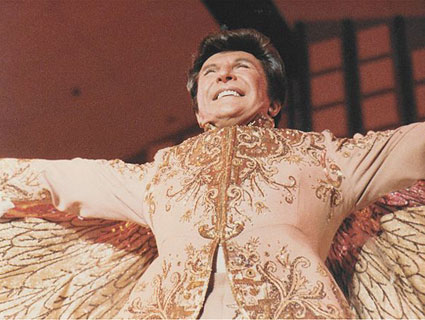

Graham Whitby Boot/Allstar/ZUMA Press

The movie was simply too gay.

That’s why director Steven Soderbergh says Behind the Candelabra, his latest (and possibly last) film, was not shown in American theaters. When the major Hollywood studios declined to pick up the biopic—which stars Michael Douglas as the famous Vegas showman Liberace and Matt Damon as Scott Thorson, his much younger boyfriend—HBO snapped it up. The film premiered on the cable network last month to critical acclaim.

Two weeks ago, after I published a review of Behind the Candelabra that highlighted Soderbergh’s claim that the movie was too gay for Hollywood, I started receiving messages from Hollywood insiders who said Soderbergh was lying. Some claimed that Soderbergh had never pitched his Liberace project to their studio. Others, including Mark Fritz, a director of theatrical sales and distribution for Warner Brothers International, objected to the charge that the film was rejected by major studios because it was too gay. “Sorry, but it is completely untrue that this film was deemed ‘too gay’ by Hollywood,” Fritz tweeted in response to my review. Fritz also dismissed Soderbergh’s claim as tantamount to absurd “conspiracy theories.” Warner Brothers had originally developed the film in 2008 and 2009. (UPDATE: In an email sent after this story was published, Fritz said that he was not referring specifically to Soderbergh’s statement when he mentioned “conspiracy theories.” He said that “Warner Bros. celebrates and espouses diversity in all its forms,” and that he “has the utmost respect for both Soderbergh and Behind the Candelabra.”)

After hearing about the pushback, Soderbergh himself got in touch with me to set the record straight. He kicked off our chat with a sarcasm-drenched tirade, describing an alternate reality in which the Hollywood version of why Behind the Candelabra didn’t get picked up might be believable:

“I usually let this stuff slide, but this just sounded too fascinating to let drop,” Soderbergh tells Mother Jones. “Since I’m a big fan of conspiracy theories, I propose a counter conspiracy theory: Warner Brothers never developed [the script for Behind the Candelabra] and didn’t…put it into turn around. [Producer] Jerry Weintraub did not spend six months working with a woman named Cathy Morgan to sell territories all over the world with contractual contingencies that these deals would be voided if we didn’t have a domestic partner…I never had a conversation that the economics would not work because the audience [for this film] was too limited. Everybody in town was not aware that this project was available, despite the big names attached. And we never wanted to make this a theatrical release because I never wanted [Matt Damon and Michael Douglas] to be eligible for Academy Awards. That’s my counter conspiracy theory, and your readers can decide which of these two theories is more plausible.”

Here’s what Soderbergh says actually happened: Warner Brothers (which, like HBO, is a subsidiary of Time Warner) began developing the movie over four years ago. But Soderbergh says that in 2009 Jeff Robinov, a top Warner Brothers executive and a close friend of the director, said that the Liberace project wasn’t for them. “We don’t see it,” Soderbergh recalls Robinov saying. (Robinov has not responded to requests for comment.) After that, Soderbergh and company had the studio’s blessing to shop the movie around to see who might want to distribute the film in the United States. And according to Soderbergh, every major studio that his team contacted responded with either silence or an outright no. “Everybody knows everything in this business; everyone knew about this project, [and] if someone wanted to make it, it would’ve been made.” Soderbergh says. “Calls would go out when the movie became available, from the agencies repping the thing…They all came back with ‘not interested’ or with no call returned.”

