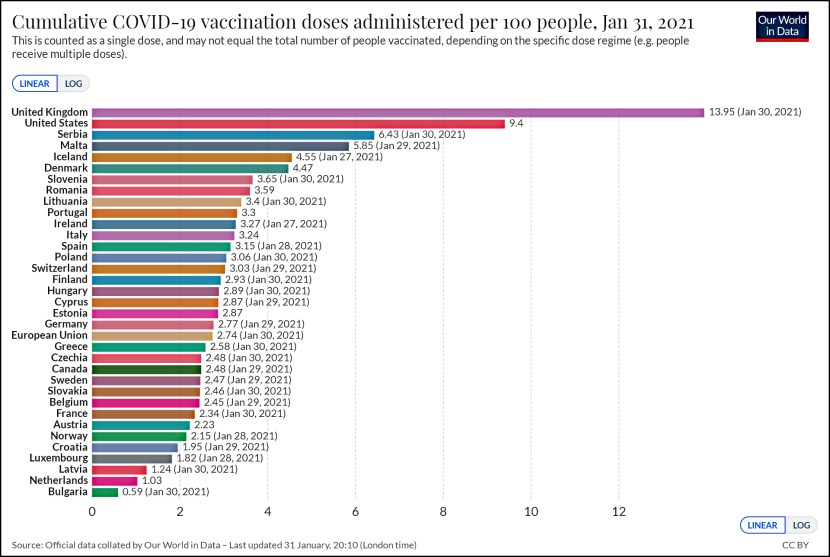

What’s really behind the skyrocketing problem of opioid addiction? The obvious culprit is the fact that in the early 90s doctors began prescribing opioid painkillers like Percocet and Oxycontin at much higher rates:

This chart seems pretty conclusive, but if you dive a little deeper things get more complicated. The main reason prescriptions went up is that doctors really had been undertreating pain for a long time. And it turns out that the biggest problem with high rates of opioid prescription don’t come from pain patients anyway. Addiction rates among pain patients are actually fairly low: anywhere from 0.1 percent to less than 8 percent, and very few pain patients ever move on to heroin or other drugs. Rather, the biggest part of the problem comes from people who score opioid painkillers elsewhere. And where do they get them? From leftovers sitting around their parents’ medicine chests. From friends. From the black market.

In other words, if we really want to address the opioid epidemic, our best strategy is not to focus all our attention on prescriptions among legitimate pain patients. Nor is it to refight the war on drugs yet again. Instead, we need to:

- Get better at screening people with previous (or current) addictions.

- Prescribe fewer pills after surgeries, but make it easy to get refills. The idea here is to limit the number of leftover pills lying around, but to do it without making things difficult for pain patients.

- Crack down on pill mills and on shipments plainly bound for the black market—but without making doctors live in fear of the DEA knocking on their door if they treat their pain patients properly.

- Get tougher on misleading pharmaceutical marketing.

- Fund much more research on pain management and alternative pain strategies.

This is what President Trump ought to be doing as part of his “public health emergency” over opioid deaths.