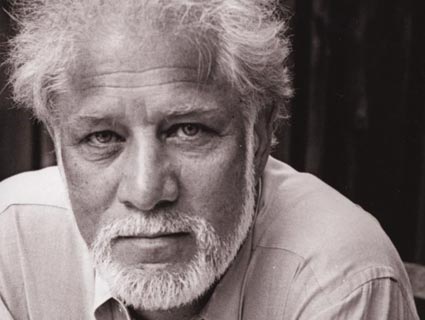

Photo: Shawn Grant

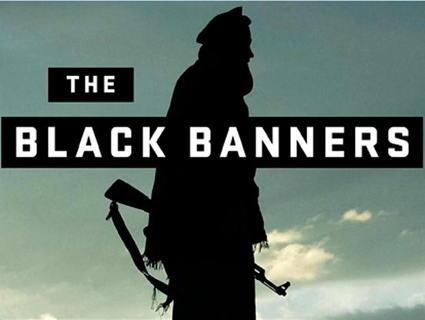

For his latest book, Chuck Palahniuk, best known for the 1996 cult classic Fight Club, researched the detritus of human existence to tackle death and damnation. Damned, out this week, is a darkly comic depiction of hell from the perspective of a 13-year-old girl who ends up in the underworld after overdosing on pot. In a Judy Blume-meets-Anton LaVey touch, Palahniuk introduces each chapter with: “Are you there, Satan? It’s me, Madison.” In his scab-and-toenail-clipping-laden underworld, wax lips are currency and The English Patient plays on an endless loop.

Palahniuk belies the fetishes of his fans with a placid, tidy, and unfailingly polite temperament. For a guy who can rap off disfiguring methods of masturbation, he’s remarkably grounded and introspective. On the eve of his book tour, I called the 49-year-old author at his home in Portland to talk about hell, inflatable dolls, and how zombie theology just might save us.

Mother Jones: You’ve referred to Damned as a “hideous novel.” Elaborate.

Chuck Palahniuk: I wrote it when I was taking care of my mother, who was being treated and eventually died of lung cancer. And so it was just the process and the circumstance of writing it was horrible.

MJ: You’ve spoken of fiction as a way for writers to work out their problems vicariously. So that was the case here?

CP: Right. My father had been killed in 1999. I was about to lose my mother. I think it’s a fantastic coping mechanism. It allows you to express all of your feelings through a different persona, to record and vent the feelings, like in a diary. And it allows you to allow time to pass.

MJ: Madison is a 13-year-old girl who ends up in hell, absurdly, after OD’ing on pot. What’s the parallel?

CP: Here I was, a middle-aged man mourning both of his parents, and that just didn’t seem to be a very funny book—a book that I wouldn’t find any kind of joy in writing. So instead of making it a middle-aged man, I made it a very young girl. And instead of her mourning her dead parents, she herself would be dead, so that she could mourn—miss her parents. I basically inverted the whole situation, which would allow me to express the same feelings in a comic way that denied the drama.

MJ: This book seems like kind of a nod to the young-adult section and Judy Blume novels.

CP: Yes. [Laughs.] There’s a classic form of story where an innocent character, an unknowing character, ends up in circumstances that he or she doesn’t understand, and they’re forced to just to make do. That’s kind of best typified by Are You There, God? It’s Me, Margaret, where the girl ends up moved to the suburbs from New York; or in The Shawshank Redemption, where the banker ends up convicted and in prison, and he doesn’t really understand the circumstances that got him there. Pollyanna—same thing. I wanted to write one of those sort of classic adaptation novels.

MJ: You don’t have children yourself. Did you do any research to inform your young protagonist?

CP: I did some very superficial reading about demonology and theology, things like that. And I did a lot of reading of the archetype, the innocent character thrust into a [new] situation. Beyond that, I really just kind of winged it—made it up.

MJ: So, what is hell? Other people?

CP: [Laughs.] It’s not other people; it’s physicality. Hell is composed of all the discarded aspects of our physical being: toenail clippings and loose hairs and blood and feces and urine and semen. For Madison, who is a presexual being really denying her physicality, hell is very confronting in that it’s nothing but the physical body present in all these discarded, disgusting ways. And that is based on, whenever I do book tours and I’m put in luxury hotels that have author’s suites, I’m always fascinated with seeing what books are on the shelves and how the autographs are dated. And knowing the chronology, I’m always fascinated with searching the room in a very thorough, forensic way, to look for the stray hairs and the mattress stains or toenail clippings or scabs—the physical evidence that people like Jane Fonda and Goldie Hawn and Maya Angelou, people who’ve slept in that room before me, were mortal beings.

MJ: Of all the movies that could be playing on an endless loop in hell, why did you choose The English Patient?

CP: I wanted a kind of lofty movie that a prepubescent girl would not really understand or appreciate. The Piano is also playing in hell. And also because, to tell the truth, sitting through both those movies was kind of a living hell for me. I just didn’t get [their acclaim]. So that part of Madison is definitely me.

