Read the backstory: Our interview with the collection’s curator.

These 19 images are but a small sampling of the comic treasure to be found in The Someday Funnies: A Comic History of the 1960s, out in November from Abrams ComicArts. The lavish book chronicles the long, strange trip of the collection of brilliant and subversive comics originally created for publication in Rolling Stone in the early 1970s. Michel Choquette, the book’s editor, describes it as a time capsule, and it’s hard to decide what’s more fascinating: the psychological and political preoccupations of the decade it depicts, or the stellar careers of the writers and artists whom Choquette was able to bring aboard. The contributors to this project have since distinguished themselves not only as comic artists, but as writers, editors, publishers, commercial illustrators, and film directors.

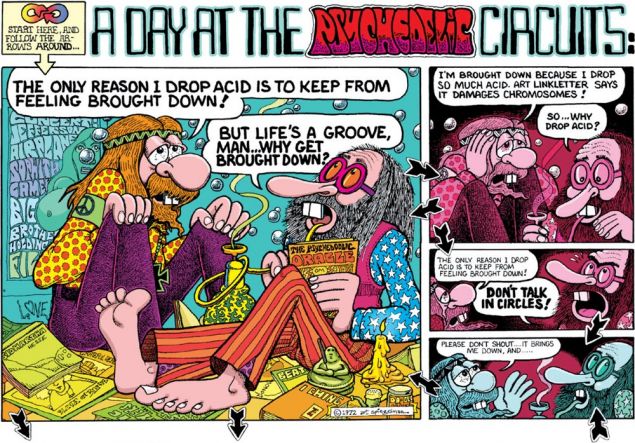

Detail from “A Day at the Psychedelic Circuits,” by Art Spiegelman. The artist, who won a Pullitzer Prize for his graphic novel Maus,” has created a formalist comic experiment in which readers are encouraged to create multiple narratives by changing the order in which they read the individual panels. Or it’s a story about an acid trip that eats its own tail.

Detail from “It Was All a Clever Ruse Comix”; text by Chris Miller, art by Gray Morrow. Miller, a screenwriter on Animal House, and Morrow, who had just finished a stint as the art director for the Spiderman comics, imagine a world of what-ifs, where, among other things, Lee Harvey Oswald sleeps in on November 13, 1963; John and Jackie Kennedy retire to the South of France; and Aristotle Onassis meets and falls in love with Janis Joplin.

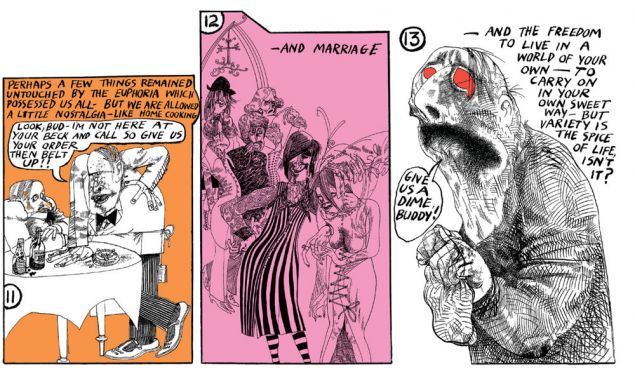

Detail from “The Man Who Peaked Too Soon,” text and art by Tom Wolfe. Better known for his role in the development of the New Journalism in the early ’60s and his many fiction and nonfiction books, Wolfe demonstrates here that he could also have had a career as a comics artist, while narrating the story of a man who garners nothing but abuse by anticipating some of the major trends of the ’60s and ’70s just a little too early.

Detail from “Kent State Karmics,” text by Douglas C. Kenney, art by Stan Goldberg and Dick Giordano. This comic juxtaposes the pleasures of college life (and drinking!) in the 1960s with the killing of four Kent State students by the Ohio National Guard on May 4, 1970. Goldberg worked at the time for Archie Comics, which the colored portions of this strip were satirizing; Giordano, who later became executive editorial director at DC Comics, drew the monochromatic panels. Kenney was a cofounder of National Lampoon.

Detail from “The ’60s,” by Ralph Steadman. A contributor to Mother Jones, Steadman releases his caustic wit and irrepressible lines on British society as it struggles to adapt to the ’60s. He began his notorious collaboration with Hunter S. Thompson in 1970, well before the genesis of The Someday Funnies, for a story on the Kentucky Derby for Scanlon’s.

