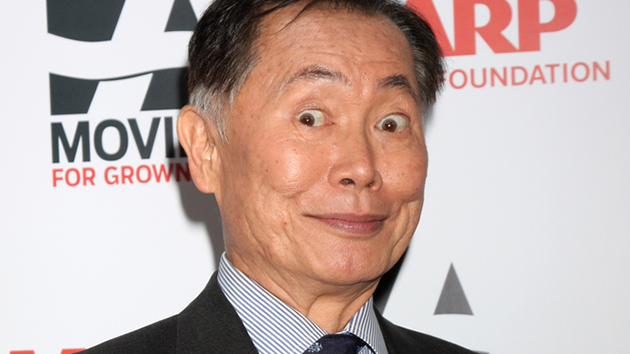

George TakeiShutterstock/Helga Esteb

Back in the 1960s, when actor George Takei landed the part of Hikaru Sulu on Star Trek, he knew how lucky he was. Sulu defied the two-dimensional stereotypes that infused most of the roles then available to Asian American actors, and Takei knew from experience how insidious those stereotypes could be. He has clear childhood memories of men with guns arriving at his Los Angeles home post-Pearl Harbor to haul the family away—first to a horse track in Arcadia and later to a United States internment camp in Arkansas—and has since been active in efforts to remind people about what happened in America during that dreadful time. Takei, who is gay, also has been an outspoken champion of LGBT rights. His irresistible persona, and Star Trek‘s host of loyal fans, have contributed to Takei’s huge online following, which the self-described “Queen of Meme” hopes will help him bring his latest endeavor—a musical about the Japanese internment opening September 19 at the Old Globe in San Diego—all the way to Broadway. I spoke with Takei about his theater obsession, Asian drivers, and William Shatner’s gaydar fail.

Mother Jones: I can’t believe I’m talking to someone with 2 million Facebook fans!

George Takei: Obviously the Star Trek fan base—the geeks, as they call themselves—is large. I’ve also been vocal on issues of equality for LGBT people, and I consider it my mission in life to make Americans aware of Japanese internment, that dark chapter of American history.

MJ: Hence your starring role in Allegiance, your new musical about a Japanese American family in an internment camp. How did that come about?

GT: When my husband Brad and I are in New York, we practically live in the theaters—we’re there almost every night. One night there were two guys sitting in front of us and one of them recognized my voice. He was a composer-lyricist who had a musical on in San Francisco, and the guy with him was his producer. The next night we went to see a Tony-award-winning musical about a Puerto Rican family in Washington Heights. The same two guys were in the very same row as us. Near the end of the first act the father sings a song, “Inútil”—which means “useless.” He wants to do so much for his children and he feels he can’t because of economic circumstances and the various hurdles that he faces. And that suddenly triggered a memory for me of my father in the Arkansas internment camp. I’m one of these people who doesn’t just sniffle, I bawl, and I lost it. Of course the intermission comes and the lights blaze up immediately—I think it’s done maliciously fast when there’s a scene like that—so I was quickly wiping my face when the two guys came climbing over the knees of people to chat with us again. The composer-lyricist is an Asian guy and he said, “How did that song strike you so deeply?” I told him. We started talking, and the idea of doing a musical was born.

MJ: I’m always surprised by how many people are oblivious to the internment.