MJ: There’s been talk of making a movie out of your novel Haunted, which has a Canterbury Tales structure—23 short stories, told by the characters.

CP: It’s funny you mention that, because I was just at the Netherlands Music Festival and I met with the director, a Belgian man named Koen Mortier whose big movie is called Ex Drummer. So there is progress.

MJ: One of the stories, “Guts,” is a meditation on hazardous masturbation methods. Will that make the cut?

MJ: One of the stories, “Guts,” is a meditation on hazardous masturbation methods. Will that make the cut?

CP: Oh, definitely. In fact, the “Guts” character is probably going to be the main protagonist and the narrator.

MJ: In Damned, there’s a rather bizarre sex scene involving a giant demon goddess and a severed head with a Mohawk. Where did that come from?

CP: Boy, that goes back forever. I remember being a child and reading the second book of Gulliver’s Travels, and being dumbfounded by the scenes in which the little tiny Gulliver is placed on the bodies of the women in this royal court. He is compelled to rove up and down the landscape of these enormous female bodies, and how disgusting he finds them. For a prepubescent child, that’s a really remarkable thing to read, because it is before you have an appreciation for carnal pleasure. These very fleshy, mortal scenes—they stayed with me for decades.

MJ: Any other classical influences hovering around you lately?

CP: Dante’s Divine Comedy. Damned is the first of three books that will follow Madison. The second book I’m working on now places Madison in purgatory, which is basically being stranded on Earth for a year. The third book will eventually get Madison to some form of salvation.

MJ: I guess every writer needs a trilogy.

CP: I’ve never done even two books that were linked like this. So three is a real challenge.

MJ: Your reading tours and fan-club following are sort of legendary. Do you have anything special planned this time around?

CP: I’m going to be reading a story called “Romance” that I wrote that came out in the August Playboy. Probably the most, kind of, romantic love story I’ve ever done. But it’s still upsetting. It’s funny and horrible. It’s being made into a short film right now. So that’s the reading part. Beyond that, I have the standard million inflatable things for people to fight over.

MJ: Like what?

CP: In the past, we’ve had blow-up sex dolls, inflatable four-foot penguins, inflatable Academy Awards last year, five-foot inflatable giant red hearts—severed arms and legs were big for a couple of years. It allows for physical participation, where people are clamoring so that I’ll fling something in their direction. And then competing among themselves to inflate these things in order to win prizes, which are typically books by other people that I really like, that I’ve shipped to the events. And then later, I can see the event infuse power into the larger world as people carry these large, unhidable souvenirs with them. And that part’s really fun. It’s kind of a low-budget piece of Christo art.

MJ: Beyond the cult following, there’s still a general perception that you are “the Fight Club guy.” Has your association with that story, and with the subsequent movie and actual fight clubs, been stifling, or liberating, or both?

CP: It’s liberating. Fight Club is what bought me my freedom. When you think about so many people—Burroughs, you think of Naked Lunch—so many people are just identified by one work. So it’s not so unusual. Ken Kesey, you think of Cuckoo’s Nest.

MJ: What else do you think is worth sharing these days?

CP: A couple of books I’ve just been in love with: One is a memoir that came out this spring called Chronology of Water by Lidia Yuknavitch. There’s a new novel by Donald Ray Pollock, called The Devil All The Time. Pollock had a book out, a collection of short stories, a couple years ago, called Knockemstiff, so this is his first novel.

MJ: That reminds me. You also put out an anthology of true stories, Stranger Than Fiction, a few years back. Is nonfiction something you want to revisit?

CP: I have a feature story in the November Playboy about going to the world’s largest—or the world’s first—zombie culture convention. I wanted to do a kind of Joan Didion version of what she had done with “Slouching Towards Bethlehem,” the landmark essay about being among the hippies in the Haight-Ashbury—but about being among these 20,000 fake zombies. It’s called “Slouching, Lurching, and Salivating Towards Bethlehem.”

MJ: Did the zombies break character to talk to you?

CP: What I found so fascinating about the convention is that it’s almost like a proto-theology. Like a Baptist national convention, where people were getting together and very passionately debating whether zombies could move fast or slow, whether they could feel affection. We’re seeing the beginnings of a religion. And it’s fun to watch people fight over the doctrines, or the catechisms, of what is gonna be taught as the right way of thinking of this kind of afterlife phenomenon. There were people who behaved as zombies, but they behaved according to a very strict dogma of what they though a zombie should be. So there really wasn’t any kind of single form of character.

MJ: For someone who studies social and cultural norms, and pushes that envelope in his writing, you seem pretty quiet when it comes to politics.

CP: Maybe it’s because my politics are kind of undecided. I grew up in such an atmosphere of conflict. Right now, it’s just a difficult time to be engaged in politics without being engaged in direct confrontation. In a way I’m still looking for that third option that’s going to unite people, not pit them against each other. Part of me has to wonder if some new form of religion isn’t going to do that. In a way, I’m looking to things like zombies that might present us with a new something, a new factor, that will allow us to transcend the right and left that we’re stuck with right now.