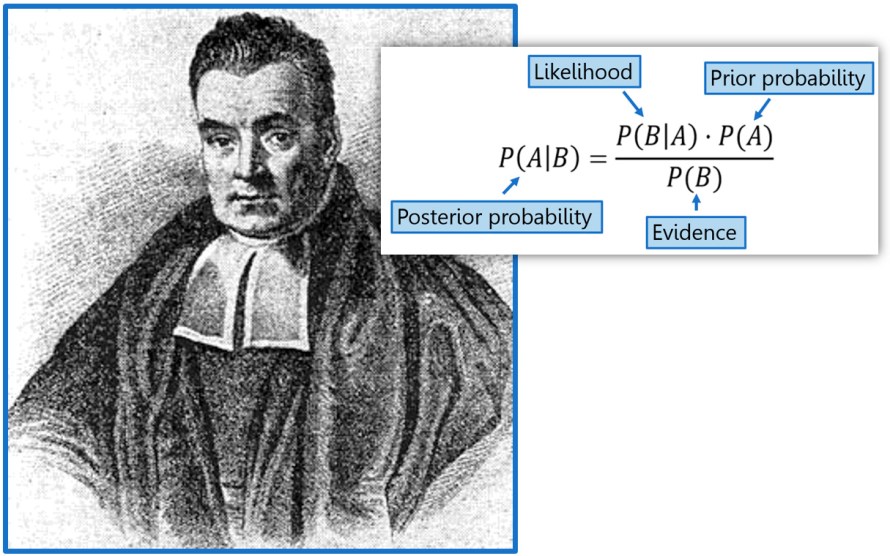

The Rev. Thomas Bayes, whose simple and fairly narrow formula eventually inspired a vast new field of statistics.

It is really, really hard to find stuff to write about other than the C19 pandemic. So instead, how about a complicated post about Bayesian statistics? The underlying study that prompted this post is, unfortunately, about coronavirus testing, but it’s really about Bayesian statistics. Honest.

Bad news first: most of you probably don’t know what Bayesian statistics is, and it would take way too long to explain properly. I’m not even sure I could do a fair job of it, actually, so just skip this whole post if it’s not your thing. OTOH, if you’re really bored, go ahead and read it and then use the internet machine to enlighten yourself about the whole subject.

The whole thing starts with that Santa Clara study of C19 antibody testing. The authors concluded that the infection rate of the entire population was between 2.5 percent and 4.2 percent, which includes even those who had no symptoms and never knew they were infected. Unfortunately, the antibody test had a false positive rate of 1.5 percent, which means that the true range of the infection rate was about 0 to 5 percent.

So were the authors justified in using their narrower range of 2.5 to 4.2 percent? The loud and clear voice of the statistics community was no. But today, Andrew Gelman, who was quite critical of the study, writes this:

It seems clear to me that the authors of that study had reasons for believing their claims, even before the data came in. They viewed their study as confirmation of their existing beliefs. They had good reasons, from their perspective.

….It’s a Bayesian thing. Part of Bayesian reasoning is to think like a Bayesian; another part is to assess other people’s conclusions as if they are Bayesians and use this to deduce their priors. I’m not saying that other researchers are Bayesian—indeed I’m not always so Bayesian myself—rather, I’m arguing that looking at inferences from this implicit Bayesian perspective can be helpful, in the same way that economists can look at people’s decisions and deduce their implicit utilities.

This has always been my big problem with Bayesian statistics and Gelman makes it very clear in this post. Bayesiansim requires you to start with “prior beliefs” as part of the methodology. That can be a “flat prior,” in which you assume nothing, but then you end up with little more than you’d get from ordinary frequentist statistics. On the other hand, if you assume a meaningful prior, it means that your results can be stretched into almost anything you want. You can simply explain, in whatever detail you want, that “previous studies have shown X,” and when you plug that in as your prior you get a new result of X ± Δ.

But as Gelman acknowledges, this makes “prior” just a nicer word for “bias.” That’s not a very good selling point. At the same time, without priors it’s not clear to me how useful Bayesian statistics is in the first place. For now, then, I remain confused.