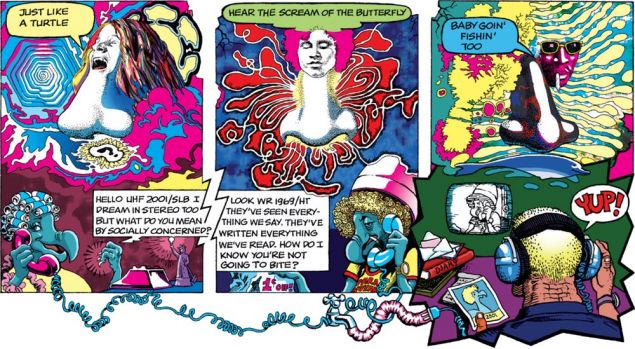

Detail from “Smell of the Sixties,” text by Ernie Eban, art by Jim Leon. I’d call this comic a mindbender: one where the artist tries to convey the twists, turns, and epiphanies of the psychedelic experience to a reader whose mind may or may not be similarly altered. This one combines a storyline about a dodo running a personals ad and getting her hair done, pop musicians like Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison, and Taj Mahal floating over giant noses in Dayglo skies, and a denouement involving a wiretapping operation. Eban was an Oscar-nominated British screenwriter, and Leon was a well-known surrealist painter during the ’60s and ’70s.

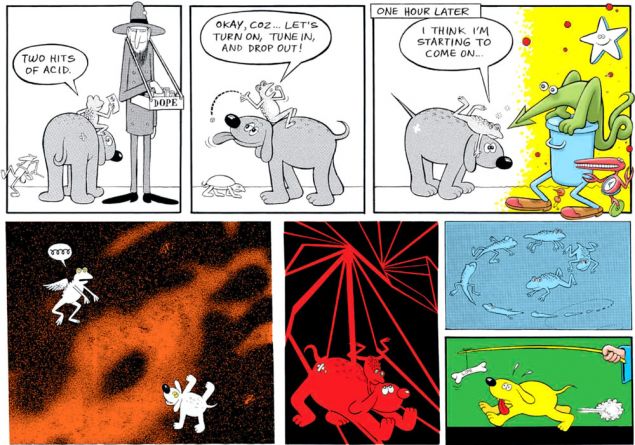

Detail from “Terry the Turgid Toad and His Sidekick Cosmic Dog in ‘Weird Trip,'” by Denis Kitchen. Another mindbender; in this one, a dog and a toad read about Timothy Leary and decide to drop acid. Kitchen is a prolific comic artist, publisher, and author, who founded Kitchen Sink Press, Denis Kitchen Publishing Co., and the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund.

Detail from “The Commune,” by Randall Enos. A vision of what happens when things like communes become popularized and the owners decide to “sell out.” After 46 years in the business, Enos is still doing illustration for, among others, Mother Jones.

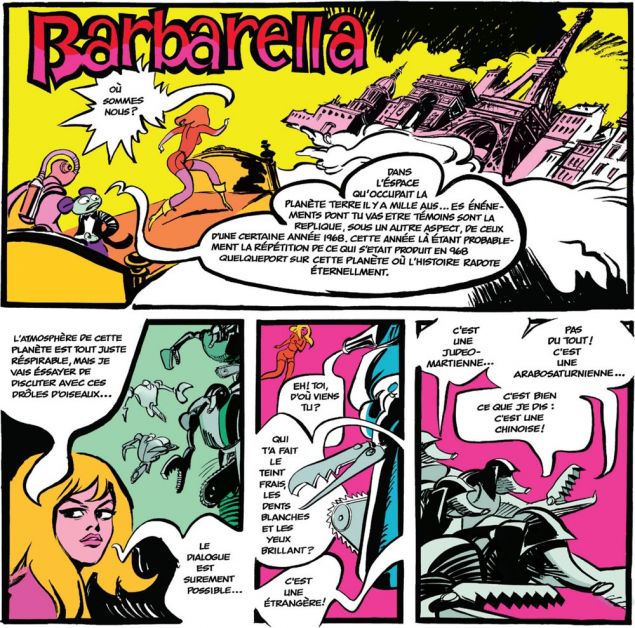

Detail from “Barbarella,” by Jean-Claude Forest. American audiences are more familiar with the Roger Vadim film of the same name, starring Jane Fonda, but Forest began publishing the popular comic strip in France in 1962. In this one, Barbarella is chased by hostile mechanical birds on an alien planet, while the French Student Uprising of 1968 is played out “in a different form” all around her. Daniel Cohen-Bendit, now copresident of the European Greens, makes a guest appearance in his 1968 identity as “Danny the Red.”

