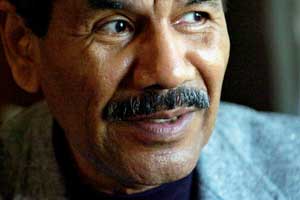

Photo: Mark Saltz/AP

Journalism helped reform Wilbert Rideau—and in turn, he used it to reform one of the country’s toughest prisons. In 1961, the 19-year-old Rideau was sentenced to death for killing a woman during a bungled bank robbery in Lake Charles, Louisiana. Sent to Angola state penitentiary, he underwent a profound transformation. After his sentence was commuted to life, he became editor of the prison magazine, the Angolite, turning it into a respected publication that exposed abuses by guards and inmates alike and was nominated for seven National Magazine Awards. He became a correspondent for NPR’s Fresh Air and codirected the Oscar-nominated documentary The Farm. Several wardens vouched for his complete rehabilitation, yet a mix of racial politics and tough-on-crime posturing blocked his release for more than three decades. Finally, his case was reopened, and in early 2005 he was found guilty of manslaughter and let go with time served. Rideau is the author of a new memoir, In the Place of Justice: A Story of Punishment and Deliverance. He spoke from his home in Baton Rouge, joined by his wife, Linda LaBranche.

Mother Jones: You’ve been out of prison for a little over five years. I’m curious: What’s been most surprising about being out?

Wilbert Rideau: You hear all these horror stories from other ex-cons, and I figured people are gonna dump on you and whatnot. But you know, largely people treated me respectfully. People were helpful, and I was pretty surprised—I mean, I’m sure that everyone didn’t see me that way or, you know, everybody didn’t feel kindly toward me, but it’s to their credit that they kept it to themselves. I was really surprised by that. I was also surprised by the amount of—not in relation to me—the incivility out here. In prison it’s not as uncivil because everybody plays for keeps. So you’re kind of careful about what you say to others and how you treat others.

It’s not like prison. In prison, everything is there within reach because it’s an isolated, self-contained community. If you want your shirt cleaned, there’s a laundry. If you want to eat, there’s a dining room. Whatever you want, you can make things happen. Not out here. If you want your shirt cleaned, you either got to wash it and press it yourself or get in your car and drive down to a cleaner’s. Prison is all sort of planned out, and you can pretty much predict what you’re going to be doing five years from now. But out here’s it’s totally different, totally a different ballgame. You can have the best-laid plans—and then your car doesn’t start. Those are the things you don’t think about when you’re fantasizing about freedom.

MJ: Do you have any habits or routines you developed in prison you find yourself falling back on?

WR: Not so much falling back on—kind of hard to shake. The questioning of motives, you don’t accept things at face value, always questioning why—that’s a prison thing. It serves you well because it’s kind of protective, but that’s a remnant from prison. I used to always want to sit with my back to the wall, but I’ve lost that. I no longer do that; in fact, I just get a chair just like anyone else. I still tend to over-explain myself—that’s something you pick up in prison because you always have to justify what you do and explain what you want.

MJ: What are some misconceptions people on the outside have about prison?

WR: Boy, where do I begin? Number one is that prison is a hellhole where people are subjected to unmitigated violence. This is all a part of the movies. Most of the perception that’s been created about prison comes from movies, because violence and cruelty draw audiences. It also comes from the people who perpetuate this myth that it’s a horrific place. Prison reformers—let’s face it—they had to come up with some of the most shocking stuff in order to get the public to want to do something to try to reform this place. Penal administrators, they want you to believe that everybody in prison is violent and evil because that’s necessary to justify the endless expense of the system. So they’ve demonized prison to the point where it’s just a hellish place. And that’s not the way the majority of prisoners in America live. Of course, they don’t live in country clubs. That’s not prison, either.

What most people don’t realize is that violence in prison is very targeted. Except for sexual violence and strong-arming, violence in prison is very targeted. It’s not random. It has to do with you and how you behave. The general perception is, you walk into prison and you’re an automatic target for violence. That’s not the way it works. There are ways to minimize it. You have to be strong in your resolve. You have to want to do good and do right. If you’re going in there to be a gangbanger, well, yes, you’re gonna be caught up in a whirlwind of violence. Most prisoners go in trying to do their time, trying to get out of prison. And that’s all they’re about. In fact, I was in the bloodiest prison in the nation and in 44 years I never had a single fistfight. And when I walked out of prison, I was probably the single most influential person in the joint. That should tell you a lot about violence. When I went in I was a real skinny guy. I forget how much I weighed—Linda, from the records?