In Soderbergh’s view, the reason you can’t see Behind the Candelabra in American theaters has as much to do with financially—though not politically—conservative executives as it does with the palate of the American movie-going public. “It’s all economics,” he says. “The point I was trying to make was not that anyone in Hollywood is anti-gay. It was that economic forces make it difficult, if not impossible, for people to think outside of the box…If audiences were going in great numbers to see stuff that was not down the middle, then everyone would be doing that…[Hollywood is] merely responding to what people are telling them they want to see!”

To anyone even vaguely familiar with how big-studio marketing functions, Hollywood’s anxieties about Behind the Candelabra shouldn’t come as much of a shock. “I will say that Warner Brothers in my experience tries to hold a slot or two every year for something that doesn’t seem to fit the typical mold of a studio movie,” Soderbergh says. “[Ben Affleck’s] Argo is a good example of that; [Soderbergh’s 2011 drama] Contagion is another. They seem to give themselves one or two slots of ‘What the fuck?'” But Behind the Candelabra seemed to be a bridge too far for Warner Brothers. The film features plenty of gay love and intercourse, including one sweaty, grunting sequence in which Thorson is taking Liberace from behind while the middle-aged entertainer offers him drugs.

Hollywood and major studios have a well-documented history of claiming they don’t know how to market films depicting explicit gay sex to a general audience, and the MPAA rating system—which can sink the commercial viability of a film with an NC-17 rating—does not react well to gay sex. Even Brokeback Mountain, a 2005 Oscar-winner, was tethered to a publicity strategy that went out of its way not to mention even the word “gay.” This shouldn’t be too surprising: The film industry also hasn’t fully come to terms with showing a black man and a white woman having passionate sex or dating on-screen. And films with predominantly black casts typically struggle, too.

After Behind the Candelabra, Soderbergh began his much-discussed pseudo-retirement from directing feature films. Since making his name with 1989’s Palme d’Or-winning Sex, Lies, and Videotape, Soderbergh has helmed a total of 27 films and become one of Hollywood’s most celebrated and prolific filmmakers, noted for his eclectic filmography (Traffic, Che, The Limey, the Ocean’s Eleven remake, Out of Sight, Erin Brockovich, Magic Mike, Haywire) and for a blazing art-house approach to commercial filmmaking. But in 2011, he announced that he wanted to end his career in Hollywood by the time he was 50 in order to focus on, among other pursuits, painting. Though he hasn’t definitively sworn off big studios for life, he is at the very least taking a hiatus to explore other endeavors such as live theater in New York City, maybe some more cable television, and his website Extension 765—a “one-of-a-kind marketplace” that sells “swag” and “booze.” (He has said that he would be perfectly content if Behind the Candelabra turned out to be his final motion picture.)

Soderbergh insists that his grievance with the big-studio system and status quo—as well as Hollywood’s response to Behind the Candelabra—aren’t his main reasons for ditching the business. “The main reason is a personal, creative one,” Soderbergh tells me. “I’m feeling like I’m not evolving…I’m not involved in the ways I feel is most important. I feel stuck, and the only way to tear down everything I’ve done and start from scratch is to just get out.”

But Soderbergh has been one of Hollywood’s biggest names for nearly two decades. The idea that he’ll make a clean break from his profession when he’s barely into his 50s strains credulity. When asked whether he sees himself eventually returning to Hollywood—or to made-for-TV films, or perhaps to the indie scene where he got his big break in the ’80s—the director leaves his options open: “I have no idea. I gotta figure this out first,” he says. “Maybe this is my version of theism; maybe I’m just chasing nothing.”

For the next few weeks, the famously busy Soderbergh has a bit of downtime. (The man’s idea of downtime apparently includes mulling a cable TV project starring Clive Owen and re-editing his Franz Kafka biopic from 1991.) As for his peers and the aspiring filmmakers who haven’t ejected themselves from the system, Soderbergh offers this parting advice: “That’s your job, to navigate those rapids, and not turn your boat over and drown…You can’t find anybody working in the film business who says it’s as fun today as it was ten years ago. Everyone I know—agents, filmmakers, executives—just talks about, ‘Man, it’s not as fun as it used to be.’ And it should be fun. We’re making entertainment for people. Why can’t this be fun?”