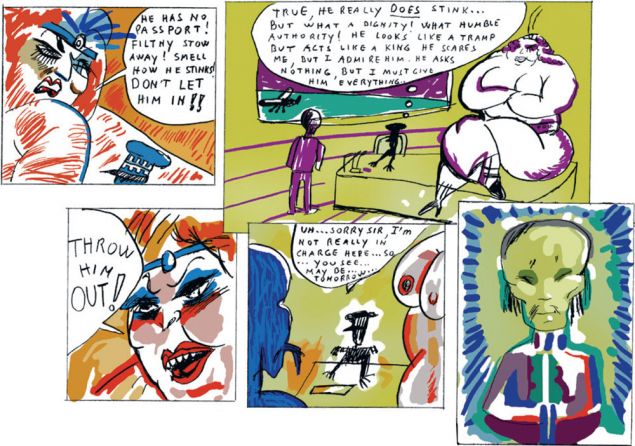

Detail from “A Dream I Had Ten Years Ago,” by Federico Fellini. The dream involves Fellini being made chief of the airport, and getting involved in a standoff between “the big mama-whore” and a “mysterious oriental.” It appears to be a metaphor for China’s finally being admitted to the United Nations. Fellini’s original artwork for this comic was lost in the mail; he obligingly redrew it.

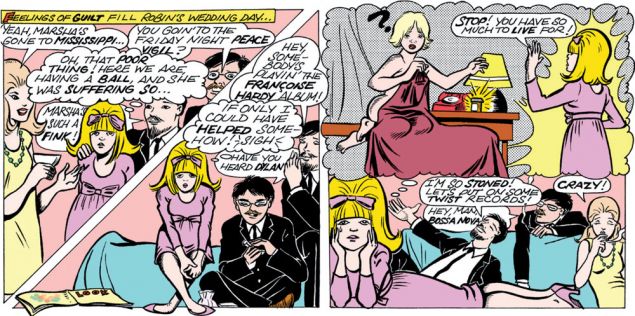

Detail from “Memories of Marilyn,” by Trina Robbins. A young woman hears about Marilyn Monroe’s suicide on her wedding day, and spends the day in a funk while her groom and friends party and get stoned. Robbins was active in the early underground comics movement, creating the first all-women comic book, “It Ain’t Me, Babe,” and has written several books on the history of comics, including “The Great Women Super Heroes,” and “From Girls to Grrrlz.”

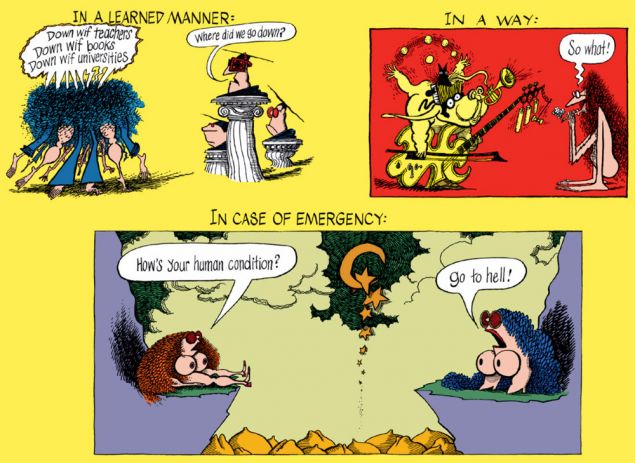

Detail from “Tolerance in the 1960s,” by Arnold Roth. Yet another mindbender comic, made up of a series of enigmatic single panels that can perhaps best be explained by John Updike’s comment that “the jazzman in [Roth] can be detected in the lyrical visual swoops and his preference for improvisation with the pen.” Roth is a widely published and well-known cartoonist and illustrator; in 2009 he was inducted into the Society of Illustrators’ Hall of Fame and he has appeared on The Tonight Show with Johnny Carson and on The David Letterman Show.

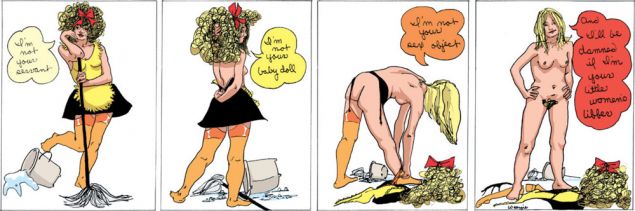

Detail from an untitled comic by Louise Simonson. In this literal ‘comic strip,’ Simonson creates an Everywoman character who challenges the male gaze by discarding the identities it has attempted to impose on her. Simonson is a comics writer and editor who has worked on major titles for DC and Marvel Comics, and has written comics-related books including “DC Comics Covergirls.”