Linda LaBranche: 115.

WR: Yeah, I was skinny guy. They used to kid me about having to hold onto the railing when we were going to chow because the wind might blow me away [laughs].

MJ: You went in with an eighth-grade education, and now you write like you went to grad school. How did you learn how to write?

WR: One day I was sitting on death row, and I wanted to leave something behind that would contribute to furthering a better understanding of the criminal, and the only way to do it is to write it. I didn’t have any other forums, so I had to teach myself to write. I concluded that the books I was reading were written by people who didn’t come into the world writing with a pen in their hand, so that means they learned it. And if they can learn it, I can learn it. So I started reading books differently. Then I started reading books, newspapers, whatever. I began reading then as much for style and how they string their worlds together, how they present their thoughts as much as for content. Gradually, I learned. For a long time, and occasionally even now, there are words I’ll come up with and I’ll mispronounce ’em because I learned just from reading. It wasn’t until we got a TV that you could learn how the words were actually pronounced.

MJ: How did you join the Angolite?

WR: When I got off death row, I wanted to join the Angolite staff because I felt it was a pretty easy job. The majority of the people in the place were working picking cotton in the fields. I didn’t want to do that. At the time, the Angolite was the equivalent of a boarding school newsletter and staffed completely by white guys. Everything was censored. The exception was one window in time, when I got on the Angolite and struck an understanding with [former warden] C. Paul Phelps. He had the idea that a free inmate press might make a difference. [The administration’s] whole attitude was that they didn’t have anything to hide. They felt that the more that society knew about what was going on, the better everybody would be. That was a philosophy that prevailed in the Louisiana state pen for two decades from warden to warden. Even wardens who were bitter political enemies, they all believed in the same philosophy. That went on for two decades. Man, that was unique in America. And you know, it’s still unique.

MJ: Does it affect what you write when you know the warden or a prisoner can come to you and tell you what they think about it?

WR: The first thing I realized was that the prisoners no more wanted “tell it like it is” than the guards. You had to tread lightly in the beginning, but gradually the concept took root and they began to appreciate it. The thing is, you have to try and treat both sides the same way. You have to be fair to both sides. The guards realized that, hey, I call the shots on the inmates, just like I call the shots on them. When they’re doing right, I say they’re doing right; when they’re doing wrong, I say they’re doing wrong. That is acceptable to them. As long as they feel everyone is being handled the same way, equitably and fair.

MJ: You wrote this giant story on sexual slavery in the prison in the mid-1970s. Did prisoners react positively to it because they knew you were also doing big exposés on the guards?

WR: Well, some of them didn’t because they thought, “Hey man, you’re putting our business in the streets!” But then, a lot of corrections people felt the same way, too. You can’t please everybody. It doesn’t matter what you write; somebody will be offended by it. But once you acquire a reputation for fairness, for impartiality, and knowing what you’re talking about, and you always try to be right, people will respect that. Even the guys in prison who don’t like it. I wasn’t worried about the people who can think—I was worried about the crazies. One time I got a letter to the editor from a guy who was in the mental cell block. He was holding me responsible because they kept serving a particular kind of cornflakes every morning. I remember a warden, Warden Whitley, telling me, “You have to worry about the same things I worry about. You know, people blame me for things I have absolutely no control over, too.”

MJ: What’s happened to the Angolite since you left?

WR: While I was still there, they were clamping down on it. If you pick up the magazine now, there’s no controversy, there’s no criticism of the administration or anything that’s going on in the prison. There’s a whole lot about sports and religion. They’ll write about issues, but not about practices. Mostly it’s about religion. If you go by what you read and what you hear, Angola probably has the largest congregation of Christian prisoners in the world. I know prisoners. And prisoners, as a rule, when they’re out of prison are the most irreligious group of people in the world. So, when you tell me 70 percent of the prison population up at Angola are supposed to be Christian now because of this administrative push to turn the prison into a church house, I’ve got some questions! [laughs] That’s not to say there aren’t some religious prisoners. But the majority have never been, and whenever they get religion, it’s usually as a means to an end. It’s kind of a con job.