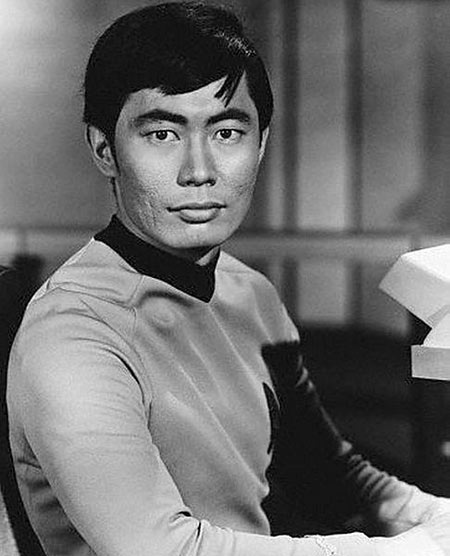

George Takei as Mr. Sulu NBC Television/Wikipedia CommonsGT: Yes, for America it’s a shameful experience—embarrassing—and for some non-Japanese Americans, it’s something they don’t like to talk about. For example the attorney general of California at that time was very ambitious, he wanted to become governor. He saw that the single most popular issue was “getting rid of the Japs,” and he used this to get elected. After two terms he went on to become Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. His name was Earl Warren—a so-called liberal justice. He was prodded and challenged by Japanese Americans throughout his career. He only spoke about it when he was near the end of his life. That’s one reason why our history books are rather mute.

George Takei as Mr. Sulu NBC Television/Wikipedia CommonsGT: Yes, for America it’s a shameful experience—embarrassing—and for some non-Japanese Americans, it’s something they don’t like to talk about. For example the attorney general of California at that time was very ambitious, he wanted to become governor. He saw that the single most popular issue was “getting rid of the Japs,” and he used this to get elected. After two terms he went on to become Chief Justice of the United States Supreme Court. His name was Earl Warren—a so-called liberal justice. He was prodded and challenged by Japanese Americans throughout his career. He only spoke about it when he was near the end of his life. That’s one reason why our history books are rather mute.

Also, Japanese Americans of my parents’ generation didn’t talk about that experience with their children. I was fortunate to have a father who did. Here’s an example of a very revealing situation: I was walking through the internment camp gallery at the Japanese American National Museum where I’m a board member and I noticed there was an elderly gentleman, a middle-aged man, and two preteen boys in the internment camp gallery. The boys were asking, “Grandpa, you were there?” The father of the boys, the son of the elderly man, was saying, “Dad, you never told me that!” He could not tell his own son when he was growing up. Now with the passage of time and a respected museum setting that had some dignity about it, grandpa felt comfortable enough to share with his grandsons what he could not tell his own son.

MJ: Maybe it’s because people feared that it could happen again.

GT: We sensed it immediately after 9/11. People react hysterically when a event of that magnitude happens. In our case, we just happened to look like the people who bombed Pearl Harbor.

MJ: What do you recall most vividly about your family’s internment?

GT: I still remember that very scary day when we were ordered out of our two-bedroom home on Garnet Street here in Los Angeles. Two soldiers came up to our front door. I was looking out the living room window and I saw them marching up our driveway and they stomped onto the porch and banged on the door and we were ordered out of our homes. We were taken to the horse stables of Santa Anita racetrack. My mother said that was the most degrading, humiliating experience—the whole family forced at gunpoint, literally, to live in narrow horse stall that still had the stench of manure.

MJ: And so you became an activist.

GT: I was involved in the civil rights movement way back in the late ’50s and through the ’60s and ’70s. I was doing a civil rights musical here in Los Angeles and we sang at one of the rallies where Dr. Martin Luther King spoke, and I remember the thrill I felt when we were introduced to him. To have him shake your hand was an absolutely unforgettable experience. Even before I could vote, I was involved in the political arena. My father was an admirer of Adlai Stevenson and he took me to the Stevenson for President headquarters and he volunteered me. That was my introduction to electoral politics, which was exciting and fun and thrilling, and very theatrical.

MJ: Speaking of theatrical, your videos skewering anti-gay laws and politicians are hilarious.

GT: Humor is a powerful tool, and some of these politicians are so far out and easy to lampoon. They just provide such delicious opportunity.

MJ: Tell me about the “It’s OK to be Takei” video.

GT: In Tennessee they have a whole cast of yahoo politicians. One named Stacey Campfield sponsored a bill criminalizing teachers using the word “gay” or “homosexual.” Well, if they’re going to ban the word gay, my surname rhymes with gay. So you can use Takei in its place and march in a Takei Pride Parade and at Christmas time sing “Don we now our Takei apparel, Fa, La, La, La, La, La-La-La-La.”