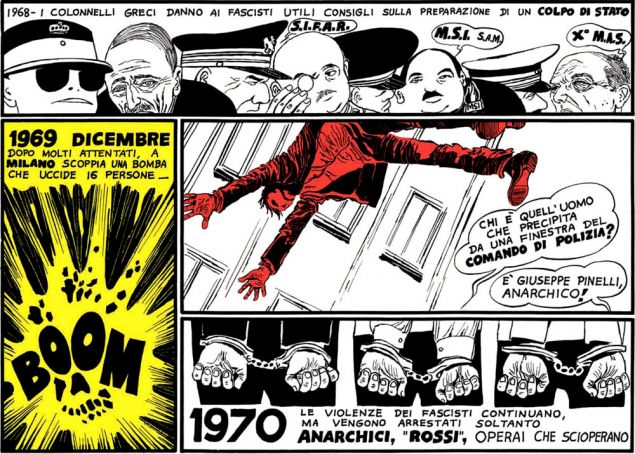

Detail from an untitled comic by Guido Crepax, which departs from the erotic “Valentina” comics for which Crepax was best-known, to present a thumbnail version of the struggles between Italian fascists, anarchists, socialists, and striking workers in the 1960s. In 1969, a bomb went off in Milan, killing 16 people; the falling man in the middle panel is Giuseppe Pinelli, who died after he fell (or jumped, or was pushed) from the fourth-floor window of a police station, where he had been taken for interrogation.

Detail from “Nothing to Shout About,” by Patrice Leconte, in which a character named Patrice Leconte asserts that nothing much happened in the 1960s. He compares the Buddhist monks who set themselves on fire to protest the mistreatment of Buddhists by South Vietnam’s Roman Catholic administration with Joan of Arc, and finds the former to be “chickenshit.” Mankind’s first step on the moon is compared, also unfavorably, with Columbus’ setting foot on American soil. Leconte is a writer, comic artist, screenwriter, and director; his film “Ridicule” was nominated for an Oscar for Best Foreign Film in 1997.

Detail from “The Spirit: The Soaring Sixties,” by Will Eisner. His character “The Spirit” was the focus of a superhero comic series with film noir overtones whose popularity had peaked by the early ’50s. In the Foreword to The Someday Funnies, Jeet Heer notes that at the time Eisner drew this comic, his “feet are still planted in the pulp tradition but he is already contemplating the more mature graphic novels that he would develop in the late 1970s and afterward.” Here, the Spirit’s attempts to work with computerized crime statistics are co-opted by the criminal element.

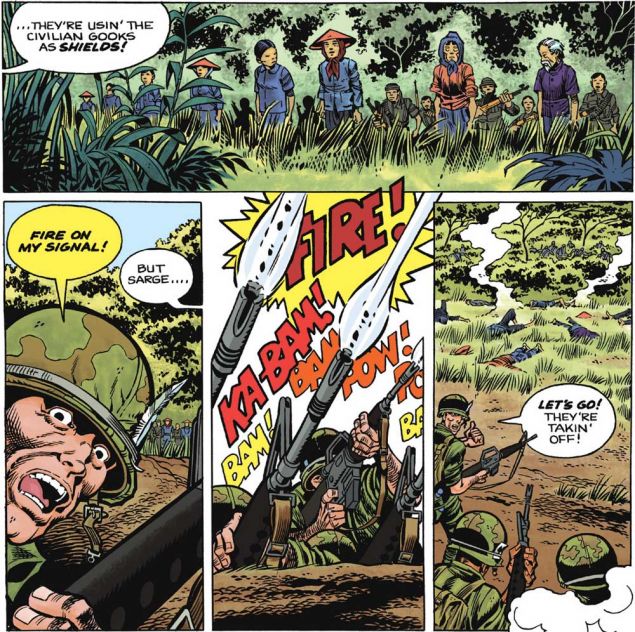

Detail from “Charlie!” by Herb Trimpe. In this comic, an artist drew the Hulk for more than 15 years, and was the first to draw the character Wolverine for publication, presents a horrific Vietnam War scenario. The use of the term “gooks” by one of the characters has echoes in the following artwork…

Detail from “Warlizards,” by Vaughn Bodé. The creator of the influential underground comic character “Cheech Wizard” contributes the adventures of two of his signature lizard characters at war in Vietnam. In this panel, we’re reminded that the term “gook,” like any name for The Other, can cut both ways.

Detail from “The Ballad of Beardsley Bullfeather or Tune In—Cop-Out and Drop-Up!” with text by Jack Kirby and art by Jack Kirby and Joe Sinnott. In a comic written in rhymed quadrameter, an admirer of Ayn Rand travels to the moon in a rocketship, where he “reads novels and sips cool martinis,” and ultimately disappears before the Apollo astronauts arrive. At the time, Jack Kirby was a pioneer of modern comics; with Joe Simon he created the Captain America character, and he worked with Stan Lee to create some of Marvel Comics’ signature superheroes. Joe Sinnott, one of marvel’s most in-demand inkers, worked with Kirby on The Fantastic Four in the late ’60s, and still inks the Sunday Spider-Man comic for King Features.