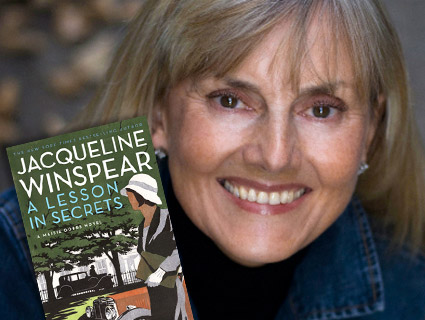

Photo of Jacqueline Winspear by Stephanie Mohan

Listen to an audio version of this interview.

Jacqueline Winspear is the author of the bestselling Maisie Dobbs historical fiction series. Although the Dobbs mysteries are set in England during and after World War I, the books address many military issues relevant today. The latest novel in the series, “A Lesson in Secrets,” was released in May. Winspear spoke with Mother Jones recently about PTSD, shrapnel, and the importance of knowing how to start up a 1920s roadster.

Mother Jones: The character Francesca Thomas, in “A Lesson in Secrets,” says to Maisie, at the end of the book, “We both understand that the war of words, of economics, and of underhand economic activity goes on. The front line is still there, though the trenches look a little different.” She also quotes the character Greville as saying, “We do not pay enough attention to the past, and that one of his fears was that in 1914 we had become a reflection of history when we embarked upon what would be considered another European Thirty Years War.”

Jacqueline Winspear: Yes.

MJ: Yet the books also seem to speak to very current issues on the waging of wars: PTSD, espionage, ethical grey areas, the economic motivation behind warfare, wasted life, the individual human and social costs, and the dissolution of an empire. Given that, do you think that there are important differences between the two World Wars, and war as it’s fought in the 21st Century?

JW: Well, you know, of course there were some key differences between the two world wars. The First World War was the Great War, as it’s known; there were so many components of that war. We talk about globalization today as if it’s some great big new thing, that we’ve all just discovered. But there’s really nothing new about it. It was Niall Ferguson the historian who said that the Great War ended the first great age of globalization. Now, there were all these trading agreements prior to that war, which, if you looked at the small print, also included a commitment to go to the aid of in the time of war. So what happened was, that almost as soon as the tragedy in Sarajevo happened, and then you had Austria moving here and you had all sorts of things sort of starting to come down… I mean, Europe came down like a pack of cards. And I think it was H. G. Wells who said that you could… everyone could see what was happening, but no one knew what to do to stop it.

And I don’t think you can say that about the Second World War; there was a dictator, a ruthless dictator, or this was how it was seen, who had to be taken down. But if you look at that history again, it goes back to the Great War; and particularly, disenfranchisement of Germany, as a result of what went on during the Paris Peace Conference. And so in a way, you could look at it and say, well this is yet another Thirty Years War; but the two wars did very much have their differences.

MJ: And what would you say is the difference between those wars and the wars that are being fought now; are there general differences?

JW: You know, I think there are always differences in terms of why wars start. But you know, it’s a funny thing. I’m a storyteller; that is what I do. And I’m particularly interested in history; and in history of a certain era. But what is interesting for me is how many, how many things you see repeated.

I often think it would be really interesting to take all of those who would wage war to the battlefield cemeteries, and say, explain yourself to the dead. Explain yourself to the dead! I think it was Harry Patch, who was the last living World War I veteran; and by veteran I mean someone who actually fought in the war, he didn’t just happen to be in the army at that time, in the Great War. And when the Iraq War started, he was interviewed, and they said, well what do you think of this? And he said, in a very sad voice, “Well, that’s why my mates died. We thought we were going to end all that sort of thing.”

But going back to the essence of your question, as with any war, there are so many, dare I say it, interested parties. There was actually an officer in the US Marines who had been through several wars before going to the Western Front in 1917; and who I think ended up resigning his position. He said, ‘wars are all about money, and I’m sick of it. I’m sick of being part of this, this striving for more money, for more power.’ And I think that one of the things that we all ask ourselves, whoever we are, is: who stands to make a lot of money out of this? And, certainly, it comes back to people like armaments makers, and so on and so forth. If you look at the First World War, the Kaiser was actually, actively buying a lot of the armaments from Britain! in the years, in the run-up to the First World War. And I mean, there was a connection there. He was, indeed, Queen Victoria’s grandson. You know, they were all related, all these royal families.

But you know, I think, I think we can… in truth, what does anyone really know about the impetus to go to war? And so much is uncovered in hindsight. And there are aspects of even past wars that are only coming out now. Historians discover letters here, notes there, and look very carefully at different aspects of not only any conflict but any great historical event.