MJ: Were you out of the closet during Star Trek days?

GT: No. I was quietly out with a very small circle of my gay friends. I went to gay bars and I was a member of a gay running club, you know, but we knew the social climate. At bars I sometimes recognized other actors. We might nod and smile, maybe have a brief conversation but when we’d encounter each other on the studio lot we played as though that hadn’t happened.

MJ: Did the cast know you were gay?

GT: Most of them knew, but they were cool. They knew what impact it could have on an actor’s career. Once I was at work chatting with Walter Koenig, who played Pavel Chekov, and he started gesturing at a group of young extras who were dressed in the Starfleet shirt. There was a gorgeous young guy with a fantastic build and that tight shirt on him and that’s when I knew that Walter knew. I turned back to him and he was grinning. He was helping me out! Bill [Shatner] was oblivious. In fact, when he was on the Howard Stern Show, Howard had me call in and chat with Bill. I mentioned Brad and he didn’t know who Brad was. Everybody knew! We had a very public wedding. Bill says, “Who’s Brad?”

MJ: Sulu never had a romantic attachment on the show, right?

GT: You’re right. During the first season I lobbied Gene Roddenberry and the directors and the writing staff to beef up the role—well, everybody was doing that, and when you have seven regulars it gets to be very difficult. Gene said, “This is the first season and we really have to strengthen the two leads.” But he promised me that in the second season he’d devote more attention to the other characters. He did keep his promise and develop wonderful roles for Sulu. But I got cast during the hiatus in The Green Berets, the John Wayne movie. We ran way over schedule and I couldn’t be back in time for the beginning of the second season. Walter Koenig was brought in to essentially say the words that were written for me. I had already memorized them because I was so excited. When I came back I hated Walter sight unseen.

MJ: Did you work it out?

GT: We worked it out. As a matter of fact, we had a shortage of dressing rooms so they asked me to share my dressing room with Walter—a person who had stolen my part! But he turned out to be a really good friend.

MJ: Did you feel a sense of responsibility as the rare Asian face on television?

GT: Yes. Up until the time I was cast in Star Trek, the roles were pretty shallow—thin, stereotyped, one-dimensional roles. I knew this character was a breakthrough role, certainly for me as an individual actor but also for the image of an Asian character: no accent, a member of the elite leadership team. I was supposed to be the best helmsman in the Starfleet, No. 1 graduate in the Starfleet Academy. At that time there was the horrible stereotype about Asians being bad drivers. I was the best driver in the galaxy! So many young Asian Americans came up to me then—and still do today, although they’re not that young anymore—to tell me that seeing me on their television screen made them feel so proud. I lobbied to develop the character. I tried to get mentions of my family, to humanize the character, and because of the circumstances—like getting cast in a feature film with John Wayne—that really didn’t happen.

MJ: Did you ever feel tokenized?

GT: No, no. My father told me, “Don’t do anything that would bring shame to the family.” I was always mindful of that. When I told him I wanted to pursue a career as an actor, my father said, “Look at what you see on television at the movies, is that what you want to be doing? Do you want to make a life out of that?” And I said, “Daddy, I’m going to change it.”

MJ: I like how you connect your activism to your acting.

GT: It’s that image that created the perception that made it easier for the government to incarcerate a whole group of people. At that time, in comic books and radio dramas, we were depicted as cutthroat and coldhearted and cruel—unfeeling—or we were wily or suspicious or the buffoon. That was the general perception of Japanese Americans. We weren’t seen as Americans. If someone spoke without an accent, we were exotically Americanized foreigners. My father knew the importance of the image of Asians in the media and how that shapes perceptions. We were complicit in it at that time: We went out there and rented our faces out and played cruel Japanese soldiers or bumbling Chinese waiters.

MJ: Do your Trekkie fans show interest in your political issues?

GT: I didn’t think the internment story would connect with the geek community, but as it turns out it does. They feel like a minority community, so they understand.