MJ: When your death sentence was commuted to life, at that time if you were serving a life sentence in Louisiana, generally it was understood that you could be paroled after 10 years and 6 months. You never hear about that kind of thing happening anymore. And yet people like to talk about the good old days of law and order.

WR: It wasn’t just Louisiana. Almost all over the country back then, people believed in rehabilitating people. Or put it another way: Teach the criminals a lesson, and once they’ve learned their lesson, then you parole them and let ’em back out to become taxpaying citizens. They also believed in giving people a second chance. That was the foundation this country was built on. Everyone believed that a person deserved a second chance, but over the years, they’ve thrown that out the window.

LL: At the time that I became involved in Wilbert’s case, I learned that the average time served on a murder sentence in 1986 or ’87 was 7.6 years nationwide.

WR: She did research on all that. That changed the whole debate on me. It was always a case of “does he deserve…” or “should we give him clemency?” but then it became an issue of fairness.

MJ: Is there anyone who is beyond rehabilitation or beyond redemption?

WR: I don’t know about that. If you’re gonna judge people by crimes, you get into a quagmire. If you’re gonna judge people by themselves, by who and what they are, that’s a different ballgame. The thing I’ve learned in life is that basically good people can do some really horrific things, and basically bad people can do some really good things. Life isn’t that simple. Everybody has a dual potential to do good and bad and you’re capable of doing both. But as to whether someone is beyond redemption—I have run across some individuals like that—they’re dangerous. But most of the people I met and served time with, they want to be better than who they were. They want a second chance in life. Now, the policy is to simply bury everybody in prison, and that’s supposed to somehow solve the crime problem. But if that was the case, Louisiana, which has your highest lockup rate in the country, should be crime-free.

But no, there’s no connection between the two. When you bury everybody in prison you buy a lot of real estate. Every time you send somebody to prison for a very long time, that’s real estate, and we are a society that’s not blessed with inexhaustible resources. Everyone’s crying about the cost now. Even in Louisiana, they’re doing just like in California. They don’t want to do anything about prison because prison has become an industry. It’s an entrenched industry with special interests involved. I don’t know if you’ll ever be able to reform it anymore. Look, there’s no society that can function without law and order. I’ll be the first to acknowledge that, but you don’t need all of this industry that they’ve built on the back of that need.

MJ: You had the support of former wardens and parole board members, yet no governor would approve your release—why?

WR: Because they made me a political football. And whenever that happens, it’s difficult for any prisoner to get out. What really made me high-profile is that I started doing good things. I guess in a lot of ways I was novel. I used to often liken myself to a dog playing a piano, because here I am, I’m a prisoner and I’m doing all this journalism, I’m an editor. I wasn’t being censored. No other prisoner in America was able to do the same thing.

MJ: Do you ever think that if you’d kept your head down you would have gotten out sooner?

WR: No. Because that wouldn’t have happened. The only reason I got the help that I got was because I was high-profile and I won awards. Otherwise, I would have been just like a lot of other guys: alone, trying to deal with the system.

MJ: You write about how when prisoners lose hope, that really becomes a factor in their behavior and their potential for violence. I was doing some reporting on prison riots and prison violence last year and no one ever mentioned that as a factor. They talked about overcrowding or administration, but no one ever talked about whether prisoners feel a sense of hope. How do you give prisoners a sense of hope without misleading them?

WR: The reason why the people you talked to didn’t bring up the subject of hope is because it has to do with expectations. Back then in Angola, all of those guys expected to be released at some point. Today it’s a different ballgame. When people go to prison with 20 to life with no parole, they don’t have those same expectations. But hope springs eternal. There’s always a chance. Whereas before they used to have hope for clemency or hope for parole, now they have what they call “writ hope.” They hope that they might be able to somehow or other get something in court. They know it’s rare, because the courts have become just as harsh as the parole boards. But every now and then—hey, I’m one! I guess I’m a perfect example of that. Forty-four years, and finally I managed to get out.