MJ: That happens in your books; Maisie and her fellow countrymen go through periods of finding out things about the War; even just after the War, that they didn’t know at the time.

JW: Yes, indeed. As I’ve said, I am a storyteller, and it just so happens that history is the geography that I deal with. When we read about past wars, there is a finite time. There is the Great War, from 1914 to 1918. There’s the Second World War, which, if you’re a European is 1939, 38 or 39 to about 1945; in this country generally thought of as 1941 to 1945. They’re all finite dates; but the truth is, that war’s not like that. It bleeds out from the edges. Take my grandfather as an example. He died at the age of 77. I was a child when he passed away, but on the day he died, he was still removing shrapnel from his legs. Shards of shrapnel from his legs, from wounds he’d received in the Battle of the Somme in 1916. And just that, to me, is a metaphor for war. That we’re still removing the shrapnel from our collective memory, our collective experience, years later.

In a way it’s a time bomb, which we don’t realize that we have. It’s so easy to miss. And if you think of the Great War, which is the war that has, thus far, been at the root of many of my stories, there were 750,000 men in Britain killed or thereabouts; but, there’s about 1.5 million severely wounded; and according to official records, 80,000 severely or profoundly shell-shocked. It’s probably closer to a quarter of a million men. But you could say that no one that goes into a field of conflict, man or woman, is ever psychologically the same again. And those journeys can be the stuff of story. Easily.

MJ: Maisie is going through that journey, personally.

JW: Absolutely.

MJ: I’ve been getting the feeling, and especially so in this last book, that Maisie’s life, and her values, are becoming more complicated and conflicted.

JW: Yes.

MJ: Which may just be part of growing up (both laugh). I also got the feeling in this current book more than in any of the others that you were developing characters, one that jumped out at me was Delphine Lang, that I like to think of as the Kung Fu Nazi…

JW: Right, definitely! The Kung Fu Nazi! That’s a good one, I like it!

MJ: …and setting up conflicts for future books. Is there a Grand Plan for this series?

JW: For me it’s incredibly, it’s a very compelling challenge to take this woman, who is very much a woman of her generation, who has come from lowly beginnings; who has had an extraordinary opportunity, admittedly; not unheard-of, but extraordinary all the same. And given up an educational opportunity to go to war. And with that behind her, of course she has also an incredibly interesting mentor, and has an opportunity to work with that mentor as an investigator. So taking that person, with this background, with a certain set of sensibilities and very strong values: who is she as she moves through time?

And for example in the book I’m writing at the moment (and this is not giving any great game away) it’s right at the beginning of 1933. Adolph Hitler is Chancellor; has come to, if you will, the throne. But at the same time, one of the biggest controversies in the newspapers was about a certain type of bowling used by the British cricket team, which was thought very unsportsmanlike, in the test matches against Australia. And it was called ‘body line bowling,’ because it actually went straight for the body, and you could seriously injure a person. That to me is fascinating, that amid the big things that happen in the world, you know, most of the papers are obsessed with the wedding between two people [Prince William and Catherine Middleton] who have lived together for the last 8 years, because one of them happens to be Royal. So that’s what’s interesting to me, moving someone through time; in a way, history is part of my landscape. And it fascinates me that history can be so easily reflected in what happens today. (laughs) Does that make sense?

MJ: Oh, definitely, yes. And I love the point about the change in the rules in bowling; that seemed like such a metaphor for the change in the rules of warfare, that happened in the Great War.

JW: Well you know, the interesting thing is… as Churchill said about the Great War, and he said this in about 1924, that it was the first war in which man realized that he could obliterate himself completely. If you consider the way the whole world was impacted, 18 million people worldwide died, and that is taking into account military and civilian deaths: 18 million people. And it was the whole world, if you will. You know, many of those trenches were dug by Chinese. There are photographs of Chinese looking like they just came from China, with their hats and so on, digging the trenches, right from the beginning.

One of the things that was interesting in that war was actually the way that even then, there was ignorance of history. Because when the generals… and I’m not a big one for dates and generals, I’m really, really very interested in social history rather than very specific military history; but the two do, you know, they do cross paths, obviously. At the outset of that war, the generals in Britain tended to look at the most recent war, to say, this is how this war is going to be fought. And their most recent war of any note was in fact the Boer War, which was a war of great cavalry charges; (and actually the first concentration camps were there.) Where what they might have done, and would have been better served by doing, was to look at the American Civil War, which was where you saw trench warfare really come into its own. Because trench warfare was of course the great horror of the Great War.

MJ: Maisie also is getting involved in the espionage industry that was going on between the two wars. But her propensity for finding the truth whatever it is almost guarantees that her investigation won’t be that limited in scope.

