theme behind most of the posters—”I’m not outside for your entertainment” and “I’m not seeking your validation.” Depending on where you live and how you travel—whether you drive or bus or whatever—your experiences may be different. But I think that theme will be the same.

MJ: What kinds of differences have you found, say, between the women in Chicago and Boston?

TF: When I first landed, I met with a group of women in each city, and we had a big open conversation. In Boston, a couple of the women were students and they mentioned how Boston has a huge student population, and that’s specific to their experiences of street harassment. They feel like the men were a lot more aggressive, particularly when it comes to social outings and things like that. In Chicago, a few of the women invited me to a separate conversation with them and their friends, who were queer women of color. It opened up thoughts about the micro-issues like transphobia, homophobia, or fat phobia within street harassment.

MJ: Yes, I’ve noticed that many of your poster subjects are women of color. Did you intend that as your focus?

TF: Not necessarily the focus, but it was important to have these images and voices in this project. I’m a woman of color. I’ve lived in black neighborhoods all of my life, and most of the time I get hit on in my neighborhood—and mostly by black men. And so I wanted to have my specific experience and my perspective on street harassment out there. I also feel like this is a feminist issue and is going to be a part of a feminist conversation, and I wanted images of women of color in that conversation—feminism historically has left us out. And I’m learning more about how race is a part of street harassment, and how the differences between what a woman looks like and who she is affects how she is treated outdoors. So black women, Mexican women, Indian women, mixed women and their stories have been part of the series, and as the project continues there will be even more diversity. There’ll be queer women, trans women, all of these women who have different perspectives.

MJ: How do you think her race affects a woman’s ability to move through public spaces?

TF: Well, specifically for black women, our images and our bodies in the media and in history have been so hypersexualized. I feel like we’re looked at as either completely nonsexual characters or overly sexual characters, and I feel like that affects how we’re treated in the public space by men. I believe that women of color experience street harassment in a very hyper way. So I wanted to draw these women in their very normal, regular states and put those images out there in the public for people to see, instead of these other, very sexualized, images of women.

MJ: What do you think the street aspect of your project accomplishes, as opposed to, you know, canvas on gallery walls?

TF: There’s a huge difference. I am primarily an oil painter and a studio painter, so originally I was going to do an oil painting. It just kind of came to me to do it outside in the street. Men who are offenders of street harassment and women who experience street harassment can walk by and feel something about it, because it’s out there in the environment where the harassment actually happens. So it’s a lot more powerful than an oil painting that’s stuck in a gallery or under my bed or in my studio where only a couple of eyes are going to see it, as opposed to it being in an environment where it could possibly effect a change.

MJ: Part of your Kickstarter campaign was to raise money to get video footage of your travel and your conversations with women across the county.

TF: Yeah, I think it’s very important to get this stuff on film, not just the behind-the-scenes of the process, but also the interviews with the women. We’re going to try to do some on-the-street filming, getting people’s reactions to the work, and seeing if we can get some street harassment happening on film so people can see what we’re talking about. It’s important to have some type of documentation so people can see what happens when we create this artwork and why I’m creating it.

MJ: Your Kickstarter did incredibly well, so I’m wondering what kind of feedback you’ve received. Has there been any backlash from men?

TF: I’ve generally gotten negative feedback from men who don’t understand and don’t find street harassment to be a serious issue. I’ve also gotten a lot of responses from women who are appreciative and thankful for the project; who relate to it who are passionate about it. It’s been kind of extreme—people either love it or they don’t like it at all—and I think that’s a good thing. It’s my first art project where there’s not a middle ground. I find it very interesting. But the negative feedback hasn’t at all kept me from doing it, obviously. Because I haven’t really gotten any negative feedback that I feel is really warranted. Most of it has been men who don’t really understand, or they don’t like a woman speaking out about her experiences or trying to stand up for herself and take agency over how she’s interacted with outside. I just don’t really pay attention to that. I’ll definitely pay attention to someone who is critiquing the artwork. But as far as someone not thinking street harassment is a big deal or that I’m being uptight? I don’t think that’s a valid critique.