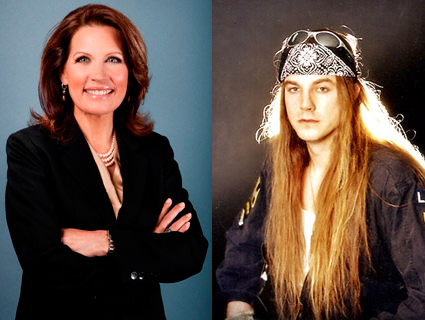

<a href="http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:%C2%A7Russo_Vito_%281946-1990%29_-_foto_di_Massimo_Consoli_28-VI-1989,_NY.jpg">Massimo Consoli</a>/Wikipedia

“Well, it’s about fuckin’ time!” This was the late playwright Doric Wilson’s reaction when he was approached by Michael Schiavi to be interviewed for The Celluloid Activist: The Life and Times of Vito Russo, just published by the University of Wisconsin Press last month.

A serious study of Russo’s life was long overdue. In 1981, he wrote The Celluloid Closet: Homosexuality in the Movies, a groundbreaking look at how Hollywood had long depicted gay characters as either sex-crazed predators or helpless victims. (It was later made into a documentary featuring stars such as Lily Tomlin and Tom Hanks.) He also co-founded ACT UP and the Gay and Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation; GLAAD now presents an annual award named after Russo (last year’s recipient was Ricky Martin).

Russo died in 1990 at the age of 44. I had known him for only four or five years, but I was referred to Schiavi by a mutual friend. I sent him an email with my reminiscences of Vito, which I’ve included below, slightly edited. Some of these episodes were expanded in Vito’s biography. (I thoroughly recommend that you read it!) Though this doesn’t begin to enumerate Vito’s accomplishments or his charms—and he had plenty of both— I’m presenting it here as a brief personal footnote to a very big public life.

• • •

Sadly, I didn’t know Vito for long. It was during a pretty intense time in all of our lives (for both those of us who made it through, and those who didn’t).

I met Vito at a dinner party at Howard Cruse and Ed Sedarbaum’s home in Queens. I went there with my partner John H. Wagenhauser. I’m not sure of the date; Vito had either just found out that he was HIV positive or had just gotten an AIDS diagnosis. (Schiavi’s book says that Vito received a diagnosis of Kaposi’s Sarcoma on August 13, 1985.) I remember him as being very energized about it, talking about everything he was learning, everything he was going to try, and was already trying. There was a lot of making it up as we went along in those days. My partner John was HIV positive and was going through a lot of the same stuff, so they were exchanging tips and encouragement on the latest drugs, herbs, and vitamins.

I think it was at that dinner that Vito announced that he was going to start screening films for friends at his home. (The book and film The Celluloid Closet had begun as a series of movies that Vito would show with commentary to the Gay Activist Alliance starting in 1971; the screenings at home were a return to his role as a film impresario.) It turned out that I lived a block away from his apartment in Chelsea, and he invited John and me to attend. He had this tiny little apartment, with a small film projector as well as a VCR, and would show a collection of short and long films. It would get quite crowded; there would sometimes be as many as five people on his couch alone, and I remember one young couple, newly in love, pretty much making out on my lap through an entire movie.

Alice Roberts as the Countess Geschwitz with Louise Brooks in G.W. Pabst’s Pandora’s Box (1929).I remember seeing Caged, Next Stop Greenwich Village, Parting Glances, Pandora’s Box, and other commercial releases, as well as films of Bette Midler performing at the Continental Baths. I’d heard a story that Midler had lost her copy of those films, and looked at Vito’s copies as preparation for doing her film The Rose. There was another film of Midler at the 1973 Gay Pride March, where she performed to ease some tensions that had occurred between some of the drag queens onstage and some of the lesbians in the audience. He also had a short film, Beauties Without a Cause, which I would, tiresomely, always request; and he indulged me with it on several evenings. Some evenings were potlucks; I remember bringing a salad once, and then realizing that Vito couldn’t eat it, because uncooked vegetables were thought to be very dangerous for people with compromised immune systems.

Alice Roberts as the Countess Geschwitz with Louise Brooks in G.W. Pabst’s Pandora’s Box (1929).I remember seeing Caged, Next Stop Greenwich Village, Parting Glances, Pandora’s Box, and other commercial releases, as well as films of Bette Midler performing at the Continental Baths. I’d heard a story that Midler had lost her copy of those films, and looked at Vito’s copies as preparation for doing her film The Rose. There was another film of Midler at the 1973 Gay Pride March, where she performed to ease some tensions that had occurred between some of the drag queens onstage and some of the lesbians in the audience. He also had a short film, Beauties Without a Cause, which I would, tiresomely, always request; and he indulged me with it on several evenings. Some evenings were potlucks; I remember bringing a salad once, and then realizing that Vito couldn’t eat it, because uncooked vegetables were thought to be very dangerous for people with compromised immune systems.

Vito got to know my partner, John, pretty well. We were all active in ACT UP but John went to a lot more of the out-of-town actions than I did, and spent time with Vito at those. (John died of complications due to HIV in 1992.)

I remember going to a group reading at the Gay and Lesbian Center in New York, in which Vito was participating: I think he read an essay called “We Must March, My Darlings” (titled, I assume, after the line in the Walt Whitman poem, not the Diana Trilling book), about how the Gay and Lesbian March, while a bit mainstream (little did we know!) was still important. I was walking up the stairs and came across Vito, huffing and puffing mightily. This was near the end of his life, I think, and I was shocked that he was even attempting the stairs, alone or otherwise. He just looked at me and said, “They didn’t say that this was gonna be upstairs!” Having the nearest available shoulder to lean on, I offered it, and somehow—he was pretty weak and had trouble breathing—made it to the room where the reading was.

At this point, his friends put together a list of people who would help Vito with things; I would occasionally get called to pick up or drop off his laundry at the place around the corner, or pick up some Advil or Tylenol (one of the two he absolutely couldn’t take; I forget which) at the corner deli, Corky’s, which was on the ground floor of my building.

I didn’t see him when he went into the hospital. At this point there were a lot of closer friends helping him, and I got the feeling that having to be social would tire him out.

I attended Vito’s memorial service at Cooper Union’s Great Hall, where Larry Kramer gave his “You Killed Vito Russo” speech (Schiavi notes that the published version is called “We Killed Vito Russo”; I’m one of those who remembers him saying “You”) with Vito’s family and many of his caregivers in attendance. Larry was trying to make the point, in his usual in-your-face way, that no one, not even the gay community and their friends and supporters, had done enough to force the government to work to end the AIDS epidemic. I was fairly appalled by Larry’s speech, but not too surprised. I have a feeling that Vito would have rolled his eyes, but then given his grudging approval of the political gesture.

Somewhere I’ve saved one of those old mini-cassette answering machine tapes with Vito’s voice on it. Even if I found it, I don’t have anything which would play it now. I remember that he called me “sweetie” on the tape. He called everybody “sweetie,” and it meant something every time he said it.