Britain's Labour Party leader Ed Miliband delivering his resignation speech. Tim Ireland/AP

The United Kingdom voted on May 7 to determine its next government. Despite predictions that there would be a hung parliament with an advantage to Labor in forming a coalition government, that did not turn out to be the case. Instead the Conservatives won an outright majority, meaning that David Cameron will continue as Prime Minister, not Labor Party leader Ed Miliband, as most believed.

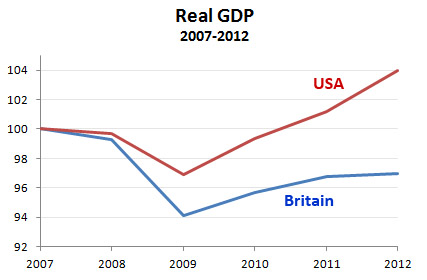

Naturally, Labor Party supporters, and progressives in general, are aghast at this outcome. And certainly a Labor government would have governed differently than the Tories, who have been ruling the UK since 2010 and have famously adopted budget austerity as their main economic policy. But how differently? Oddly, the ascension of “Red Ed”, as the British tabloid press likes to call him, may not have made as big a difference as one might think. This is because the Labor Party did not propose to break decisively from the pro-austerity policies of the Tory government. Indeed, the Labor Party election manifesto promised to “cut the deficit every year” regardless of the state of the economy.

This “Budget Responsibility Lock”, as the manifesto jauntily called it, may seem bonkers given everything we have learned about the negative economic effects of austerity policies since 2010, including in the UK, and the rapidly declining intellectual credibility of austerity as an economic doctrine. Well, that’s because it is bonkers, as Paul Krugman explains in a lengthy article for The Guardian with the somewhat despairing title: “The austerity delusion: The case for cuts was a lie—Why does Britain still believe it?“

The bulk of Krugman’s article is a detailed and very convincing analysis of how nutty austerity was as a policy and how poorly it has worked. However, I’m not sure he really clears up the question of why British economic discourse is still dominated by this mythology. But this is a tough one. And it’s not as if the British Labor Party is alone in its attempts to reconcile social democracy with austerity; most continental social democratic parties are having similar difficulties breaking out of the austerity framework.

In fact, the center left party that’s most ostentatiously stepped out of this framework is that wild-eyed band of Bolsheviks, the American Democratic Party, which has moved steadily away from deficit mania since 2011. This raises an interesting question. Given the macroeconomic straightjacket European social democrats seem determined to keep themselves in, is the Democratic Party really the torchbearer now for social democratic progress?

In this regard, it’s interesting to turn to a recent book by political scientist Lane Kenworthy, Social Democratic America, that makes the case (summarized here and here) that, over the long term, the US is, in fact, on a social democratic course.

By social democracy, Kenworthy means an economic system featuring “a commitment to the extensive use of government policy to promote economic security, expand opportunity, and ensure rising living standards for all… [I]t aims to do so while also safeguarding economic freedom, economic flexibility, and market dynamism, all of which have long been hallmarks of the U.S. economy.” He calls this “modern” social democracy, contrasting with “traditional” social democracy in that it goes beyond merely helping people survive without employment to also providing “services aimed at boosting employment and enhancing productivity: publicly funded child care and preschool, job-training and job-placement programs, significant infrastructure projects, and government support for private-sector research and development.”

Kenworthy anticipates that, as we move toward this kind of social democracy, we will do most of the following:

1) Increase the minimum wage and index it to inflation.

2) Increase the Earned Income Tax Credit while making it available to middle income families and indexing it to GDP per capita.

3) Increase benefit levels and loosen eligibility levels for Temporary Assistance for Needy Families, general assistance, food stamps, housing assistance, and energy assistance.

4) Mandate paid parental leave.

5) Expand access to unemployment insurance.

6) Increase the Child Care Tax Credit.

7) Universalize access to pre-K.

8) Institute a supplemental defined contribution plan with automatic enrollment.

9) Increase federal spending on public child care, roads and bridges, and health care; and mandate more holidays and vacation time for workers.

It’s interesting to note that most of this list is consistent with the mainstream policy commitments of the Democratic Party and that a good chunk of it will probably find its way into the platform of the 2016 Democratic Presidential candidate. Maybe Kenworthy’s prediction is not so far-fetched.

One other reason to see the US as a potential beacon for social democratic progress stems from the nature of political coalitions in an era of demographic change. In the United States, the Democratic Party has largely succeeded in capturing the current wave of modernizing demographic change (immigrants, minorities, professionals, seculars, unmarried women, the highly-educated, the Millennial generation, etc.) Emerging demographic groups generally favor the Democrats by wide margins, which combined with residual strength among traditional constituencies gives them a formidable electoral coalition. The challenge for American progressives is therefore mostly about keeping their demographically enhanced coalition together in the face of conservative attacks and getting it to turn out in midterm elections.

The situation is different in Europe, where modernizing demographic change has, so far, not done social democratic parties much good. One reason is that some of these demographic changes do not loom as large in most European countries as they do in the United States. The immigrant/minority population starts from a smaller base so the impact of growth, even where rapid, is more limited. And the younger generation, while progressive, does not have the population weight it does in America.

Beyond that, however, is a factor that has prevented social democrats from harnessing the still-considerable power of modernizing demographic change in Europe. That is the nature of European party systems. Unlike in the United States, where the center-left party, the Democrats, has no meaningful electoral competition for the progressive vote, European social democrats typically do have such competition and from three different parts of the political spectrum: greens; left socialists; and liberal centrists. And not only do they have competition, these other parties, on aggregate, typically overperform among emerging demographics, while social democrats generally underperform. Thus it would appear that social democrats, who have also hemmoraged support from traditional working class voters, will be increasingly unable to build viable progressive coalitions by themselves.

Bringing progressive constituencies together across parties is of course difficult to do and so far European social democrats seem completely at sea on how to handle this challenge. Much easier to have all those constituencies together in one party—like we do in the United States.

The road to progress isn’t clear anywhere but, defying national stereotypes, it’s starting to look a bit clearer in the US than in Europe.