In his portraits of sex workers and the homeless struggling with addiction, photographer Chris Arnade is neither demanding an increase in social services or gawking from the sidelines at others’ degradation. At their core, his “Faces of Addiction” portraits are simply about watching and listening to other people. Arnade repeatedly declares his one simple objective at the end of each detailed photo caption: “I post people’s stories as they tell them to me. I am not a journalist. I don’t try to verify, just listen.”

If his pictures challenge our expectations, maybe it’s because Arnade defies stereotypes, too. The child of Southern civil rights activists, he got a Ph.D. in physics from Johns Hopkins before becoming a banker. During our interview, he explained his tendency to cross boundaries, saying, “I’m happiest somewhere I shouldn’t be.”

A show of Arnade’s work opens March 10th, 2012 at Brooklyn’s Urban Folk Art Studios. The proceeds from the sale of his photos will be donated to the Hunts Point Alliance for Children. Arnade’s “Faces of Addiction” portraits can also be found on Flickr, and you can follow him on Twitter.

You live in Brooklyn and work as a banker, so how did you end up taking pictures in the Bronx?

I’ve lived in New York for 20 years and I’ve always loved exploring. For the last five years I’ve done it with my camera. I did a series on pigeon keepers, mostly in East New York, Bushwick, and also the Bronx, looking for pigeon guys.

Hunts Point is cut off from the rest of the Bronx. Some people have described it as a dumping ground. It’s quiet and you can get to know people very easily, but at the same time it has a lot of crime and a lot of prostitution and a lot of drugs. I had come in contact with a nonprofit called Hunts Point Alliance for Children. I started doing photography with them, and I got to know the [neighborhood] children.

When did you make the transition to photographing addicts and sex workers?

While photographing the children for HPAC, I was trying to document their struggles, the obstacles they face: the gap between Hunts Point and where they want to go. I haven’t taken pictures of this, because I don’t like to take pictures without consent, but at eight at night on any street corner you have four or five addicts who are prostitutes operating openly and kids have to walk by them.

When you first spend a lot of time in Hunts Point you’re very struck by the open-air drug use and large underground economy. The first time Takeesha, one of the prostitutes I photographed, approached me and asked me to take her picture, I was struck by her brutal honesty and awareness.

Looking at your images, there is a sense that you’re entrenched and embedded, like you have relationships with your subjects.

If I find a project or a neighborhood interesting, I generally spend time there first without my camera. Just walking around talking to people. If you can find one or two people and build relationships with them, they’ll take you to new parts. The other thing is to have no fear and just be open-minded. I know a lot of people who would never walk into a crack house. But when someone says, “Hey, there’s some addicts in that building,” I’ve just walked in. Maybe I’m naive, but I find that if you treat people with honesty and trust them with no stereotypes, they’re often disarmed and are willing to treat you just the same. If I see somebody who might be reticent at first, a lot of times I’ll hand them my camera and say, “Take a picture of me.” That act of handing them a $5,000 camera is a way of saying, I trust you.

I always tell people exactly what I’m doing. I say I’m going to put the photo online. I always go back, but keeping in touch with people is hard. Their lives are volatile—they’re often in jail, or in and out of rehab.

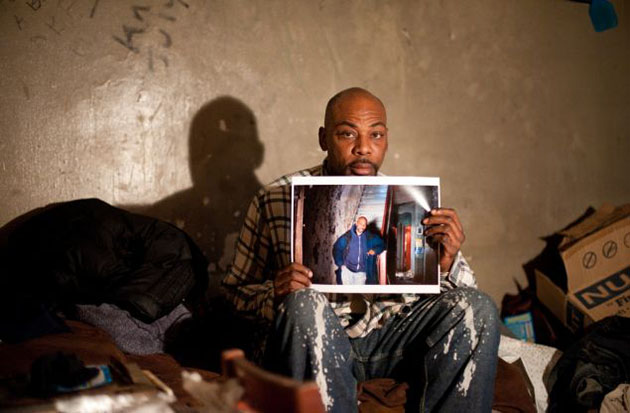

You also bring people the copies of the photographs you’ve taken, like the one Lamar is holding in a later photograph.

I always brought back pictures because I thought it was the moral thing to do. A lot of street photographers do the kind of “gotcha” pictures, which I feel is just not right. If you ask someone to let you take their picture, you owe them something. At a minimum, it’s a copy of that picture.

It’s also a good way to build trust in the neighborhood. Hunts Point is not huge. There’s a lot of reticence because the number of whites in the neighborhood is very small. Some people in the neighborhood call me “officer.” So bringing back the prints, bringing my iPad and showing them what I wrote about them certainly helped further the trust.

One of your subjects, Takeesha, talks about how she needs to go from Hunts Point to Mott Haven in the Bronx, to get back on Medicaid, but it’s too hard to get there. She said, “It’s, like, so simple to walk across the bridge, but it’s like you can’t go across.” Why do you think she feels this way?

Hunts Point is unique because it really is cut off geographically. To get to the rest of Bronx you have to cross over a rail yard and then under the expressway. When you’re in Hunts Point, you’re in another part of the Bronx. That’s why I liked Takeesha’s quote so much. If you’re an addict and you’re a sex worker and you’ve been in jail 156 times, you wake up in the morning and all you have to do is walk a mile—[to her] that’s the largest move in the world.

You photos and your captions seem to epitomize the overlap between drug abuse, homelessness, sex work, and poverty. Have you gained an understanding of the way these things are connected?

My views on these issues are in flux because of my experiences here. Sonia, who looks and acts like a librarian, says, “If I had all the money in the world I’d have all the crack in the world.” She’s saying, Look, I’ve been in and out of rehab, I was clean for eight years, I’m not lacking in resources in terms of help. I’ve got methadone, I’ve got people willing to help me but unless it comes from me it can’t happen.

When you don’t talk to someone, it’s very easy to judge them. You can build up a narrative where they kind of deserve what they got. When you talk to someone, it’s much harder. Jamie, one guy I’ve gotten to like a lot, lived underneath the Bruckner Expressway. Whenever I’d go back to see him, I’d bring him whatever he needed because the winters are tough. We’d smoke a cigarette and just talk. He had a cat, Mimi. Mimi was a female and looked like she was going into heat and I asked him if I could get Mimi spayed. Then I asked some people for help trying to get Mimi spayed. I kind of got more offers to help Mimi than I did to help Jamie. I appreciate all those offers, in both cases, and people have been very helpful for Jamie, but there’s the mentality that an animal doesn’t deserve what it’s gotten but a person does, because maybe they’ve done something to deserve that.