JW: That’s correct. One of the things that truly happened at that time was that there was a great interest on the part of the Security Services in Bolshevism. But to some extent, the whole aspect of Fascism was a real hot potato. Because so many of the aristocracy were enamored of the tenets of not only fascism but also of Adolf Hitler himself. And you know, that was treading on a lot of toes. So it was an interesting conundrum to put the character in.

MJ: What do you think about the conflicts between the personal and professional life of someone involved in espionage?

JW: You know, I don’t know too many people who have done it. Although actually I have met a few! One has read about people who have passed away, and then you hear that their family has found out that they worked in espionage during the war. In fact, let me give you an example. This was something that I pulled out of a British newspaper about 10 days ago. It was an incredible story about a top female MI5 spy, and her story emerged after her death. She played an absolutely crucial role in the success of the D-Day landing, but her secret had remained so for over 50 years. She was a grandmother of seven. Died at age 89; and it was only after she died that anyone who knew her knew what she was up to in the war. And that to me, gives a hint of that personality. You know: this is my job, this how I do it; but you know what, I’ve got this other life.

MJ: You talked in your 2005 bookreporter.com interview about being interested in the details of how ordinary people live. It reminded me that Erica Jong, in the afterword to her novel “Fanny,” says that the professor under whom she studied 18th Century literature at Barnard believed that you couldn’t understand the 18th Century in England without understanding, quote, “the condition of the plumbing, the emptying of chamber pots and cesspits, the lighting of the streets, the various schemes for reducing muggings and street crimes.”

JW: Yes!

MJ: And that’s something that’s always struck me about the Maisie books is how rich it is, and how important ‘the way things are done here’ are.

JW: It’s really important in any historical fiction, I think, to anchor the story in its time. And you do that by weaving in those details, by, believe it or not, by the plumbing. I’m one of those people… when I was a kid, and you know, “Britain, great home Britain,” there’s stately homes everywhere, I remember going with my parents to visit some castle or other; and the first question I had was, ‘So, how do they go to the lavatory?’ How did they do that in those days? And in fact it was really great to learn that. Not that I’ve mentioned that specifically in Maisie Dobbs; but here’s an example. It was in the first book, she has use of a car which eventually becomes her own. Now, in one scene I wanted her to get in the car and drive up the road. And luckily I found out, because I’m curious about these things, how you started this car. Because, we assume, these days, you just get in a car, you turn the key, and woosh, you’re up the road. Or even now, dare I say, you don’t turn a key; you get in a car and you’re up the road. And yet with this particular car, it was a five-step process to start it. So how do I let the reader know that? Without saying, well first you lift the bonnet, because it’s called a bonnet in Britain. And then, you know, you turn on the fuel pump, and then you do this with the magneto, and then you do that; and then finally you get in the car and you do this. Instead I made it into a conversation between a chauffeur and Maisie. There was a conversation; he talked to her about it. So with some of these old movies, where they leap into the car and have a quick getaway, you know, not on your Nelly! It’s not gonna happen!

Also the clothing, people often ask why I talk about what characters are wearing. And that’s really important to me, because you have to have a picture of how people moved in their clothes. So what we learn about Maisie is that actually she’s quite parsimonious in many ways. And that she will wear, not only a dress that’s several years old, but she’ll wear it with a coat that’s even older. Or something that she’s pulled out that’s new or that’s being given to her. There was a movie that came out a few years ago, a more contemporary movie set in the 60s, called The Bank Job. It was actually very good. But one of the excellent comments about that movie was that the clothes, the costumes, the clothes that people wore in the movie weren’t the latest fashions. Because people actually don’t wear the latest fashions all the time. If you look at some historical movies, and read historical fiction, you would think that everybody wore the latest fashions every day of the week. I don’t know about you, but I wear clothes until they’re years old. That tells you something about not only the time, but the character. Also in terms of construction, for example. One of the interesting aspects of social life between the wars, to me, is that even at a time of depression, when Britain didn’t have a lot of money, housebuilding was just going through the roof. And there was a certain style of housebuilding [about which some people were] very disrespectful, like, Oh my God, the Masses are moving into their fake Tudor homes, and things like that. And there were all these special deals, and big posters; this was in the late 20s. And that was really when what they called Metroland was born, with those big housing developments that you often see, particularly as you’re coming in to land at Heathrow airport. All that absolutely supports the comment by Erica Jong’s professor: that you have to know how everything works. It gives texture to your story.

MJ: It certainly does to these stories. And as you were saying about the outfits: I mean, some of Maisie’s outfits are minor characters, which recur.

JW: Yes!